Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – how we spend our days is how we spend our lives, the 4 people a great writer must be, Amiel on love and its demons, 20 years of subversive art experiments, and more – you can catch up here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – how we spend our days is how we spend our lives, the 4 people a great writer must be, Amiel on love and its demons, 20 years of subversive art experiments, and more – you can catch up here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

"That is the way to learn the most, that when you are doing something with such enjoyment that you don’t notice that the time passes."

With Father's Day around the corner, here comes a fine addition to history's greatest letters of fatherly advice from none other than Albert Einstein – brilliant physicist, proponent of peace, debater of science and spirituality, champion of kindness – who was no stranger to dispensing epistolary empowerment to young minds.

With Father's Day around the corner, here comes a fine addition to history's greatest letters of fatherly advice from none other than Albert Einstein – brilliant physicist, proponent of peace, debater of science and spirituality, champion of kindness – who was no stranger to dispensing epistolary empowerment to young minds.

In 1915, aged thirty-six, Einstein was living in wartorn Berlin, while his estranged wife, Mileva, and their two sons, Hans Albert Einstein and Eduard “Tete” Einstein, lived in comparatively safe Vienna. On November 4 of that year, having just completed the two-page masterpiece that would catapult him into international celebrity and historical glory, his theory of general relativity, Einstein sent 11-year-old Hans Albert the following letter, found in Posterity: Letters of Great Americans to Their Children (public library) – the same wonderful anthology that gave us some of history's greatest motherly advice, Benjamin Rush's wisdom on travel and life, and Sherwood Anderson's counsel on the creative life. Einstein, who takes palpable pride in his intellectual accomplishments, speaks to the rhythms of creative absorption as the fuel for the internal engine of learning:

My dear Albert,

My dear Albert,

Yesterday I received your dear letter and was very happy with it. I was already afraid you wouldn’t write to me at all any more. You told me when I was in Zurich, that it is awkward for you when I come to Zurich. Therefore I think it is better if we get together in a different place, where nobody will interfere with our comfort. I will in any case urge that each year we spend a whole month together, so that you see that you have a father who is fond of you and who loves you. You can also learn many good and beautiful things from me, something another cannot as easily offer you. What I have achieved through such a lot of strenuous work shall not only be there for strangers but especially for my own boys. These days I have completed one of the most beautiful works of my life, when you are bigger, I will tell you about it.

I am very pleased that you find joy with the piano. This and carpentry are in my opinion for your age the best pursuits, better even than school. Because those are things which fit a young person such as you very well. Mainly play the things on the piano which please you, even if the teacher does not assign those. That is the way to learn the most, that when you are doing something with such enjoyment that you don’t notice that the time passes. I am sometimes so wrapped up in my work that I forget about the noon meal. . . .

Be with Tete kissed by your

Papa.

Regards to Mama.

.

.

Complement with more timeless advice from famous dads, including Ted Hughes, Charles Dickens, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson, John Steinbeck, and much more wisdom found in Posterity.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"I do not accept subtractive models of love, only additive ones."

It's been said that "who we are and who we become depends, in part, on whom we love." But the opposite is also true – we blossom into who we are under the warming light of the love that surrounds us.

It's been said that "who we are and who we become depends, in part, on whom we love." But the opposite is also true – we blossom into who we are under the warming light of the love that surrounds us.

This beautiful osmosis is precisely what Andrew Solomon explores in Far From the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity (public library) – a fascinating and deeply moving meditation on our evolving definitions of family, our diverse dispositions toward parenthood, the enduring ideals of motherhood and fatherhood, and, perhaps above all, how the freedom of identity unites us in our differences.

"Nothing has a stronger influence psychologically on their environment, and especially on their children," legendary psychoanalyst Carl Jung famously asserted, "than the unlived lives of the parents." And, indeed, the propensity for projection in parents who want to see in their children better or unfulfilled versions of themselves, Solomon argues, is a dangerous byproduct of our selfish genes:

In the subconscious fantasies that make conception look so alluring, it is often ourselves that we would like to see live forever, not someone with a personality of his own. Having anticipated the onward march of our selfish genes, many of us are unprepared for children who present unfamiliar needs. Parenthood abruptly catapults us into a permanent relationship with a stranger, and the more alien the stranger, the stronger the whiff of negativity. We depend on the guarantee in our children’s faces that we will not die. Children whose defining quality annihilates that fantasy of immortality are a particular insult; we must love them for themselves, and not for the best of ourselves in them, and that is a great deal harder to do. Loving our own children is an exercise for the imagination. … [But] our children are not us: they carry throwback genes and recessive traits and are subject right from the start to environmental stimuli beyond our control. And yet we are our children; the reality of being a parent never leaves those who have braved the metamorphosis.

