Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – the best psychology, philosophy, art, and design books of the year, why the avocado should be extinct, Lou Reed's graphic-novel adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe, and more – you can catch up here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – the best psychology, philosophy, art, and design books of the year, why the avocado should be extinct, Lou Reed's graphic-novel adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe, and more – you can catch up here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

"It is an error … to think of children as a special kind of creature, almost a different race, rather than as normal, if immature, members of a particular family, and of the human family at large," J. R. R. Tolkien wrote in his superb meditation on fantasy and why there's no such thing as writing "for children," intimating that books able to captivate children's imagination aren't "children's books" but simply really good books. After the year's best books in psychology and philosophy, art and design, and history and biography, the season's subjective selection of best-of reading lists continue with the loveliest "children's" and picture-books of 2013. (Because the best children's books are, as Tolkien believes, always ones of timeless delight, do catch up on the selections for 2012, 2011, and 2010.)

"It is an error … to think of children as a special kind of creature, almost a different race, rather than as normal, if immature, members of a particular family, and of the human family at large," J. R. R. Tolkien wrote in his superb meditation on fantasy and why there's no such thing as writing "for children," intimating that books able to captivate children's imagination aren't "children's books" but simply really good books. After the year's best books in psychology and philosophy, art and design, and history and biography, the season's subjective selection of best-of reading lists continue with the loveliest "children's" and picture-books of 2013. (Because the best children's books are, as Tolkien believes, always ones of timeless delight, do catch up on the selections for 2012, 2011, and 2010.)

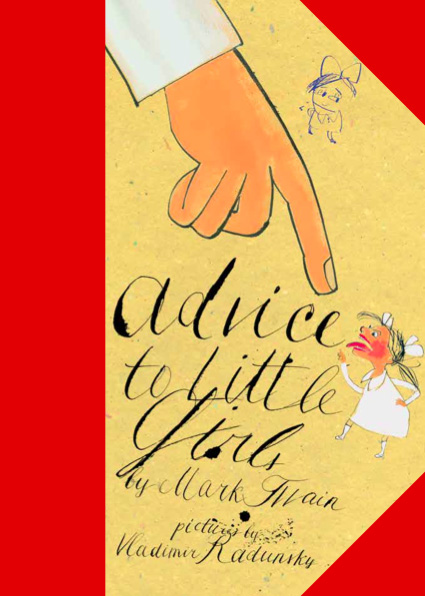

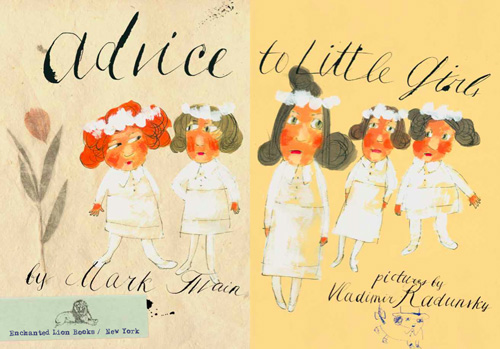

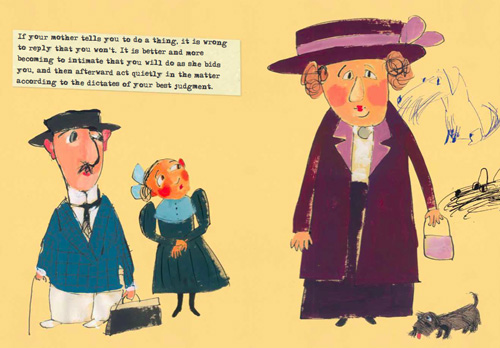

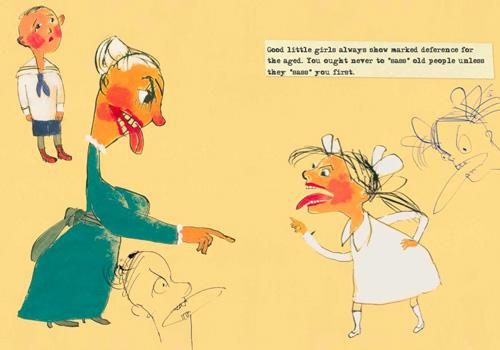

1. ADVICE TO LITTLE GIRLS

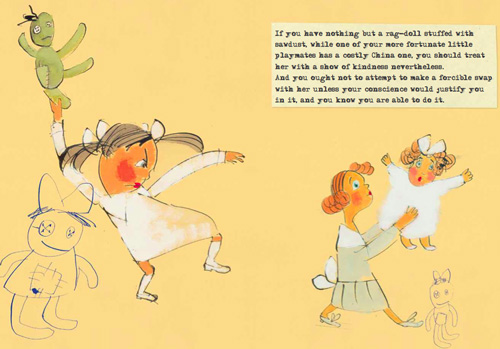

In 1865, when he was only thirty, Mark Twain penned a playful short story mischievously encouraging girls to think independently rather than blindly obey rules and social mores. In the summer of 2011, I chanced upon and fell in love with a lovely Italian edition of this little-known gem with Victorian-scrapbook-inspired artwork by celebrated Russian-born children's book illustrator Vladimir Radunsky. I knew the book had to come to life in English, so I partnered with the wonderful Claudia Zoe Bedrick of Brooklyn-based indie publishing house Enchanted Lion, maker of extraordinarily beautiful picture-books, and we spent the next two years bringing Advice to Little Girls (public library) to life in America – a true labor-of-love project full of so much delight for readers of all ages. (And how joyous to learn that it was also selected among NPR's best books of 2013!)

In 1865, when he was only thirty, Mark Twain penned a playful short story mischievously encouraging girls to think independently rather than blindly obey rules and social mores. In the summer of 2011, I chanced upon and fell in love with a lovely Italian edition of this little-known gem with Victorian-scrapbook-inspired artwork by celebrated Russian-born children's book illustrator Vladimir Radunsky. I knew the book had to come to life in English, so I partnered with the wonderful Claudia Zoe Bedrick of Brooklyn-based indie publishing house Enchanted Lion, maker of extraordinarily beautiful picture-books, and we spent the next two years bringing Advice to Little Girls (public library) to life in America – a true labor-of-love project full of so much delight for readers of all ages. (And how joyous to learn that it was also selected among NPR's best books of 2013!)

While frolicsome in tone and full of wink, the story is colored with subtle hues of grown-up philosophy on the human condition, exploring all the deft ways in which we creatively rationalize our wrongdoing and reconcile the good and evil we each embody.

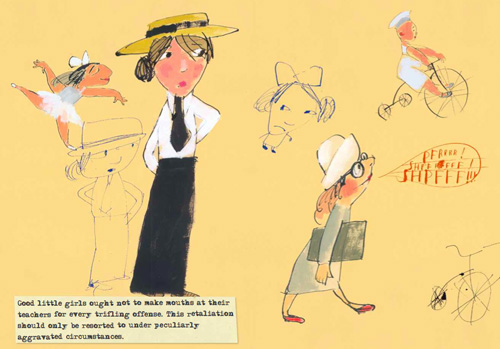

Good little girls ought not to make mouths at their teachers for every trifling offense. This retaliation should only be resorted to under peculiarly aggravated circumstances.

Good little girls ought not to make mouths at their teachers for every trifling offense. This retaliation should only be resorted to under peculiarly aggravated circumstances.

One can't help but wonder whether this particular bit may have in part inspired the irreverent 1964 anthology Beastly Boys and Ghastly Girls and its mischievous advice on brother-sister relations:

If your mother tells you to do a thing, it is wrong to reply that you won’t. It is better and more becoming to intimate that you will do as she bids you, and then afterward act quietly in the matter according to the dictates of your best judgment.

