Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – why the capacity for boredom is essential for a full life, Anna Deavere Smith on discipline and how stop letting others define us, Albert Camus on happiness and love, the psychology of your future self, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – why the capacity for boredom is essential for a full life, Anna Deavere Smith on discipline and how stop letting others define us, Albert Camus on happiness and love, the psychology of your future self, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

In 2013, Neil deGrasse Tyson hosted a mind-bending debate on the nature of "nothing" – an inquiry that has occupied thinkers since the dawn of recorded thought and permeates everything from Hamlet's iconic question to the boldest frontiers of quantum physics. That's precisely what New Scientist editor-in-chief Jeremy Webb explores with a kaleidoscopic lens in Nothing: Surprising Insights Everywhere from Zero to Oblivion (public library) – a terrific collection of essays and articles exploring everything from vacuum to the birth and death of the universe to how the concept of zero gained wide acceptance in the 17th century after being shunned as a dangerous innovation for 400 years. As Webb elegantly puts it, "nothing becomes a lens through which we can explore the universe around us and even what it is to be human. It reveals past attitudes and present thinking."

In 2013, Neil deGrasse Tyson hosted a mind-bending debate on the nature of "nothing" – an inquiry that has occupied thinkers since the dawn of recorded thought and permeates everything from Hamlet's iconic question to the boldest frontiers of quantum physics. That's precisely what New Scientist editor-in-chief Jeremy Webb explores with a kaleidoscopic lens in Nothing: Surprising Insights Everywhere from Zero to Oblivion (public library) – a terrific collection of essays and articles exploring everything from vacuum to the birth and death of the universe to how the concept of zero gained wide acceptance in the 17th century after being shunned as a dangerous innovation for 400 years. As Webb elegantly puts it, "nothing becomes a lens through which we can explore the universe around us and even what it is to be human. It reveals past attitudes and present thinking."

Among the most intensely interesting pieces in the collection is one by science journalist Jo Marchant, who penned the fascinating story of the world's oldest analog computer. Titled "Heal Thyself," the piece explores how the way we think about medical treatments shapes their very real, very physical effects on our bodies – an almost Gandhi-like proposition, except rooted in science rather than philosophy. Specifically, Marchant brings to light a striking new dimension of the placebo effect that runs counter to how the phenomenon has been conventionally explained. She writes:

It has always been assumed that the placebo effect only works if people are conned into believing that they are getting an actual active drug. But now it seems this may not be true. Belief in the placebo effect itself – rather than a particular drug – might be enough to encourage our bodies to heal.

It has always been assumed that the placebo effect only works if people are conned into believing that they are getting an actual active drug. But now it seems this may not be true. Belief in the placebo effect itself – rather than a particular drug – might be enough to encourage our bodies to heal.

She cites a recent study at the Harvard Medical School, in which people with irritable bowel syndrome were given a placebo and informed that the pills were “made of an inert substance, like sugar pills, that have been shown in clinical studies to produce significant improvement in IBS symptoms through mind-body self-healing processes.” As Marchant notes, this is absolutely true, in a meta kind of way. What the researchers found was startling in its implications for medicine, philosophy, and spirituality – despite being aware they were taking placebos, the participants rated their symptoms as "moderately improved" on average. In other words, they knew what they were taking wasn't a drug – it was a medical "nothing" – but the very consciousness of taking something made them experience fewer symptoms.

Illustration by Marianne Dubuc from The Lion and the Bird

This dovetails into recent research confirming what Helen Keller fervently believed by putting some serious science behind the value of optimism. Marchant sums up the findings:

Realism can be bad for your health. Optimists recover better from medical procedures such as coronary bypass surgery, have healthier immune systems and live longer, both in general and when suffering from conditions such as cancer, heart disease and kidney failure.

Realism can be bad for your health. Optimists recover better from medical procedures such as coronary bypass surgery, have healthier immune systems and live longer, both in general and when suffering from conditions such as cancer, heart disease and kidney failure.