In the subconscious fantasies that make conception look so alluring, it is often ourselves that we would like to see live forever, not someone with a personality of his own. Having anticipated the onward march of our selfish genes, many of us are unprepared for children who present unfamiliar needs. Parenthood abruptly catapults us into a permanent relationship with a stranger, and the more alien the stranger, the stronger the whiff of negativity. We depend on the guarantee in our children’s faces that we will not die. Children whose defining quality annihilates that fantasy of immortality are a particular insult; we must love them for themselves, and not for the best of ourselves in them, and that is a great deal harder to do. Loving our own children is an exercise for the imagination. … [But] our children are not us: they carry throwback genes and recessive traits and are subject right from the start to environmental stimuli beyond our control. And yet we are our children; the reality of being a parent never leaves those who have braved the metamorphosis.

Solomon goes on to differentiate between vertical, or directly inherited, and horizontal, or independently divergent, identity:

Because of the transmission of identity from one generation to the next, most children share at least some traits with their parents. These are vertical identities. Attributes and values are passed down from parent to child across the generations not only through strands of DNA, but also through shared cultural norms. Ethnicity, for example, is a vertical identity. Children of color are in general born to parents of color; the genetic fact of skin pigmentation is transmitted across generations along with a self-image as a person of color, even though that self-image may be subject to generational flux. Language is usually vertical, since most people who speak Greek raise their children to speak Greek, too, even if they inflect it differently or speak another language much of the time. Religion is moderately vertical: Catholic parents will tend to bring up Catholic children, though the children may turn irreligious or convert to another faith. Nationality is vertical, except for immigrants. Blondness and myopia are often transmitted from parent to child, but in most cases do not form a significant basis for identity— blondness because it is fairly insignificant, and myopia because it is easily corrected.

Because of the transmission of identity from one generation to the next, most children share at least some traits with their parents. These are vertical identities. Attributes and values are passed down from parent to child across the generations not only through strands of DNA, but also through shared cultural norms. Ethnicity, for example, is a vertical identity. Children of color are in general born to parents of color; the genetic fact of skin pigmentation is transmitted across generations along with a self-image as a person of color, even though that self-image may be subject to generational flux. Language is usually vertical, since most people who speak Greek raise their children to speak Greek, too, even if they inflect it differently or speak another language much of the time. Religion is moderately vertical: Catholic parents will tend to bring up Catholic children, though the children may turn irreligious or convert to another faith. Nationality is vertical, except for immigrants. Blondness and myopia are often transmitted from parent to child, but in most cases do not form a significant basis for identity— blondness because it is fairly insignificant, and myopia because it is easily corrected.

Often, however, someone has an inherent or acquired trait that is foreign to his or her parents and must therefore acquire identity from a peer group. This is a horizontal identity. Such horizontal identities may reflect recessive genes, random mutations, prenatal influences, or values and preferences that a child does not share with his progenitors. Being gay is a horizontal identity; most gay kids are born to straight parents, and while their sexuality is not determined by their peers, they learn gay identity by observing and participating in a subculture outside the family. Physical disability tends to be horizontal, as does genius. Psychopathy, too, is often horizontal; most criminals are not raised by mobsters and must invent their own treachery. So are conditions such as autism and intellectual disability.

But Solomon wasn't moved to consider these intricate issues until he had first-hand contact with a particular horizontal identity other than his own. In 1993, he was assigned to do a story on Deaf culture for The New York Times and immersed himself in the Deaf world – a world in which most deaf children are born to hearing parents, who often wish their children had full-range hearing and led "normal" lives. And yet he found himself in awe of the vibrant richness of Deaf identity as he visited Deaf theater performances, reading clubs, and beauty pageants.

Shortly thereafter, a friend of Solomon's had a daughter diagnosed with dwarfism and "wondered whether she should bring up her daughter to consider herself just like everyone else, only shorter [or] whether she should make sure her daughter had dwarf role models." Suddenly, a pattern revealed itself – a tendency for "normal" culture, including the parents of children with different horizontal identities, to try to subvert or even "cure" those identities – and it rang with painful familiarity for Solomon, who is himself gay. He writes:

I had been startled to note my common ground with the Deaf, and now I was identifying with a dwarf; I wondered who else was out there waiting to join our gladsome throng. I thought that if gayness, an identity, could grow out of homosexuality, an illness, and Deafness, an identity, could grow out of deafness, an illness, and if dwarfism as an identity could emerge from an apparent disability, then there must be many other categories in this awkward interstitial territory. It was a radicalizing insight. Having always imagined myself in a fairly slim minority, I suddenly saw that I was in a vast company. Difference unites us. While each of these experiences can isolate those who are affected, together they compose an aggregate of millions whose struggles connect them profoundly. The exceptional is ubiquitous; to be entirely typical is the rare and lonely state.

I had been startled to note my common ground with the Deaf, and now I was identifying with a dwarf; I wondered who else was out there waiting to join our gladsome throng. I thought that if gayness, an identity, could grow out of homosexuality, an illness, and Deafness, an identity, could grow out of deafness, an illness, and if dwarfism as an identity could emerge from an apparent disability, then there must be many other categories in this awkward interstitial territory. It was a radicalizing insight. Having always imagined myself in a fairly slim minority, I suddenly saw that I was in a vast company. Difference unites us. While each of these experiences can isolate those who are affected, together they compose an aggregate of millions whose struggles connect them profoundly. The exceptional is ubiquitous; to be entirely typical is the rare and lonely state.