If your mother tells you to do a thing, it is wrong to reply that you won’t. It is better and more becoming to intimate that you will do as she bids you, and then afterward act quietly in the matter according to the dictates of your best judgment.

Good little girls always show marked deference for the aged. You ought never to 'sass' old people unless they 'sass' you first.

Good little girls always show marked deference for the aged. You ought never to 'sass' old people unless they 'sass' you first.

Originally featured in April – see more spreads, as well as the story behind the project, here.

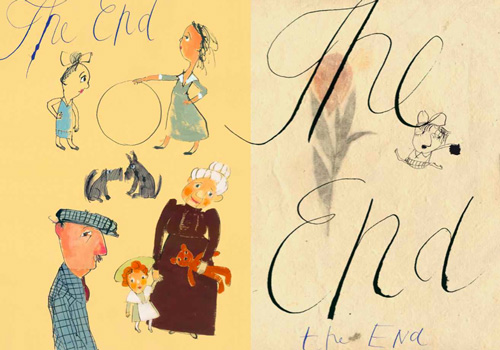

2. THE HOLE

The Hole (public library) by artist Øyvind Torseter, one of Norway's most celebrated illustrators, tells the story of a lovable protagonist who wakes up one day and discovers a mysterious hole in his apartment, which moves and seems to have a mind of its own. Befuddled, he looks for its origin – in vain. He packs it in a box and takes it to a lab, but still no explanation.

The Hole (public library) by artist Øyvind Torseter, one of Norway's most celebrated illustrators, tells the story of a lovable protagonist who wakes up one day and discovers a mysterious hole in his apartment, which moves and seems to have a mind of its own. Befuddled, he looks for its origin – in vain. He packs it in a box and takes it to a lab, but still no explanation.

With Torseter's minimalist yet visually eloquent pen-and-digital line drawings, vaguely reminiscent of Sir Quentin Blake and Tomi Ungerer yet decidedly distinctive, the story is at once simple and profound, amusing and philosophical, the sort of quiet meditation that gently, playfully tickles us into existential inquiry.

What makes the book especially magical is that a die-cut hole runs from the wonderfully gritty cardboard cover through every page and all the way out through the back cover – an especial delight for those of us who swoon over masterpieces of die-cut whimsy. In every page, the hole is masterfully incorporated into the visual narrative, adding an element of tactile delight that only an analog book can afford. The screen thus does it little justice, as these digital images feature a mere magenta-rimmed circle where the die-cut hole actually appears, but I've tried to capture its charm in a few photographs accompanying the page illustrations.

Originally featured in September, with lots more illustrations.

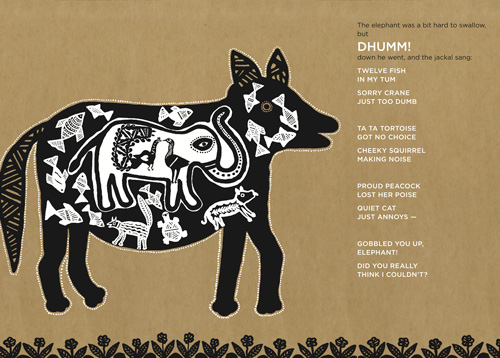

4. GOBBLE YOU UP

For nearly two decades, independent India-based publisher Tara Books has been giving voice to marginalized art and literature through a collective of artists, writers, and designers collaborating on beautiful books based on regional folk traditions, producing such gems as Waterlife, The Night Life of Trees, and Drawing from the City. A year after I Saw a Peacock with a Fiery Tail – one of the best art books of 2012, a magnificent 17th-century British “trick” poem adapted in a die-cut narrative and illustrated in the signature Indian folk art style of the Gond tribe – comes Gobble You Up (public library), an oral Rajasthani trickster tale adapted as a cumulative rhyme in a mesmerizing handmade treasure released in a limited edition of 7,000 numbered handmade copies, illustrated by artist Sunita and silkscreened by hand in two colors on beautifully coarse kraft paper custom-made for the project. What makes it especially extraordinary, however, is that the Mandna tradition of tribal finger-painting – an ancient Indian art form practiced only by women and passed down from mother to daughter across the generations, created by soaking pieces of cloth in chalk and lime paste, which the artist squeezes through her fingers into delicate lines on the mud walls of village huts – has never before been used to tell a children's story.

For nearly two decades, independent India-based publisher Tara Books has been giving voice to marginalized art and literature through a collective of artists, writers, and designers collaborating on beautiful books based on regional folk traditions, producing such gems as Waterlife, The Night Life of Trees, and Drawing from the City. A year after I Saw a Peacock with a Fiery Tail – one of the best art books of 2012, a magnificent 17th-century British “trick” poem adapted in a die-cut narrative and illustrated in the signature Indian folk art style of the Gond tribe – comes Gobble You Up (public library), an oral Rajasthani trickster tale adapted as a cumulative rhyme in a mesmerizing handmade treasure released in a limited edition of 7,000 numbered handmade copies, illustrated by artist Sunita and silkscreened by hand in two colors on beautifully coarse kraft paper custom-made for the project. What makes it especially extraordinary, however, is that the Mandna tradition of tribal finger-painting – an ancient Indian art form practiced only by women and passed down from mother to daughter across the generations, created by soaking pieces of cloth in chalk and lime paste, which the artist squeezes through her fingers into delicate lines on the mud walls of village huts – has never before been used to tell a children's story.

And what a story it is: A cunning jackal who decides to spare himself the effort of hunting for food by tricking his fellow forest creatures into being gobbled up whole, beginning with his friend the crane; he slyly swallows them one by one, until the whole menagerie fills his belly – a play on the classic Meena motif of the pregnant animal depicted with a baby inside its belly, reflecting the mother-daughter genesis of the ancient art tradition itself.

Indeed, Sunita herself was taught to paint by her mother and older sister – but unlike most Meena women, who don't usually leave the confines of their village and thus contain their art within their community, Sunita has thankfully ventured into the wider world, offering us a portal into this age-old wonderland of art and storytelling.

Gita Wolf, Tara's visionary founder, who envisioned the project and wrote the cumulative rhyme, describes the challenges of adapting this ephemeral, living art form onto the printed page without losing any of its expressive aliveness:

Illustrating the story in the Meena style of art involved two kinds of movement. The first was to build a visual narrative sequencing from a tradition which favored single, static images. The second challenge was to keep the quality of the wall art, while transferring it to a different, while also smaller, surface. We decided on using large sheets of brown paper, with Sunita squeezing diluted white acrylic paint through her fingers.

Illustrating the story in the Meena style of art involved two kinds of movement. The first was to build a visual narrative sequencing from a tradition which favored single, static images. The second challenge was to keep the quality of the wall art, while transferring it to a different, while also smaller, surface. We decided on using large sheets of brown paper, with Sunita squeezing diluted white acrylic paint through her fingers.

Originally featured in October – see more here.