It is well accepted that negative thoughts and anxiety can make us ill. Stress – the belief that we are at risk – triggers physiological pathways such as the “fight-or-flight” response, mediated by the sympathetic nervous system. These have evolved to protect us from danger, but if switched on long-term they increase the risk of conditions such as diabetes and dementia.

What researchers are now realizing is that positive beliefs don’t just work by quelling stress. They have a positive effect too – feeling safe and secure, or believing things will turn out fine, seems to help the body maintain and repair itself… Optimism seems to reduce stress-induced inflammation and levels of stress hormones such as cortisol. It may also reduce susceptibility to disease by dampening sympathetic nervous system activity and stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system. The latter governs what’s called the “rest-and-digest” response – the opposite of fight-or-flight.

Just as helpful as taking a rosy view of the future is having a rosy view of yourself. High “self-enhancers” – people who see themselves in a more positive light than others see them – have lower cardiovascular responses to stress and recover faster, as well as lower baseline cortisol levels.

Marchant notes that it's as beneficial to amplify the world's perceived positivity as it is to amplify our own – something known as our "self-enhancement bias," a type of self-delusion that helps keep us sane. But the same applies to our attitudes toward others as well – they too can impact our physical health. She cites University of Chicago psychologist John Cacioppo, who has dedicated his career to studying how social isolation affects individuals. Though solitude might be essential for great writing, being alone a special form of art, and single living the defining modality of our time, loneliness is a different thing altogether – a thing Cacioppo found to be toxic:

Being lonely increases the risk of everything from heart attacks to dementia, depression and death, whereas people who are satisfied with their social lives sleep better, age more slowly and respond better to vaccines. The effect is so strong that curing loneliness is as good for your health as giving up smoking.

Being lonely increases the risk of everything from heart attacks to dementia, depression and death, whereas people who are satisfied with their social lives sleep better, age more slowly and respond better to vaccines. The effect is so strong that curing loneliness is as good for your health as giving up smoking.

Illustration by Marianne Dubuc from The Lion and the Bird

Marchant quotes another researcher, Charles Raison at Atlanta's Emory University, who studies mind–body interactions:

It’s probably the single most powerful behavioral finding in the world… People who have rich social lives and warm, open relationships don’t get sick and they live longer.

It’s probably the single most powerful behavioral finding in the world… People who have rich social lives and warm, open relationships don’t get sick and they live longer.

Marchant points to specific research by Cacioppo, who found that "in lonely people, genes involved in cortisol signaling and the inflammatory response were up-regulated, and that immune cells important in fighting bacteria were more active, too." Marchant explains the findings and the essential caveat to them:

[Cacioppo] suggests that our bodies may have evolved so that in situations of perceived social isolation, they trigger branches of the immune system involved in wound healing and bacterial infection. An isolated person would be at greater risk of physical trauma, whereas being in a group might favor the immune responses necessary for fighting viruses, which spread easily between people in close contact.

[Cacioppo] suggests that our bodies may have evolved so that in situations of perceived social isolation, they trigger branches of the immune system involved in wound healing and bacterial infection. An isolated person would be at greater risk of physical trauma, whereas being in a group might favor the immune responses necessary for fighting viruses, which spread easily between people in close contact.

Crucially, these differences relate most strongly to how lonely people think they are, rather than to the actual size of their social network. That also makes sense from an evolutionary point of view, says Cacioppo, because being among hostile strangers can be just as dangerous as being alone. So ending loneliness is not about spending more time with people. Cacioppo thinks it is all about our attitude to others: lonely people become overly sensitive to social threats and come to see others as potentially dangerous. In a review of previous studies … he found that tackling this attitude reduced loneliness more effectively than giving people more opportunities for interaction, or teaching social skills.