But in families, Solomon argues, many parents tend to perceive their child's horizontal identity as not only a problem to be fixed but a personal failure or even an affront. He observes:

Whereas families tend to reinforce vertical identities from earliest childhood, many will oppose horizontal ones. Vertical identities are usually respected as identities; horizontal ones are often treated as flaws.

Whereas families tend to reinforce vertical identities from earliest childhood, many will oppose horizontal ones. Vertical identities are usually respected as identities; horizontal ones are often treated as flaws.

One could argue that black people face many disadvantages in the United States today, but there is little research into how gene expression could be altered to make the next generation of children born to black parents come out with straight, flaxen hair and creamy complexions. In modern America, it is sometimes hard to be Asian or Jewish or female, yet no one suggests that Asians, Jews, or women would be foolish not to become white Christian men if they could. Many vertical identities make people uncomfortable, and yet we do not attempt to homogenize them. The disadvantages of being gay are arguably no greater than those of such vertical identities, but most parents have long sought to turn their gay children straight. … Labeling a child’s mind as diseased – whether with autism, intellectual disabilities, or transgenderism – may reflect the discomfort that mind gives parents more than any discomfort it causes their child.

As we've observed the powerful role of language in other cultural change and social justice reform movements, the way we talk about these issues not only reflects but also shapes the way we think about them. Solomon calls for a necessary change in vocabulary by way of an apt analogy:

We often use illness to disparage a way of being, and identity to validate that same way of being. This is a false dichotomy. In physics, the Copenhagen interpretation defines energy/ matter as behaving sometimes like a wave and sometimes like a particle, which suggests that it is both, and posits that it is our human limitation to be unable to see both at the same time. The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Paul Dirac identified how light appears to be a particle if we ask a particle-like question, and a wave if we ask a wavelike question. A similar duality obtains in this matter of self. Many conditions are both illness and identity, but we can see one only when we obscure the other. Identity politics refutes the idea of illness, while medicine shortchanges identity. Both are diminished by this narrowness.

We often use illness to disparage a way of being, and identity to validate that same way of being. This is a false dichotomy. In physics, the Copenhagen interpretation defines energy/ matter as behaving sometimes like a wave and sometimes like a particle, which suggests that it is both, and posits that it is our human limitation to be unable to see both at the same time. The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Paul Dirac identified how light appears to be a particle if we ask a particle-like question, and a wave if we ask a wavelike question. A similar duality obtains in this matter of self. Many conditions are both illness and identity, but we can see one only when we obscure the other. Identity politics refutes the idea of illness, while medicine shortchanges identity. Both are diminished by this narrowness.

Physicists gain certain insights from understanding energy as a wave, and other insights from understanding it as a particle, and use quantum mechanics to reconcile the information they have gleaned. Similarly, we have to examine illness and identity, understand that observation will usually happen in one domain or the other, and come up with a syncretic mechanics. We need a vocabulary in which the two concepts are not opposites, but compatible aspects of a condition. The problem is to change how we assess the value of individuals and of lives, to reach for a more ecumenical take on healthy.

Having a child with a horizontal identity vastly different from that of the parent, Solomon argues, is a kind of magnifying mirror for the parent's character and capacity as a human being:

Having exceptional children exaggerates parental tendencies; those who would be bad parents become awful parents, but those who would be good parents often become extraordinary.

Having exceptional children exaggerates parental tendencies; those who would be bad parents become awful parents, but those who would be good parents often become extraordinary.

But the dynamic flows both ways:

Parents’ early responses to and interactions with a child determine how that child comes to view himself. These parents are also profoundly changed by their experiences.

Parents’ early responses to and interactions with a child determine how that child comes to view himself. These parents are also profoundly changed by their experiences.

"Love can change a person," Lemony Snicket wrote in Horseradish: Bitter Truths You Can’t Avoid, "the way a parent can change a baby – awkwardly, and often with a great deal of mess." But Solomon makes a case for precisely the inverse – that a child can change a parent, just as awkwardly and with just as much of a mess, through the power of love:

Self-acceptance is part of the ideal, but without familial and societal acceptance, it cannot ameliorate the relentless injustices to which many horizontal identity groups are subject and will not bring about adequate reform. … To look deep into your child’s eyes and see in him both yourself and something utterly strange, and then to develop a zealous attachment to every aspect of him, is to achieve parenthood’s self-regarding, yet unselfish, abandon. It is astonishing how often such mutuality has been realized – how frequently parents who had supposed that they couldn’t care for an exceptional child discover that they can. The parental predisposition to love prevails in the most harrowing of circumstances. There is more imagination in the world than one might think.