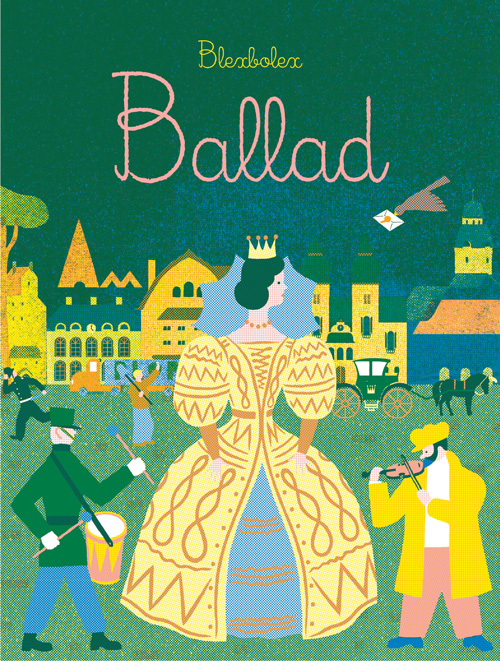

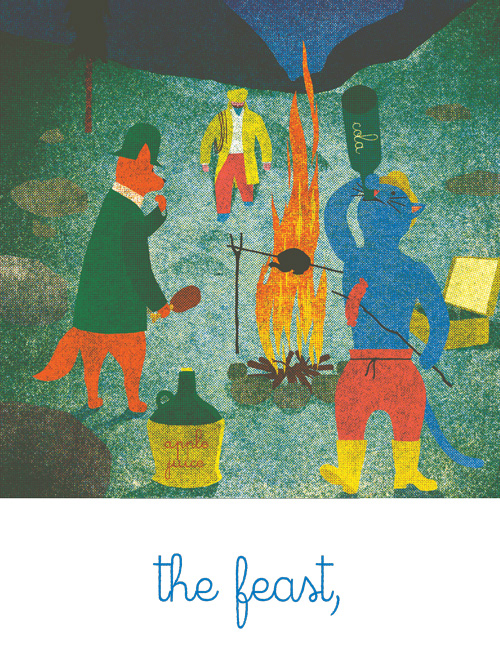

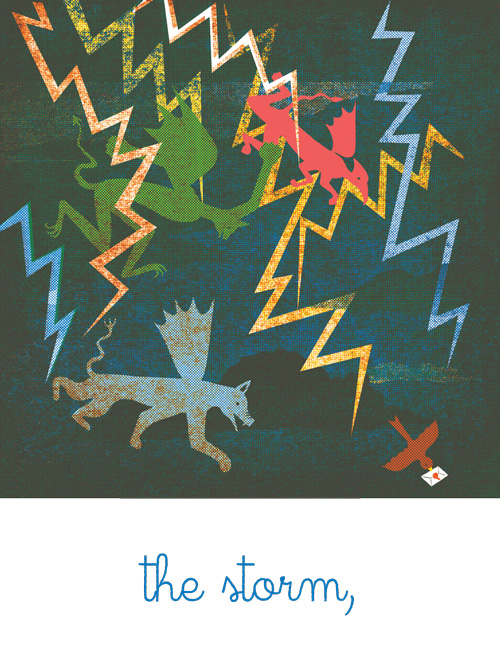

5. BALLAD

The best, most enchanting stories live somewhere between the creative nourishment of our daydreams and the dark allure of our nightmares. That's exactly where beloved French graphic artist Blexbolex transports us in Ballad (public library) – his exquisite and enthralling follow-up to People, one of the best illustrated books of 2011, and Seasons.

The best, most enchanting stories live somewhere between the creative nourishment of our daydreams and the dark allure of our nightmares. That's exactly where beloved French graphic artist Blexbolex transports us in Ballad (public library) – his exquisite and enthralling follow-up to People, one of the best illustrated books of 2011, and Seasons.

This continuously evolving story traces a child's perception of his surroundings as he walks home from school. It unfolds over seven sequences across 280 glorious pages and has an almost mathematical beauty to it as each sequence exponentially blossoms into the next: We begin with school, path, and home; we progress to school, street, path, forest, home; before we know it, there's a witch, a stranger, a sorcerer, a hot air balloon, and a kidnapped queen. All throughout, we're invited to reimagine the narrative as we absorb the growing complexity of the world – a beautiful allegory for our walk through life itself.

The frontispiece makes a simple and alluring promise:

It's a story as old as the world – a story that begins all over again each day.

It's a story as old as the world – a story that begins all over again each day.

Originally featured in October – see more here.

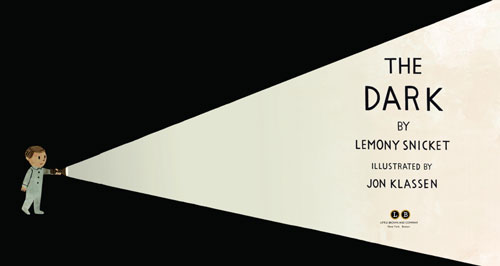

6. THE DARK

Daniel Handler – beloved author, timelessly heartening literary jukeboxer – is perhaps better-known by his pen name Lemony Snicket, under which he pens his endlessly delightful children's books. In fact, they owe much of their charisma to the remarkable creative collaborations Snicket spawns, from 13 Words illustrated by the inimitable Maira Kalman to Who Could It Be At This Hour? with artwork by celebrated cartoonist Seth. Snicket's 2013 gem, reminiscent in spirit of Maya Angelou's Life Doesn’t Frighten Me, is at least as exciting – a minimalist yet magnificently expressive story about a universal childhood fear, titled The Dark (public library) and illustrated by none other than Jon Klassen.

Daniel Handler – beloved author, timelessly heartening literary jukeboxer – is perhaps better-known by his pen name Lemony Snicket, under which he pens his endlessly delightful children's books. In fact, they owe much of their charisma to the remarkable creative collaborations Snicket spawns, from 13 Words illustrated by the inimitable Maira Kalman to Who Could It Be At This Hour? with artwork by celebrated cartoonist Seth. Snicket's 2013 gem, reminiscent in spirit of Maya Angelou's Life Doesn’t Frighten Me, is at least as exciting – a minimalist yet magnificently expressive story about a universal childhood fear, titled The Dark (public library) and illustrated by none other than Jon Klassen.

In a conversation with NPR, Handler echoes Aung San Suu Kyi's timeless wisdom on freedom from fear and articulates the deeper, more universal essence of the book's message:

I think books that are meant to be read in the nighttime ought to confront the very fears that we're trying to think about. And I think that a young reader of The Dark will encounter a story about a boy who makes new peace with a fear, rather than a story that ignores whatever troubles are lurking in the corners of our minds when we go to sleep.

I think books that are meant to be read in the nighttime ought to confront the very fears that we're trying to think about. And I think that a young reader of The Dark will encounter a story about a boy who makes new peace with a fear, rather than a story that ignores whatever troubles are lurking in the corners of our minds when we go to sleep.

Originally featured in June.