Illustration by André François for Little Boy Brown, a lovely vintage ode to childhood and loneliness

Paradoxically, science suggests that one of the most important interventions to offer benefits that counter the ill effects of loneliness has to do with solitude – or, more precisely, regimented solitude in the form of meditation. Marchant notes that trials on the effects of meditation have been small – something I find troublesomely emblematic of the short-sightedness with which we approach mental health as we continue to prioritize the physical in both our clinical subsidies and our everyday lives (how many people have a workout routine compared to those with a meditation practice?); even within the study of mental health, the vast majority of medical research focuses on the effects of a physical substance – a drug of some sort – on the mind, with very little effort directed at understanding the effects of the mind on the physical body.

Still, the modest body of research on meditation is heartening. Marchant writes:

There is some evidence that meditation boosts the immune response in vaccine recipients and people with cancer, protects against a relapse in major depression, soothes skin conditions and even slows the progression of HIV. Meditation might even slow the aging process. Telomeres, the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes, get shorter every time a cell divides and so play a role in aging. Clifford Saron of the Center for Mind and Brain at the University of California, Davis, and colleagues showed in 2011 that levels of an enzyme that builds up telomeres were higher in people who attended a three-month meditation retreat than in a control group.

There is some evidence that meditation boosts the immune response in vaccine recipients and people with cancer, protects against a relapse in major depression, soothes skin conditions and even slows the progression of HIV. Meditation might even slow the aging process. Telomeres, the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes, get shorter every time a cell divides and so play a role in aging. Clifford Saron of the Center for Mind and Brain at the University of California, Davis, and colleagues showed in 2011 that levels of an enzyme that builds up telomeres were higher in people who attended a three-month meditation retreat than in a control group.

As with social interaction, meditation probably works largely by influencing stress response pathways. People who meditate have lower cortisol levels, and one study showed they have changes in their amygdala, a brain area involved in fear and the response to threat.

If you're intimidated by the time investment, take heart – fMRI studies show that as little as 11 hours of total training, or an hour every other day for three weeks, can produce structural changes in the brain. If you're considering dipping your toes in the practice, I wholeheartedly recommend meditation teacher Tara Brach, who has changed my life.

But perhaps the most striking finding in exploring how our beliefs affect our bodies has to do with finding your purpose and, more than that, finding meaning in life. The most prominent studies in the field have defined purpose rather narrowly, as religious belief, but even so, the findings offer an undeniably intriguing signpost to further exploration. Marchant synthesizes the research, its criticism, and its broader implications:

In a study of 50 people with advanced lung cancer, those judged by their doctors to have high “spiritual faith” responded better to chemotherapy and survived longer. More than 40 percent were still alive after three years, compared with less than 10 percent of those judged to have little faith. Are your hackles rising? You’re not alone. Of all the research into the healing potential of thoughts and beliefs, studies into the effects of religion are the most controversial.

In a study of 50 people with advanced lung cancer, those judged by their doctors to have high “spiritual faith” responded better to chemotherapy and survived longer. More than 40 percent were still alive after three years, compared with less than 10 percent of those judged to have little faith. Are your hackles rising? You’re not alone. Of all the research into the healing potential of thoughts and beliefs, studies into the effects of religion are the most controversial.

Critics of these studies … point out that many of them don’t adequately tease out other factors. For instance, religious people often have lower-risk lifestyles and churchgoers tend to enjoy strong social support, and seriously ill people are less likely to attend church.

[…]

Others think that what really matters is having a sense of purpose in life, whatever it might be. Having an idea of why you are here and what is important increases our sense of control over events, rendering them less stressful. In Saron’s three-month meditation study, the increase in levels of the enzyme that repairs telomeres correlated with an increased sense of control and an increased sense of purpose in life. In fact, Saron argues, this psychological shift may have been more important than the meditation itself. He points out that the participants were already keen meditators, so the study gave them the chance to spend three months doing something important to them. Spending more time doing what you love, whether it’s gardening or voluntary work, might have a similar effect on health. The big news from the study, Saron says, is “the profound impact of having the opportunity to live your life in a way that you find meaningful.”