Self-acceptance is part of the ideal, but without familial and societal acceptance, it cannot ameliorate the relentless injustices to which many horizontal identity groups are subject and will not bring about adequate reform. … To look deep into your child’s eyes and see in him both yourself and something utterly strange, and then to develop a zealous attachment to every aspect of him, is to achieve parenthood’s self-regarding, yet unselfish, abandon. It is astonishing how often such mutuality has been realized – how frequently parents who had supposed that they couldn’t care for an exceptional child discover that they can. The parental predisposition to love prevails in the most harrowing of circumstances. There is more imagination in the world than one might think.

What Solomon's key point boils down to is a necessary and thoughtful addition to history's most notable definitions of love. In the closing pages, he writes:

Some people are trapped by the belief that love comes in finite quantities, and that our kind of love exhausts the supply upon which they need to draw. I do not accept competitive models of love, only additive ones. My journey toward a family and this book have taught me that love is a magnifying phenomenon – that every increase in love strengthens all the other love in the world. . . .

Some people are trapped by the belief that love comes in finite quantities, and that our kind of love exhausts the supply upon which they need to draw. I do not accept competitive models of love, only additive ones. My journey toward a family and this book have taught me that love is a magnifying phenomenon – that every increase in love strengthens all the other love in the world. . . .

In his stirring TED talk, Solomon paraphrases this already poignant sentiment even more beautifully:

I do not accept subtractive models of love, only additive ones.

I do not accept subtractive models of love, only additive ones.

Far From the Tree comes a decade after Solomon's indispensable The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression.

:: WATCH / SHARE ::

The rare talents of trust, gusto, and guts under pressure.

Long before the listicle epidemic of the social web, 11th-century Japanese courtesan Sei Shanagon, the world's first "blogger," enumerated 7 rare things in life, beloved novelist Umberto Eco asserted the list was the origin of culture, and the inimitable Susan Sontag reflected on why lists appeal to us.

Long before the listicle epidemic of the social web, 11th-century Japanese courtesan Sei Shanagon, the world's first "blogger," enumerated 7 rare things in life, beloved novelist Umberto Eco asserted the list was the origin of culture, and the inimitable Susan Sontag reflected on why lists appeal to us.

One of modern history's most fierce list-lovers is advertising legend and original "Mad Man" David Ogilvy, as evidenced by his enduring 10 no-bullshit tips on writing. From The Unpublished David Ogilvy (public library) – which also gave us Ogilvy's endearing note to a veteran copywriter – comes his list of the ten qualities he looks for in creative leaders, as originally delivered in one of Ogilvy's eloquent talks to the staff. Among expected necessities like work ethic and the ability to transcend fear in the creative process are also a few oft-overlooked but equally important requirements like a healthy dose of nuttiness and comedic sensitivity. (We already know that humor and creativity are driven by the same mechanics.)

- High standards of personal ethics.

- Big people, without pettiness.

- Guts under pressure, resilience in defeat.

- Brilliant brains – not safe plodders.

- A capacity for hard work and midnight oil.

- Charisma – charm and persuasiveness.

- A streak of unorthodoxy – creative innovators.

- The courage to make tough decisions.

- Inspiring enthusiasts – with trust and gusto.

- A sense of humor.

The Unpublished David Ogilvy features many more of Ogilvy's lists, as well as a wealth of his insights on everything from creativity to management to the nitty-gritty of the communication arts.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both."

The friction between science and religion stretches from Galileo's famous letter to today's leading thinkers. And yet we're seeing that, for all its capacity for ignorance, religion might have some valuable lessons for secular thought and the two need not be regarded as opposites.

The friction between science and religion stretches from Galileo's famous letter to today's leading thinkers. And yet we're seeing that, for all its capacity for ignorance, religion might have some valuable lessons for secular thought and the two need not be regarded as opposites.

In 1996, mere months before his death, the great Carl Sagan – cosmic sage, voracious reader, hopeless romantic – explored the relationship between the scientific and the spiritual in The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (public library). He writes:

Plainly there is no way back. Like it or not, we are stuck with science. We had better make the best of it. When we finally come to terms with it and fully recognize its beauty and its power, we will find, in spiritual as well as in practical matters, that we have made a bargain strongly in our favor.

Plainly there is no way back. Like it or not, we are stuck with science. We had better make the best of it. When we finally come to terms with it and fully recognize its beauty and its power, we will find, in spiritual as well as in practical matters, that we have made a bargain strongly in our favor.

But superstition and pseudoscience keep getting in the way, distracting us, providing easy answers, dodging skeptical scrutiny, casually pressing our awe buttons and cheapening the experience, making us routine and comfortable practitioners as well as victims of credulity.