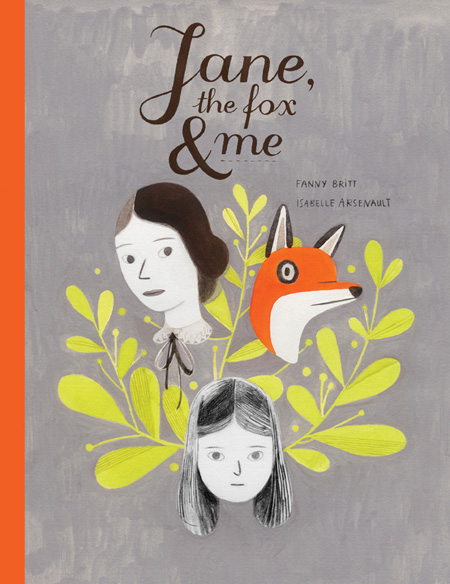

7. JANE, THE FOX AND ME

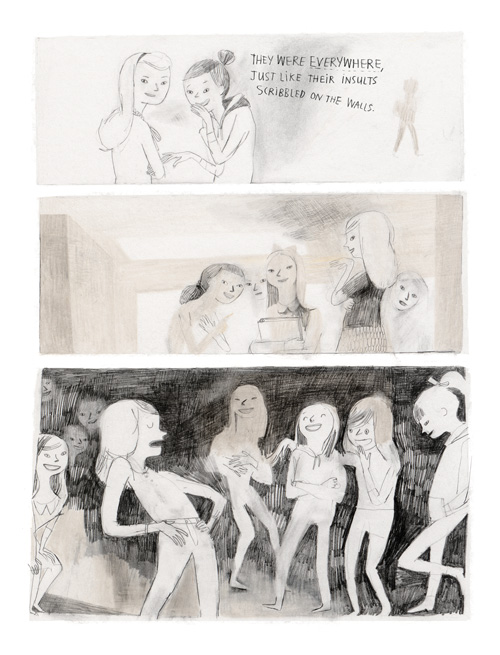

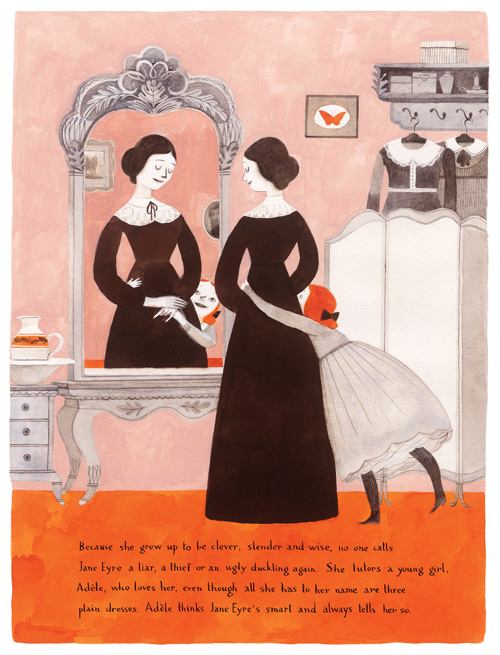

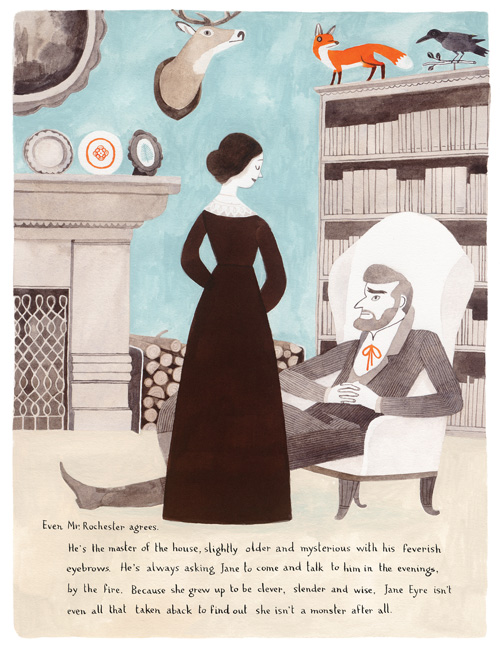

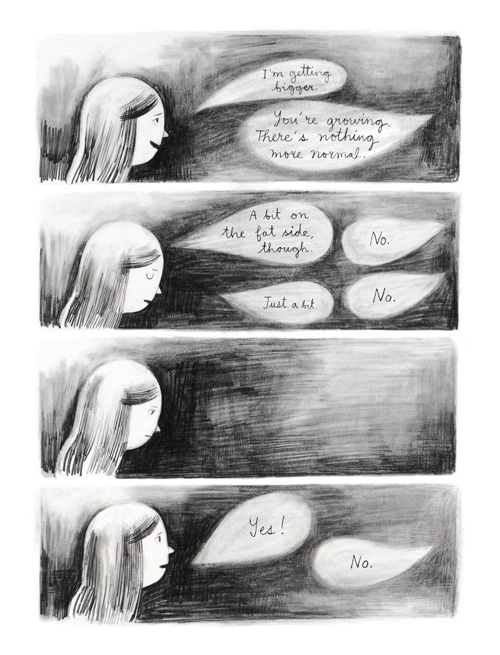

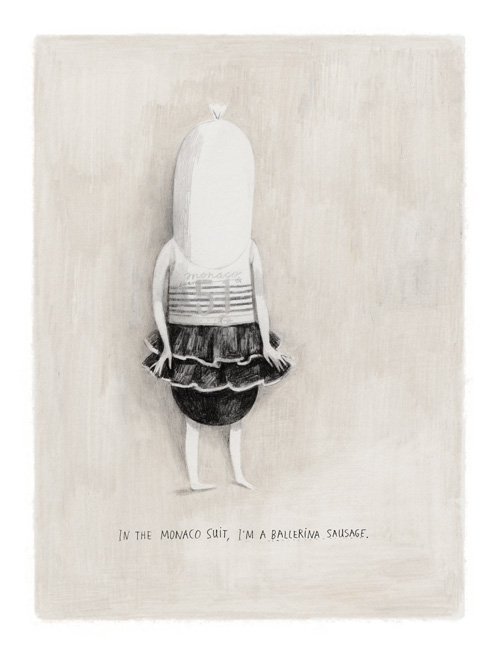

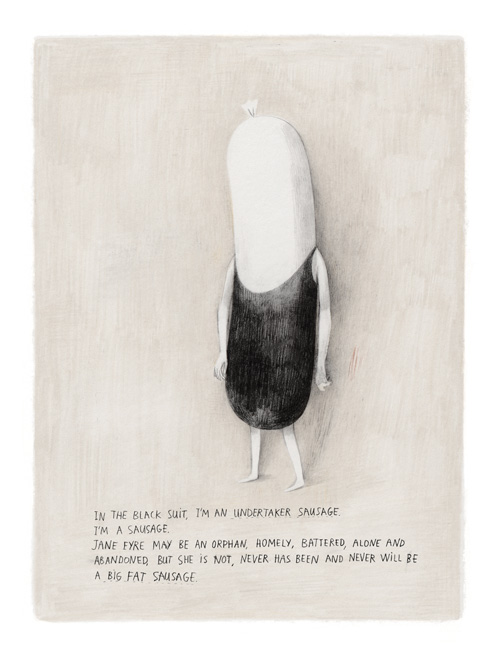

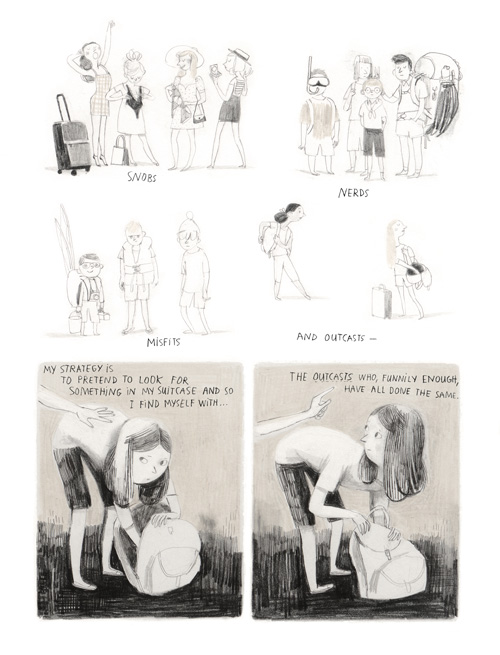

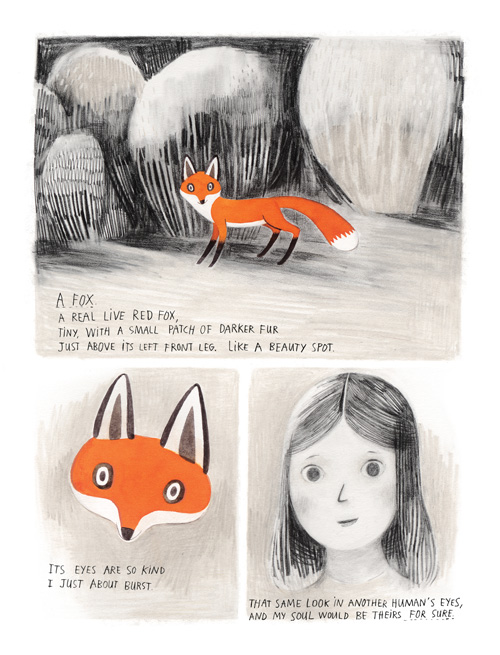

"Reading is escape, and the opposite of escape; it’s a way to make contact with reality," Nora Ephron wrote. "If I can't stand the world I just curl up with a book, and it's like a little spaceship that takes me away from everything," Susan Sontag told an interviewer, articulating an experience at once so common and so deeply personal to all of us who have ever taken refuge from the world in the pages of a book and the words of a beloved author. It's precisely this experience that comes vibrantly alive in Jane, the Fox, and Me (public library) – a stunningly illustrated graphic novel about a young girl named Hélène, who, cruelly teased by the "mean girls" clique at school, finds refuge in Charlotte Brönte’s Jane Eyre. In Jane, she sees both a kindred spirit and aspirational substance of character, one straddling the boundary between vulnerability and strength with remarkable grace – just the quality of heart and mind she needs as she confronts the common and heartbreaking trials of teenage girls tormented by bullying, by concerns over their emerging womanly shape, and by the soul-shattering feeling of longing for acceptance yet receiving none.