Philosopher Daniel Dennett was right all along in asserting that the secret of happiness is to "find something more important than you are and dedicate your life to it."

Each of the essays in Nothing: Surprising Insights Everywhere from Zero to Oblivion is nothing short of fascinating. Complement them with theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss on the science of "something" and "nothing."

:: MORE / SHARE ::

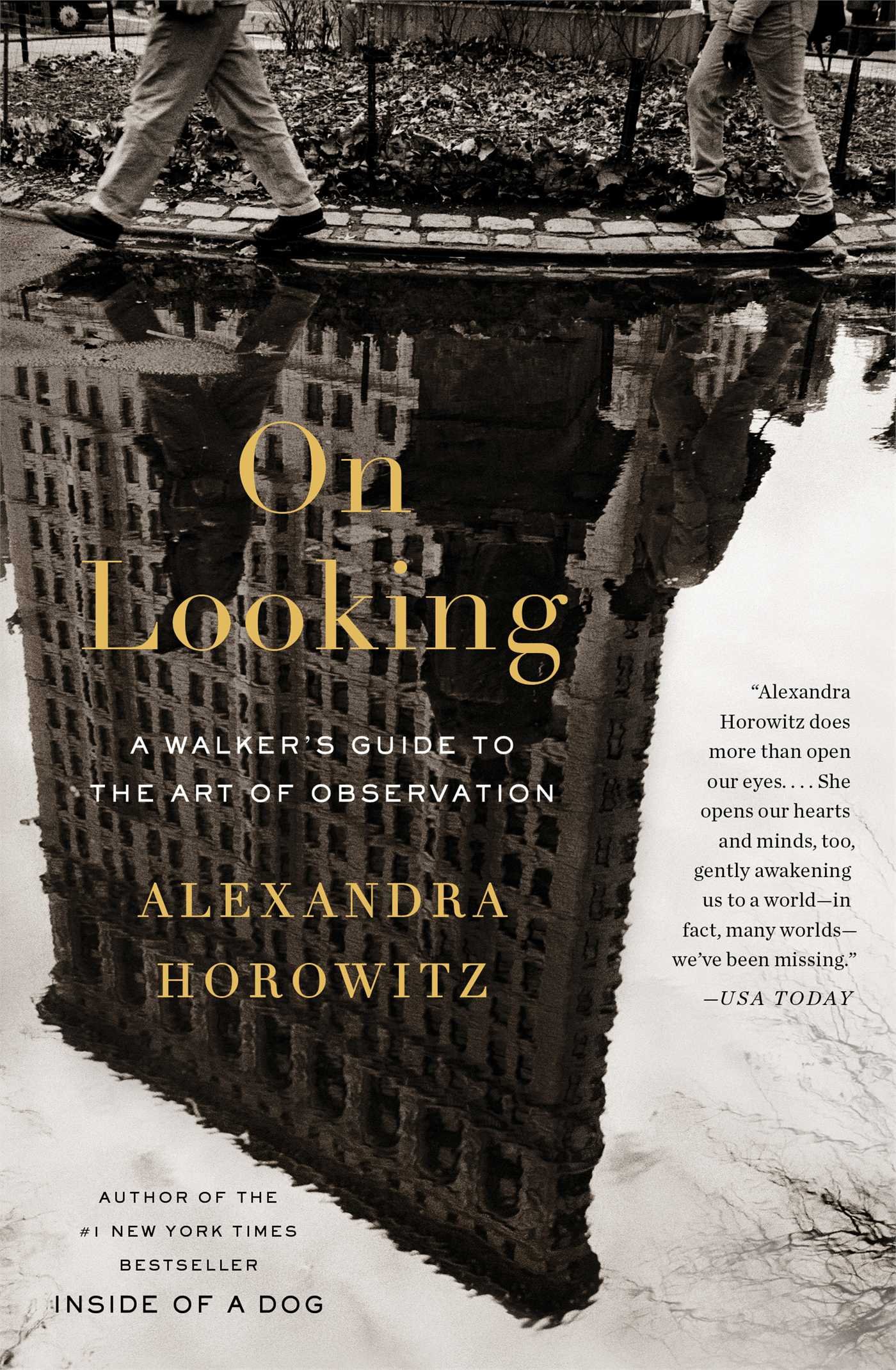

For my book club collaboration with The Dish, Andrew Sullivan's online oasis of intelligence and idealism, I had the pleasure of sitting down with cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz to discuss her immeasurably wonderful On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes (public library) – one of the best books of 2013 and among the most interesting I've ever read, a provocative exploration of how powerfully our experience of "reality" is framed by the limitations of our attention and sensory awareness.

For my book club collaboration with The Dish, Andrew Sullivan's online oasis of intelligence and idealism, I had the pleasure of sitting down with cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz to discuss her immeasurably wonderful On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes (public library) – one of the best books of 2013 and among the most interesting I've ever read, a provocative exploration of how powerfully our experience of "reality" is framed by the limitations of our attention and sensory awareness.

Our conversation ranges from Alice in Wonderland to John Cage to Susan Sontag, by way of dog cognition and productivity, in the service of understanding how different minds expose the many everyday wonderlands hidden before our eyes. Highlights below – please enjoy.

On the idea that everything is interesting if you look closer:

When you look closely at anything familiar, it kind of transmogrifies into something unfamiliar – the sort of cognitive version of saying your name again and again and again, or a word again and again and again, and getting a different sound of it after you've repeated it forty times.

When you look closely at anything familiar, it kind of transmogrifies into something unfamiliar – the sort of cognitive version of saying your name again and again and again, or a word again and again and again, and getting a different sound of it after you've repeated it forty times.

On the notion that "a writer is a professional observer":