And yet science, Sagan argues, isn't diametrically opposed to spirituality. He echoes Ptolemy's timeless awe at the cosmos and reflects on what Richard Dawkins has called the magic of reality, noting the intense spiritual elevation that science is capable of producing:

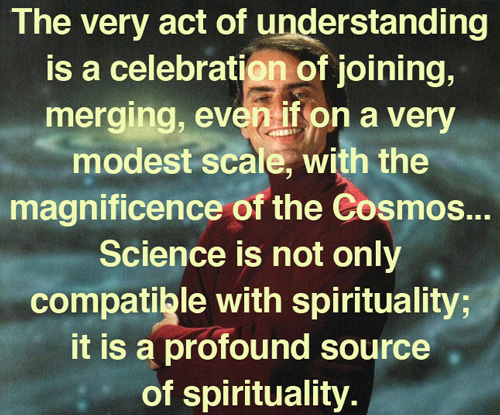

In its encounter with Nature, science invariably elicits a sense of reverence and awe. The very act of understanding is a celebration of joining, merging, even if on a very modest scale, with the magnificence of the Cosmos. And the cumulative worldwide build-up of knowledge over time converts science into something only a little short of a trans-national, trans-generational meta-mind.

In its encounter with Nature, science invariably elicits a sense of reverence and awe. The very act of understanding is a celebration of joining, merging, even if on a very modest scale, with the magnificence of the Cosmos. And the cumulative worldwide build-up of knowledge over time converts science into something only a little short of a trans-national, trans-generational meta-mind.

“Spirit” comes from the Latin word “to breathe.” What we breathe is air, which is certainly matter, however thin. Despite usage to the contrary, there is no necessary implication in the word “spiritual” that we are talking of anything other than matter (including the matter of which the brain is made), or anything outside the realm of science. On occasion, I will feel free to use the word. Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual. So are our emotions in the presence of great art or music or literature, or of acts of exemplary selfless courage such as those of Mohandas Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr. The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both.

Reminding us once again of his timeless wisdom on the vital balance between skepticism and openness and the importance of evidence, Sagan goes on to juxtapose the accuracy of science with the unfounded prophecies of religion:

Not every branch of science can foretell the future – paleontology can’t – but many can and with stunning accuracy. If you want to know when the next eclipse of the Sun will be, you might try magicians or mystics, but you’ll do much better with scientists. They will tell you where on Earth to stand, when you have to be there, and whether it will be a partial eclipse, a total eclipse, or an annular eclipse. They can routinely predict a solar eclipse, to the minute, a millennium in advance. You can go to the witch doctor to lift the spell that causes your pernicious anaemia, or you can take vitamin Bl2. If you want to save your child from polio, you can pray or you can inoculate. If you’re interested in the sex of your unborn child, you can consult plumb-bob danglers all you want (left-right, a boy; forward-back, a girl – or maybe it’s the other way around), but they’ll be right, on average, only one time in two. If you want real accuracy (here, 99 per cent accuracy), try amniocentesis and sonograms. Try science.

Not every branch of science can foretell the future – paleontology can’t – but many can and with stunning accuracy. If you want to know when the next eclipse of the Sun will be, you might try magicians or mystics, but you’ll do much better with scientists. They will tell you where on Earth to stand, when you have to be there, and whether it will be a partial eclipse, a total eclipse, or an annular eclipse. They can routinely predict a solar eclipse, to the minute, a millennium in advance. You can go to the witch doctor to lift the spell that causes your pernicious anaemia, or you can take vitamin Bl2. If you want to save your child from polio, you can pray or you can inoculate. If you’re interested in the sex of your unborn child, you can consult plumb-bob danglers all you want (left-right, a boy; forward-back, a girl – or maybe it’s the other way around), but they’ll be right, on average, only one time in two. If you want real accuracy (here, 99 per cent accuracy), try amniocentesis and sonograms. Try science.

Think of how many religions attempt to validate themselves with prophecy. Think of how many people rely on these prophecies, however vague, however unfulfilled, to support or prop up their beliefs. Yet has there ever been a religion with the prophetic accuracy and reliability of science? There isn’t a religion on the planet that doesn’t long for a comparable ability – precise, and repeatedly demonstrated before committed skeptics – to foretell future events. No other human institution comes close.

Nearly two decades after The Demon-Haunted World, Sagan's son, Dorion, made a similar and similarly eloquent case for why science and philosophy need each other. Complement it with this meditation on science vs. scripture and the difference between curiosity and wonder.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"We are people, there is no doubt, who exist solely insofar as we write, otherwise we don’t exist at all."

Culled from the 600+ pages of Italo Calvino: Letters, 1941-1985 (public library) – the same fantastic recently released tome that gave us Calvino's prescient meditation on abortion and the meaning of life – are the beloved author's collected insights on writing spanning more than four decades of his career, a fine addition to this master list of famous writers' wisdom on the craft.

Culled from the 600+ pages of Italo Calvino: Letters, 1941-1985 (public library) – the same fantastic recently released tome that gave us Calvino's prescient meditation on abortion and the meaning of life – are the beloved author's collected insights on writing spanning more than four decades of his career, a fine addition to this master list of famous writers' wisdom on the craft.