"Reading is escape, and the opposite of escape; it’s a way to make contact with reality," Nora Ephron wrote. "If I can't stand the world I just curl up with a book, and it's like a little spaceship that takes me away from everything," Susan Sontag told an interviewer, articulating an experience at once so common and so deeply personal to all of us who have ever taken refuge from the world in the pages of a book and the words of a beloved author. It's precisely this experience that comes vibrantly alive in Jane, the Fox, and Me (public library) – a stunningly illustrated graphic novel about a young girl named Hélène, who, cruelly teased by the "mean girls" clique at school, finds refuge in Charlotte Brönte’s Jane Eyre. In Jane, she sees both a kindred spirit and aspirational substance of character, one straddling the boundary between vulnerability and strength with remarkable grace – just the quality of heart and mind she needs as she confronts the common and heartbreaking trials of teenage girls tormented by bullying, by concerns over their emerging womanly shape, and by the soul-shattering feeling of longing for acceptance yet receiving none.

Written by Fanny Britt and illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault – the artist behind the magnificent Virginia Wolf, one of the best children's books of 2012 – this masterpiece of storytelling is as emotionally honest and psychologically insightful as it is graphically stunning. What makes the visual narrative especially enchanting is that Hélène's black-and-white world of daily sorrow springs to life in full color whenever she escapes with Brönte.

Originally featured in November – see more here.

8. MY FIRST KAFKA

Sylvia Plath believed it was never too early to dip children's toes in the vast body of literature. But to plunge straight into Kafka? Why not, which is precisely what Brooklyn-based writer and videogame designer Matthue Roth has done in My First Kafka: Runaways, Rodents, and Giant Bugs (public library) – a magnificent adaptation of Kafka for kids. With stunning black-and-white illustrations by London-based fine artist Rohan Daniel Eason, this gem falls – rises, rather – somewhere between Edward Gorey, Maurice Sendak, and the Graphic Canon series.

Sylvia Plath believed it was never too early to dip children's toes in the vast body of literature. But to plunge straight into Kafka? Why not, which is precisely what Brooklyn-based writer and videogame designer Matthue Roth has done in My First Kafka: Runaways, Rodents, and Giant Bugs (public library) – a magnificent adaptation of Kafka for kids. With stunning black-and-white illustrations by London-based fine artist Rohan Daniel Eason, this gem falls – rises, rather – somewhere between Edward Gorey, Maurice Sendak, and the Graphic Canon series.

The idea came to Roth after he accidentally started reading Kafka to his two little girls, who grew enchanted with the stories. As for the choice to adapt Kafka's characteristically dark sensibility for children, Roth clearly subscribes to the Sendakian belief that grown-ups project their own fears onto kids, who welcome rather than dread the dark. Indeed, it's hard not to see Sendak's fatherly echo in Eason's beautifully haunting black-and-white drawings.

Much like Jonathan Safran Foer used Street of Crocodiles to create his brilliant Tree of Codes literary remix and Darwin's great-granddaughter adapted the legendary naturalist's biography into verse, Roth scoured public domain texts and various translations of Kafka to find the perfect works for his singsong transformations: the short prose poem “Excursion into the Mountains,” the novella “The Metamorphosis,” which endures as Kafka's best-known masterpiece, and “Josefine the Singer," his final story.

Originally featured in July – see more here.

:: SEE FULL LIST / SHARE ::

In 2010, shame and empathy researcher Dr. Brené Brown gave us the wonderful and culturally necessary The Gifts of Imperfection, exploring the uncomfortable vulnerability and self-acceptance required in order to truly connect with others. In this charming short film, the folks of the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, better-known as the RSA, put a twist on their usual live-illustrated gems and take a page out of the TED-Ed book, teaming up with animator Katy Davis to bring to life an excerpt from Brown's longer talk on the power of vulnerability and the difference between empathy and sympathy, based on her most recent self-helpy-sounding but enormously insightful and rigorously researched book, Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead (public library).

In 2010, shame and empathy researcher Dr. Brené Brown gave us the wonderful and culturally necessary The Gifts of Imperfection, exploring the uncomfortable vulnerability and self-acceptance required in order to truly connect with others. In this charming short film, the folks of the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, better-known as the RSA, put a twist on their usual live-illustrated gems and take a page out of the TED-Ed book, teaming up with animator Katy Davis to bring to life an excerpt from Brown's longer talk on the power of vulnerability and the difference between empathy and sympathy, based on her most recent self-helpy-sounding but enormously insightful and rigorously researched book, Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead (public library).

The truth is, rarely can a response make something better – what makes something better is connection.

The truth is, rarely can a response make something better – what makes something better is connection.

And that connection often requires mutual vulnerability. Brown writes in Daring Greatly:

Vulnerability isn’t good or bad. It’s not what we call a dark emotion, nor is it always a light, positive experience. Vulnerability is the core of all emotions and feelings. To feel is to be vulnerable. To believe vulnerability is weakness is to believe that feeling is weakness. To foreclose on our emotional life out of a fear that the costs will be too high is to walk away from the very thing that gives purpose and meaning to living.

Vulnerability isn’t good or bad. It’s not what we call a dark emotion, nor is it always a light, positive experience. Vulnerability is the core of all emotions and feelings. To feel is to be vulnerable. To believe vulnerability is weakness is to believe that feeling is weakness. To foreclose on our emotional life out of a fear that the costs will be too high is to walk away from the very thing that gives purpose and meaning to living.

[…]

Vulnerability is the birthplace of love, belonging, joy, courage, empathy, accountability, and authenticity. If we want greater clarity in our purpose or deeper and more meaningful spiritual lives, vulnerability is the path.

Watch Brown's full RSA talk here.

:: WATCH / SHARE ::

On the heels of the year's best reads in psychology and philosophy, art and design, history and biography, and children's books, the season's subjective selection of best-of reading lists continues with the finest science and technology books of 2013. (For more timeless stimulation, revisit the selections for 2012 and 2011.)

1. THIS EXPLAINS EVERYTHING

Every year since 1998, intellectual impresario and Edge editor John Brockman has been posing a single grand question to some of our time's greatest thinkers across a wide spectrum of disciplines, then collecting the answers in an annual anthology. Last year's answers to the question "What scientific concept will improve everybody's cognitive toolkit?" were released in This Will Make You Smarter: New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking, one of the year's best psychology and philosophy books.

Every year since 1998, intellectual impresario and Edge editor John Brockman has been posing a single grand question to some of our time's greatest thinkers across a wide spectrum of disciplines, then collecting the answers in an annual anthology. Last year's answers to the question "What scientific concept will improve everybody's cognitive toolkit?" were released in This Will Make You Smarter: New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking, one of the year's best psychology and philosophy books.

In 2012, the question Brockman posed, proposed by none other than Steven Pinker, was "What is your favorite deep, elegant, or beautiful explanation?" The answers, representing an eclectic mix of 192 (alas, overwhelmingly male) minds spanning psychology, quantum physics, social science, political theory, philosophy, and more, are collected in the edited compendium This Explains Everything: Deep, Beautiful, and Elegant Theories of How the World Works (UK; public library) and are also available online.

In the introduction preceding the micro-essays, Brockman frames the question and its ultimate objective, adding to history's most timeless definitions of science:

The ideas presented on Edge are speculative; they represent the frontiers in such areas as evolutionary biology, genetics, computer science, neurophysiology, psychology, cosmology, and physics. Emerging out of these contributions is a new natural philosophy, new ways of understanding physical systems, new ways of thinking that call into question many of our basic assumptions.

The ideas presented on Edge are speculative; they represent the frontiers in such areas as evolutionary biology, genetics, computer science, neurophysiology, psychology, cosmology, and physics. Emerging out of these contributions is a new natural philosophy, new ways of understanding physical systems, new ways of thinking that call into question many of our basic assumptions.

[…]

Perhaps the greatest pleasure in science comes from theories that derive the solution to some deep puzzle from a small set of simple principles in a surprising way. These explanations are called 'beautiful' or 'elegant.'

[…]

The contributions presented here embrace scientific thinking in the broadest sense: as the most reliable way of gaining knowledge about anything – including such fields of inquiry as philosophy, mathematics, economics, history, language, and human behavior. The common thread is that a simple and nonobvious idea is proposed as the explanation of a diverse and complicated set of phenomena.

Originally featured in January – read more here, including excepts from some of the essays.

2. ON LOOKING

"How we spend our days," Annie Dillard wrote in her timelessly beautiful meditation on presence over productivity, "is, of course, how we spend our lives." And nowhere do we fail at the art of presence most miserably and most tragically than in urban life – in the city, high on the cult of productivity, where we float past each other, past the buildings and trees and the little boy in the purple pants, past life itself, cut off from the breathing of the world by iPhone earbuds and solipsism. And yet: “The art of seeing has to be learned,” Marguerite Duras reverberates – and it can be learned, as cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz invites us to believe in her breathlessly wonderful On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes (public library), also among the best psychology and philosophy books of the year – a record of her quest to walk around a city block with eleven different "experts," from an artist to a geologist to a dog, and emerge with fresh eyes mesmerized by the previously unseen fascinations of a familiar world. It is undoubtedly one of the most stimulating books of the year, if not the decade, and the most enchanting thing I've read in ages. In a way, it's the opposite but equally delightful mirror image of Christoph Niemann's Abstract City – a concrete, immersive examination of urbanity – blending the mindfulness of Sherlock Holmes with the expansive sensitivity of Thoreau.

"How we spend our days," Annie Dillard wrote in her timelessly beautiful meditation on presence over productivity, "is, of course, how we spend our lives." And nowhere do we fail at the art of presence most miserably and most tragically than in urban life – in the city, high on the cult of productivity, where we float past each other, past the buildings and trees and the little boy in the purple pants, past life itself, cut off from the breathing of the world by iPhone earbuds and solipsism. And yet: “The art of seeing has to be learned,” Marguerite Duras reverberates – and it can be learned, as cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz invites us to believe in her breathlessly wonderful On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes (public library), also among the best psychology and philosophy books of the year – a record of her quest to walk around a city block with eleven different "experts," from an artist to a geologist to a dog, and emerge with fresh eyes mesmerized by the previously unseen fascinations of a familiar world. It is undoubtedly one of the most stimulating books of the year, if not the decade, and the most enchanting thing I've read in ages. In a way, it's the opposite but equally delightful mirror image of Christoph Niemann's Abstract City – a concrete, immersive examination of urbanity – blending the mindfulness of Sherlock Holmes with the expansive sensitivity of Thoreau.

Horowitz begins by pointing our attention to the incompleteness of our experience of what we conveniently call "reality":

Right now, you are missing the vast majority of what is happening around you. You are missing the events unfolding in your body, in the distance, and right in front of you.

Right now, you are missing the vast majority of what is happening around you. You are missing the events unfolding in your body, in the distance, and right in front of you.

By marshaling your attention to these words, helpfully framed in a distinct border of white, you are ignoring an unthinkably large amount of information that continues to bombard all of your senses: the hum of the fluorescent lights, the ambient noise in a large room, the places your chair presses against your legs or back, your tongue touching the roof of your mouth, the tension you are holding in your shoulders or jaw, the map of the cool and warm places on your body, the constant hum of traffic or a distant lawn-mower, the blurred view of your own shoulders and torso in your peripheral vision, a chirp of a bug or whine of a kitchen appliance.

This adaptive ignorance, she argues, is there for a reason – we celebrate it as "concentration" and welcome its way of easing our cognitive overload by allowing us to conserve our precious mental resources only for the stimuli of immediate and vital importance, and to dismiss or entirely miss all else. ("Attention is an intentional, unapologetic discriminator," Horowitz tells us. "It asks what is relevant right now, and gears us up to notice only that.") But while this might make us more efficient in our goal-oriented day-to-day, it also makes us inhabit a largely unlived – and unremembered – life, day in and day out.

For Horowitz, the awakening to this incredible, invisible backdrop of life came thanks to Pumpernickel, her "curly haired, sage mixed breed" (who also inspired Horowitz's first book, the excellent Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know), as she found herself taking countless walks around the block, becoming more and more aware of the dramatically different experiences she and her canine companion were having along the exact same route:

Minor clashes between my dog’s preferences as to where and how a walk should proceed and my own indicated that I was experiencing almost an entirely different block than my dog. I was paying so little attention to most of what was right before us that I had become a sleepwalker on the sidewalk. What I saw and attended to was exactly what I expected to see; what my dog showed me was that my attention invited along attention’s companion: inattention to everything else.

Minor clashes between my dog’s preferences as to where and how a walk should proceed and my own indicated that I was experiencing almost an entirely different block than my dog. I was paying so little attention to most of what was right before us that I had become a sleepwalker on the sidewalk. What I saw and attended to was exactly what I expected to see; what my dog showed me was that my attention invited along attention’s companion: inattention to everything else.

The book was her answer to the disconnect, an effort to "attend to that inattention." It is not, she warns us, "about how to bring more focus to your reading of Tolstoy or how to listen more carefully to your spouse." Rather, it is an invitation to the art of observation:

Together, we became investigators of the ordinary, considering the block – the street and everything on it—as a living being that could be observed.

Together, we became investigators of the ordinary, considering the block – the street and everything on it—as a living being that could be observed.

In this way, the familiar becomes unfamiliar, and the old the new.

Her approach is based on two osmotic human tendencies: our shared capacity to truly see what is in front of us, despite our conditioned concentration that obscures it, and the power of individual bias in perception – or what we call "expertise," acquired by passion or training or both – in bringing attention to elements that elude the rest of us. What follows is a whirlwind of endlessly captivating exercises in attentive bias as Horowitz, with her archetypal New Yorker's "special fascination with the humming life-form that is an urban street," and her diverse companions take to the city.

First, she takes a walk all by herself, trying to note everything observable, and we quickly realize that besides her deliciously ravenous intellectual curiosity, Horowitz is a rare magician with language. ("The walkers trod silently; the dogs said nothing. The only sound was the hum of air conditioners," she beholds her own block; passing a pile of trash bags graced by a stray Q-tip, she ponders parenthetically, "how does a Q-tip escape?"; turning her final corner, she gazes at the entrance of a mansion and "its pair of stone lions waiting patiently for royalty that never arrives." Stunning.)