On March 7, 1942, writing from university to his best friend and literary-minded comrade-in-arms, Eugenio Scalfari, in the typical tone of irreverent facetiousness the two shared, 18-year-old Calvino extols the joy and art of writing letters::

A fine thing it is to have a distant friend who writes long letters full of drivel and to be able to reply to him with equally lengthy letters full of drivel; fine not because I like to plunge into captious polemics nor because I enjoy getting certain ideas into the head of some idiot from the Urbe, but because writing long letters to friends means having a moral excuse for not studying.

A fine thing it is to have a distant friend who writes long letters full of drivel and to be able to reply to him with equally lengthy letters full of drivel; fine not because I like to plunge into captious polemics nor because I enjoy getting certain ideas into the head of some idiot from the Urbe, but because writing long letters to friends means having a moral excuse for not studying.

In the same letter, Calvino admonishes Eugenio about the mixed motives of the publishing world – at least as an 18-year-old aspiring writer saw it:

Don’t trust the big names that support youth movements: it’s fashionable to show you’re favoring youth.

Don’t trust the big names that support youth movements: it’s fashionable to show you’re favoring youth.

Several weeks later, Calvino – who had gone to university to study agriculture but found himself increasingly drawn to literature as he immersed himself in the dullness of his major – shares with Eugenio an intense expression of the inner contradiction that defines being human, the increasing inner tug-of-war between the disinterested agronomist and self-conscious poet:

It will perhaps please you to know that, as regards the famous italcalvinian dualism, the agronomist is about to lose out, and the poet will emerge as the clear winner. My revision for the exams is still today in a deplorable state and offers no hope of recovery. The Easter holidays, which were filled with the pleasures of cheerful cycling trips along the Via Aurelia and daring but unsuccessful pursuits of Riviera Amazons, have long disappeared. The poet, on the other hand, has been more productive: he has finished the famous Brezza di terra (Land Breeze) and would now do well to go off and hide. The work is solemn rubbish and I don’t think I’ll have the courage to present it, not even in Florence. Rhetoric, artifice, and trite Pirandellian ideas grafted onto pompous D’Annunzian language. But also daring, warmth, enthusiasm and, what counts above all, real poetry.

It will perhaps please you to know that, as regards the famous italcalvinian dualism, the agronomist is about to lose out, and the poet will emerge as the clear winner. My revision for the exams is still today in a deplorable state and offers no hope of recovery. The Easter holidays, which were filled with the pleasures of cheerful cycling trips along the Via Aurelia and daring but unsuccessful pursuits of Riviera Amazons, have long disappeared. The poet, on the other hand, has been more productive: he has finished the famous Brezza di terra (Land Breeze) and would now do well to go off and hide. The work is solemn rubbish and I don’t think I’ll have the courage to present it, not even in Florence. Rhetoric, artifice, and trite Pirandellian ideas grafted onto pompous D’Annunzian language. But also daring, warmth, enthusiasm and, what counts above all, real poetry.

In early May of 1942, after Eugenio sends Italo one of his poems, Calvino echoes Wordsworth as he articulates his budding philosophy on poetry, then trails off in a meta-affirmation:

I’ve read your poem. I too, if you remember, wrote a Hermetic poem in my early youth. I know that gives enormous satisfaction to the person who writes it. But whether the person who reads it shares this enthusiasm is another matter. It’s too subjective, Hermeticism, do you see? And I see art as communication. The poet turns in on himself, tries to pin down what he has seen and felt, then pulls it out so that others can understand it. But I can’t understand these things: these discourses about the ego and the non-ego I leave to you. Yes, I understand, there’s the struggle to express the inexpressible, typical of modern art, and these are all fine things, but I …

I’ve read your poem. I too, if you remember, wrote a Hermetic poem in my early youth. I know that gives enormous satisfaction to the person who writes it. But whether the person who reads it shares this enthusiasm is another matter. It’s too subjective, Hermeticism, do you see? And I see art as communication. The poet turns in on himself, tries to pin down what he has seen and felt, then pulls it out so that others can understand it. But I can’t understand these things: these discourses about the ego and the non-ego I leave to you. Yes, I understand, there’s the struggle to express the inexpressible, typical of modern art, and these are all fine things, but I …

Later in the same lengthy letter, Calvino, sharing in Bukowski's assertion that writing should come "unasked out of your heart and your mind and your mouth and your gut" and dissenting from Coleridge's view that "the mere addition of meter does not in itself entitle a work to the name of poem," engages in his usual self-derisive conviction:

I’m a regular guy, I like well-defined outlines, I’m old-fashioned, bourgeois. My stories are full of facts, they have a beginning and an end. For that reason they will never be able to find success with the critics, nor occupy a place in contemporary literature. I write poetry when I have a thought that I absolutely have to bring out, I write to give vent to my feelings and I write using rhyme because I like it, tum-tetum tumtetum tum te-tum, because I’ve got no ear, and poetry without rhyme or meter seems like soup without salt, and I write (mock me, you crowds! Make me a figure of public scorn!) I write … sonnets … and writing sonnets is boring, you have to find rhymes, you have to write hendecasyllables so after a while I get bored and my drawer is overflowing with unfinished short poems.