But as soon as she joins her experts, Horowitz is faced with the grimacing awareness that despite her best, most Sherlockian efforts, she was "missing pretty much everything." She arrives at a newfound, profound understanding of what William James meant when he wrote, "My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind.":

I would find myself at once alarmed, delighted, and humbled at the limitations of my ordinary looking. My consolation is that this deficiency of mine is quite human. We see, but we do not see: we use our eyes, but our gaze is glancing, frivolously considering its object. We see the signs, but not their meanings. We are not blinded, but we have blinders.

I would find myself at once alarmed, delighted, and humbled at the limitations of my ordinary looking. My consolation is that this deficiency of mine is quite human. We see, but we do not see: we use our eyes, but our gaze is glancing, frivolously considering its object. We see the signs, but not their meanings. We are not blinded, but we have blinders.

Originally featured in August, with a closer look at the expert insights. For another peek at this gem, which is easily among my top three favorite books of the past decade, learn how to do the step-and-slide.

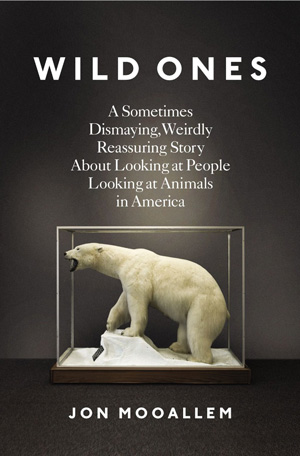

3. WILD ONES

Wild Ones: A Sometimes Dismaying, Weirdly Reassuring Story About Looking at People Looking at Animals in America (public library) by journalist Jon Mooallem isn't the typical story designed to make us better by making us feel bad, to scare us into behaving, into environmental empathy; Mooallem's is not the self-righteous tone of capital-K knowing typical of many environmental activists but the scientist's disposition of not-knowing, the poet's penchant for "negative capability." Rather than ready-bake answers, he offers instead directions of thought and signposts for curiosity and, in the process, somehow gently moves us a little bit closer to our better selves, to a deep sense of, as poet Diane Ackerman beautifully put it in 1974, "the plain everythingness of everything, in cahoots with the everythingness of everything else."

Wild Ones: A Sometimes Dismaying, Weirdly Reassuring Story About Looking at People Looking at Animals in America (public library) by journalist Jon Mooallem isn't the typical story designed to make us better by making us feel bad, to scare us into behaving, into environmental empathy; Mooallem's is not the self-righteous tone of capital-K knowing typical of many environmental activists but the scientist's disposition of not-knowing, the poet's penchant for "negative capability." Rather than ready-bake answers, he offers instead directions of thought and signposts for curiosity and, in the process, somehow gently moves us a little bit closer to our better selves, to a deep sense of, as poet Diane Ackerman beautifully put it in 1974, "the plain everythingness of everything, in cahoots with the everythingness of everything else."

In the introduction, Mooallem recalls looking at his four-year-old daughter Isla's menagerie of stuffed animals and the odd cultural disconnect they mime:

[T]hey were foraging on the pages of every bedtime story, and my daughter was sleeping in polar bear pajamas under a butterfly mobile with a downy snow owl clutched to her chin. Her comb handle was a fish. Her toothbrush handle was a whale. She cut her first tooth on a rubber giraffe.

Our world is different, zoologically speaking – less straightforward and more grisly. We are living in the eye of a great storm of extinction, on a planet hemorrhaging living things so fast that half of its nine million species could be gone by the end of the century. At my place, the teddy bears and giggling penguins kept coming. But I didn’t realize the lengths to which humankind now has to go to keep some semblance of actual wildlife in the world. As our own species has taken over, we’ve tried to retain space for at least some of the others being pushed aside, shoring up their chances of survival. But the threats against them keep multiplying and escalating. Gradually, America’s management of its wild animals has evolved, or maybe devolved, into a surreal kind of performance art.

[T]hey were foraging on the pages of every bedtime story, and my daughter was sleeping in polar bear pajamas under a butterfly mobile with a downy snow owl clutched to her chin. Her comb handle was a fish. Her toothbrush handle was a whale. She cut her first tooth on a rubber giraffe.

Our world is different, zoologically speaking – less straightforward and more grisly. We are living in the eye of a great storm of extinction, on a planet hemorrhaging living things so fast that half of its nine million species could be gone by the end of the century. At my place, the teddy bears and giggling penguins kept coming. But I didn’t realize the lengths to which humankind now has to go to keep some semblance of actual wildlife in the world. As our own species has taken over, we’ve tried to retain space for at least some of the others being pushed aside, shoring up their chances of survival. But the threats against them keep multiplying and escalating. Gradually, America’s management of its wild animals has evolved, or maybe devolved, into a surreal kind of performance art.

He finds himself uncomfortably straddling these two animal worlds – the idyllic little-kid's dreamland and the messy, fragile ecosystem of the real world:

Once I started looking around, I noticed the same kind of secondhand fauna that surrounds my daughter embellishing the grown-up world, too – not just the conspicuous bald eagle on flagpoles and currency, or the big-cat and raptor names we give sports teams and computer operating systems, but the whale inexplicably breaching in the life-insurance commercial, the glass dolphin dangling from a rearview mirror, the owl sitting on the rump of a wild boar silk-screened on a hipster’s tote bag. I spotted wolf after wolf airbrushed on the sides of old vans, and another wolf, painted against a full moon on purple velvet, greeting me over the toilet in a Mexican restaurant bathroom. … [But] maybe we never outgrow the imaginary animal kingdom of childhood. Maybe it’s the one we are trying to save.

Once I started looking around, I noticed the same kind of secondhand fauna that surrounds my daughter embellishing the grown-up world, too – not just the conspicuous bald eagle on flagpoles and currency, or the big-cat and raptor names we give sports teams and computer operating systems, but the whale inexplicably breaching in the life-insurance commercial, the glass dolphin dangling from a rearview mirror, the owl sitting on the rump of a wild boar silk-screened on a hipster’s tote bag. I spotted wolf after wolf airbrushed on the sides of old vans, and another wolf, painted against a full moon on purple velvet, greeting me over the toilet in a Mexican restaurant bathroom. … [But] maybe we never outgrow the imaginary animal kingdom of childhood. Maybe it’s the one we are trying to save.

[…]

From the very beginning, America’s wild animals have inhabited the terrain of our imagination just as much as they‘ve inhabited the actual land. They are free-roaming Rorschachs, and we are free to spin whatever stories we want about them. The wild animals always have no comment.

So he sets out to better understand the dynamics of the cultural forces that pull these worlds together with shared abstractions and rip them apart with the brutal realities of environmental collapse. His quest, in which little Isla is a frequent companion, sends him on the trails of three endangered species – a bear, a butterfly, and a bird – which fall on three different points on the spectrum of conservation reliance, relying to various degrees on the mercy of the very humans who first disrupted "the machinery of their wildness." On the way, he encounters a remarkably vibrant cast of characters – countless passionate citizen scientists, a professional theater actor who, after an HIV diagnosis, became a professional butterfly enthusiast, and even Martha Stewart – and finds in their relationship with the environment "the same creeping disquiet about the future" that Mooallem himself came to know when he became a father.

Originally featured in May – read more here.

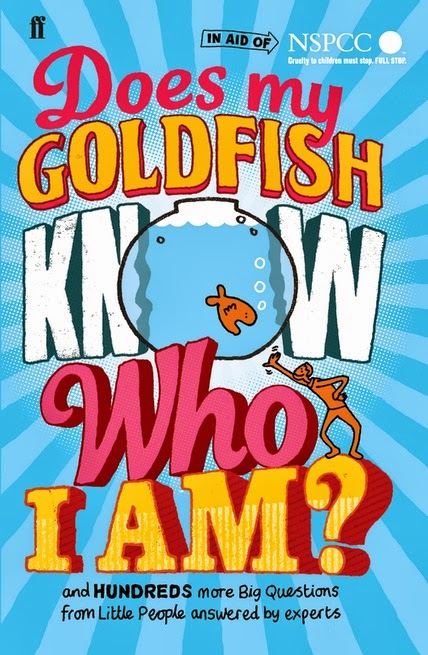

4. DOES MY GOLDFISH KNOW WHO I AM?

In 2012, I wrote about a lovely book titled Big Questions from Little People & Simple Answers from Great Minds, in which some of today's greatest scientists, writers, and philosophers answer kids' most urgent questions, deceptively simple yet profound. It went on to become one of the year's best books and among readers' favorites. A few months later, Gemma Elwin Harris, the editor who had envisioned the project, reached out to invite me to participate in the book's 2013 edition by answering one randomly assigned question from a curious child. Naturally, I was thrilled to do it, and honored to be a part of something as heartening as Does My Goldfish Know Who I Am? (public library), also among the best children's books of the year – a compendium of primary school children's funny, poignant, innocent yet insightful questions about science and how life works, answered by such celebrated minds as rockstar physicist Brian Cox, beloved broadcaster and voice-of-nature Sir David Attenborough, legendary linguist Noam Chomsky, science writer extraordinaire Mary Roach, stat-showman Hans Rosling, Beatle Paul McCartney, biologist and Beagle Project director Karen James, and iconic illustrator Sir Quentin Blake. As was the case with last year's edition, more than half of the proceeds from the book – which features illustrations by the wonderful Andy Smith – are being donated to a children's charity.

In 2012, I wrote about a lovely book titled Big Questions from Little People & Simple Answers from Great Minds, in which some of today's greatest scientists, writers, and philosophers answer kids' most urgent questions, deceptively simple yet profound. It went on to become one of the year's best books and among readers' favorites. A few months later, Gemma Elwin Harris, the editor who had envisioned the project, reached out to invite me to participate in the book's 2013 edition by answering one randomly assigned question from a curious child. Naturally, I was thrilled to do it, and honored to be a part of something as heartening as Does My Goldfish Know Who I Am? (public library), also among the best children's books of the year – a compendium of primary school children's funny, poignant, innocent yet insightful questions about science and how life works, answered by such celebrated minds as rockstar physicist Brian Cox, beloved broadcaster and voice-of-nature Sir David Attenborough, legendary linguist Noam Chomsky, science writer extraordinaire Mary Roach, stat-showman Hans Rosling, Beatle Paul McCartney, biologist and Beagle Project director Karen James, and iconic illustrator Sir Quentin Blake. As was the case with last year's edition, more than half of the proceeds from the book – which features illustrations by the wonderful Andy Smith – are being donated to a children's charity.

The questions range from what the purpose of science is to why onions make us cry to whether spiders can speak to why we blink when we sneeze. Psychologist and broadcaster Claudia Hammond, who recently explained the fascinating science of why time slows down when we're afraid, speeds up as we age, and gets all warped while we're on vacation in one of the best psychology and philosophy books of 2013, answers the most frequently asked question by the surveyed children: Why do we cry?

It’s normal to cry when you feel upset and until the age of twelve boys cry just as often as girls. But when you think about it, it is a bit strange that salty water spills out from the corners of your eyes just because you feel sad.

It’s normal to cry when you feel upset and until the age of twelve boys cry just as often as girls. But when you think about it, it is a bit strange that salty water spills out from the corners of your eyes just because you feel sad.

One professor noticed people often say that, despite their blotchy faces, a good cry makes them feel better. So he did an experiment where people had to breathe in over a blender full of onions that had just been chopped up. Not surprisingly this made their eyes water. He collected the tears and put them in the freezer. Then he got people to sit in front of a very sad film wearing special goggles which had tiny buckets hanging off the bottom, ready to catch their tears if they cried. The people cried, but the buckets didn’t work and in the end he gathered their tears in tiny test tubes instead.

He found that the tears people cried when they were upset contained extra substances, which weren’t in the tears caused by the onions. So he thinks maybe we feel better because we get rid of these substances by crying and that this is the purpose of tears.

But not everyone agrees. Many psychologists think that the reason we cry is to let other people know that we need their sympathy or help. So crying, provided we really mean it, brings comfort because people are nice to us.

Crying when we’re happy is a bit more of a mystery, but strong emotions have a lot in common, whether happy or sad, so they seem to trigger some of the same processes in the body.

(For a deeper dive into the biological mystery of crying, see the science of sobbing and emotional tearing.)

Joshua Foer, who knows a thing or two about superhuman memory and the limits of our mind, explains to 9-year-old Tom how the brain can store so much information despite being that small:

An adult’s brain only weighs about 1.4 kilograms, but it’s made up of about 100 billion microscopic neurons. Each of those neurons looks like a tiny branching tree, whose limbs reach out and touch other neurons. In fact, each neuron can make between 5,000 and 10,000 connections with other neurons – sometimes even more. That’s more than 500 trillion connections! A memory is essentially a pattern of connections between neurons.

An adult’s brain only weighs about 1.4 kilograms, but it’s made up of about 100 billion microscopic neurons. Each of those neurons looks like a tiny branching tree, whose limbs reach out and touch other neurons. In fact, each neuron can make between 5,000 and 10,000 connections with other neurons – sometimes even more. That’s more than 500 trillion connections! A memory is essentially a pattern of connections between neurons.

Every sensation that you remember, every thought that you think, transforms your brain by altering the connections within that vast network. By the time you get to the end of this sentence, you will have created a new memory, which means your brain will have physically changed.

Neuroscientist Tali Sharot, who has previously studied why our brains are wired for optimism, answers 8-year-old Maia's question about why we don't have memories from the time we were babies and toddlers:

We use our brain for memory. In the first few years of our lives, our brain grows and changes a lot, just like the rest of our body. Scientists think that because the parts of our brain that are important for memory have not fully developed when we are babies, we are unable to store memories in the same way that we do when we are older.

We use our brain for memory. In the first few years of our lives, our brain grows and changes a lot, just like the rest of our body. Scientists think that because the parts of our brain that are important for memory have not fully developed when we are babies, we are unable to store memories in the same way that we do when we are older.

Also, when we are very young we do not know how to speak. This makes it difficult to keep events in your mind and remember them later, because we use language to remember what happened in the past.

And my answer, to 9-year-old Ottilie's question about why we have books:

Some people might tell you that books are no longer necessary now that we have the internet. Don’t believe them. Books help us know other people, know how the world works, and, in the process, know ourselves more deeply in a way that has nothing to with what you read them on and everything to do with the curiosity, integrity and creative restlessness you bring to them.

Some people might tell you that books are no longer necessary now that we have the internet. Don’t believe them. Books help us know other people, know how the world works, and, in the process, know ourselves more deeply in a way that has nothing to with what you read them on and everything to do with the curiosity, integrity and creative restlessness you bring to them.

Books build bridges to the lives of others, both the characters in them and your countless fellow readers across other lands and other eras, and in doing so elevate you and anchor you more solidly into your own life. They give you a telescope into the minds of others, through which you begin to see with ever greater clarity the starscape of your own mind.

And though the body and form of the book will continue to evolve, its heart and soul never will. Though the telescope might change, the cosmic truths it invites you to peer into remain eternal like the Universe.

In many ways, books are the original internet – each fact, each story, each new bit of information can be a hyperlink to another book, another idea, another gateway into the endlessly whimsical rabbit hole of the written word. Just like the web pages you visit most regularly, your physical bookmarks take you back to those book pages you want to return to again and again, to reabsorb and relive, finding new meaning on each visit – because the landscape of your life is different, new, "reloaded" by the very act of living.

:: SEE FULL LIST / SHARE ::