I’m a regular guy, I like well-defined outlines, I’m old-fashioned, bourgeois. My stories are full of facts, they have a beginning and an end. For that reason they will never be able to find success with the critics, nor occupy a place in contemporary literature. I write poetry when I have a thought that I absolutely have to bring out, I write to give vent to my feelings and I write using rhyme because I like it, tum-tetum tumtetum tum te-tum, because I’ve got no ear, and poetry without rhyme or meter seems like soup without salt, and I write (mock me, you crowds! Make me a figure of public scorn!) I write … sonnets … and writing sonnets is boring, you have to find rhymes, you have to write hendecasyllables so after a while I get bored and my drawer is overflowing with unfinished short poems.

In July of the following year, still in school and approaching his 20th birthday, Italo grumbles to Eugenio in frustration over his creative process, which seems to disobey the general principles of intuitive incubation and unconscious processing:

I’m still too ignorant to write articles and as for my output of short stories, a famous summer of overproduction has been followed by years of crisis. … All the ideas currently in my head are subject to a strange phenomenon: while I work on them and perfect them continuously from the philosophical point of view, they stay rudimentary and barely sketched on the dramatic and artistic side. In my creativity thought has the upper hand over imagination.

I’m still too ignorant to write articles and as for my output of short stories, a famous summer of overproduction has been followed by years of crisis. … All the ideas currently in my head are subject to a strange phenomenon: while I work on them and perfect them continuously from the philosophical point of view, they stay rudimentary and barely sketched on the dramatic and artistic side. In my creativity thought has the upper hand over imagination.

Having long left school and working on his second novel, Calvino found himself no less full of inner contradiction and resistance to the calling of the writing life and its grueling routines. In a November 1948 to his friend Silvio Micheli, he voices, as if in a desperate effort to reconcile, his conflicted desires :

When you’re working you get buried, drowned under things. You’ve no more friends nor art. Only when you’ve an evening or afternoon free can you roam the streets or court a girl. That’s all. In short, working is pointless. I mean, from the point of view of education. But it’s essential. I cannot – and I don’t want to – live the writer’s life, that is to say write for a living. The novel I was writing, which for months and months had sucked all my blood (because, stubborn as I am, I was determined to finish it even though I no longer felt it was going anywhere), is dead, awful, full of wonderful clever things but desperately bad, forced, it’ll never work and I must not finish it. And I must not write for some time now otherwise I’d make more mistakes. I hope that Einaudi will publish my short stories eventually, they’re the only thing I believe in and which I believe are useful.

When you’re working you get buried, drowned under things. You’ve no more friends nor art. Only when you’ve an evening or afternoon free can you roam the streets or court a girl. That’s all. In short, working is pointless. I mean, from the point of view of education. But it’s essential. I cannot – and I don’t want to – live the writer’s life, that is to say write for a living. The novel I was writing, which for months and months had sucked all my blood (because, stubborn as I am, I was determined to finish it even though I no longer felt it was going anywhere), is dead, awful, full of wonderful clever things but desperately bad, forced, it’ll never work and I must not finish it. And I must not write for some time now otherwise I’d make more mistakes. I hope that Einaudi will publish my short stories eventually, they’re the only thing I believe in and which I believe are useful.

A few weeks prior, Calvino had written to another friend:

For seven or eight months now I’ve been mucking about with a novel that I began in a moment of weakness and it’s turning out to be very bad, causing me to waste lots of my time. But at least it’ll get rid of my desire to write novels for four or five years, which is what I dream of doing, and will allow me to study kind of seriously and learn to write decently.

For seven or eight months now I’ve been mucking about with a novel that I began in a moment of weakness and it’s turning out to be very bad, causing me to waste lots of my time. But at least it’ll get rid of my desire to write novels for four or five years, which is what I dream of doing, and will allow me to study kind of seriously and learn to write decently.

On July 27, 1949, Calvino writes to Cesare Pavese:

To write well about the elegant world you have to know it and experience it to the depths of your being just as Proust, Radiguet and Fitzgerald did: what matters is not whether you love it or hate it, but only to be quite clear about your position regarding it.

To write well about the elegant world you have to know it and experience it to the depths of your being just as Proust, Radiguet and Fitzgerald did: what matters is not whether you love it or hate it, but only to be quite clear about your position regarding it.

Calvino echoes Herbert Spencer's admonition that "to have a specific style is to be poor in speech" in a March 1950 letter to Elsa Morante, one of the most influential postwar novelists, whom he had befriended:

The fact is that I already feel I am a prisoner of a kind of style and it is essential that I escape from it at all costs: I’m now trying to write a totally different book, but it’s damned difficult; I’m trying to break up the rhythms, the echoes which I feel the sentences I write eventually slide into, as into pre-existing molds, I try to see facts and things and people in the round instead of being drawn in colors that have no shading. For that reason the book I’m going to write interests me infinitely more than the other one.

The fact is that I already feel I am a prisoner of a kind of style and it is essential that I escape from it at all costs: I’m now trying to write a totally different book, but it’s damned difficult; I’m trying to break up the rhythms, the echoes which I feel the sentences I write eventually slide into, as into pre-existing molds, I try to see facts and things and people in the round instead of being drawn in colors that have no shading. For that reason the book I’m going to write interests me infinitely more than the other one.

As dangerous as the blind adhesion to a style, Calvino writes in a May 1959 letter, is the blind reliance on tools, the cult of medium over message – but harnessing the power of tools is one of the craft's greatest arts:

One should never have taboos about the tools we use, that as long as the thought or images or style one wants to put forward do not become deformed by the medium, one must on the contrary try to make use of the most powerful and most efficient of those tools.

One should never have taboos about the tools we use, that as long as the thought or images or style one wants to put forward do not become deformed by the medium, one must on the contrary try to make use of the most powerful and most efficient of those tools.

The creative process, however, is an entirely different matter for Calvino, one where efficiency and merit aren't necessarily correlated. In August of the same year, he complains to his friend Luigi Santucci about his creative block and sluggish daily routine – and yet he accepts that state, resigns to it as a given of the writing life. Above all, he adds to other famous meditations on why writers write – including ones from George Orwell, David Foster Wallace, Joan Didion, Mary Karr, Isabel Allende, Susan Orlean, Joy Williams, and Charles Bukowski – and speaks to the difference between a career and a calling, that profound and unshakable sense of purpose that is the mark of good art:

You can imagine how slowly my fictional output has been going this summer, you who know how much labor, dissatisfaction, irritability, uncertainty this work costs … However – and this is the point – it is worth it. Or rather: one does not ask if it’s worth it. We are people, there is no doubt, who exist solely insofar as we write, otherwise we don’t exist at all. Even if we did not have a single reader any more, we would have to write; and this not because ours can be a solitary job, on the contrary it is a dialog we take part in when we write, a common discourse, but this dialog can still always be supposed to be taking place with authors of the past, with authors we love and whose discourse we are forcing ourselves to develop, or else with those still to come, those we want through our writing to configure in one particular way rather than another. I am exaggerating: heaven help those who write without being read; for that reason there are too many people writing today and one cannot ask for indulgence for someone who has little to say, and one cannot allow trade-union or corporate sympathies.

You can imagine how slowly my fictional output has been going this summer, you who know how much labor, dissatisfaction, irritability, uncertainty this work costs … However – and this is the point – it is worth it. Or rather: one does not ask if it’s worth it. We are people, there is no doubt, who exist solely insofar as we write, otherwise we don’t exist at all. Even if we did not have a single reader any more, we would have to write; and this not because ours can be a solitary job, on the contrary it is a dialog we take part in when we write, a common discourse, but this dialog can still always be supposed to be taking place with authors of the past, with authors we love and whose discourse we are forcing ourselves to develop, or else with those still to come, those we want through our writing to configure in one particular way rather than another. I am exaggerating: heaven help those who write without being read; for that reason there are too many people writing today and one cannot ask for indulgence for someone who has little to say, and one cannot allow trade-union or corporate sympathies.

In a letter from early 1968, Calvino recognizes the writer's mind – like that of any great thinker – needs to be a cross-disciplinary one:

Every field of writing cannot be indifferent to other fields.

Every field of writing cannot be indifferent to other fields.

Much like H.P. Lovecraft argued against the distinction between "amateur" and "professional" journalists and Greil Marcus negated the divide between "high" and "low" culture, Calvino admonishes against the toxic dichotomy between "major" and "minor" writers and echoes Anaïs Nin's defense of the fluid self":

As a young man my aspiration was to become a “minor writer.” (Because it was always those that are called “minor” that I liked most and to whom I felt closest.) But this was already a flawed criterion because it presupposes that “major” writers exist. Basically, I am convinced that not only are there no “major” or “minor” writers, but writers themselves do not exist – or at least they do not count for much. As far as I am concerned, you still try too hard to explain Calvino with Calvino, to chart a history, a continuity in Calvino, and maybe this Calvino does not have any continuity, he dies and is reborn every second. What counts is whether in the work that he is doing at a certain point there is something that can relate to the present or future work done by others, as can happen to anyone who works, just because of the fact that they are creating such possibilities.

As a young man my aspiration was to become a “minor writer.” (Because it was always those that are called “minor” that I liked most and to whom I felt closest.) But this was already a flawed criterion because it presupposes that “major” writers exist. Basically, I am convinced that not only are there no “major” or “minor” writers, but writers themselves do not exist – or at least they do not count for much. As far as I am concerned, you still try too hard to explain Calvino with Calvino, to chart a history, a continuity in Calvino, and maybe this Calvino does not have any continuity, he dies and is reborn every second. What counts is whether in the work that he is doing at a certain point there is something that can relate to the present or future work done by others, as can happen to anyone who works, just because of the fact that they are creating such possibilities.

:: READ FULL ARTICLE / SHARE ::