I am, professionally, an observer of animals – by which I mean nonhuman animals. I actually have been less interested in looking at people… But of course, as it turns out, the human animal is also infinitely more complex than I give us credit for. And I appreciated – a lot – the fact that, at the end of this book, I could take a walk with anybody – it didn't have to be an expert… – and I became more appreciative of anyone's perspective. If you can just get somebody to talk about what they see when they're walking down the street, they will almost inevitably be seeing something different than you. Because they are a different person, and there's a whole background there. And, actually, I think that is a kind of writerly trick – it's sitting in the restaurant and making up stories about the people who sit around you… being interested in [them] and being able to imagine, backwards, their stories.

I am, professionally, an observer of animals – by which I mean nonhuman animals. I actually have been less interested in looking at people… But of course, as it turns out, the human animal is also infinitely more complex than I give us credit for. And I appreciated – a lot – the fact that, at the end of this book, I could take a walk with anybody – it didn't have to be an expert… – and I became more appreciative of anyone's perspective. If you can just get somebody to talk about what they see when they're walking down the street, they will almost inevitably be seeing something different than you. Because they are a different person, and there's a whole background there. And, actually, I think that is a kind of writerly trick – it's sitting in the restaurant and making up stories about the people who sit around you… being interested in [them] and being able to imagine, backwards, their stories.

On the parallels between Horowitz's book and mindfulness meditation, and the urgency of her overarching message in a culture that often, to our detriment, prioritizes productivity over presence as a form of toxic modern self-hypnosis:

I am not encouraging productivity – and I don't mind that that's the case. I value the moments in my life that are productive, certainly, but only the ones that are productive and also present. Writing the book was "productive," literally – it was a product; it was also an enjoyable engagement in the present. So it doesn't have to be either-or.

I am not encouraging productivity – and I don't mind that that's the case. I value the moments in my life that are productive, certainly, but only the ones that are productive and also present. Writing the book was "productive," literally – it was a product; it was also an enjoyable engagement in the present. So it doesn't have to be either-or.

But [I have also] spent time in a job where you then wonder, a year later, what happened to that year. And if I had bothered to sit on the subway, commuting to my office, looking – looking – I think that those moments would have been memorialized, and I would know what happened to that year…

I don't mean to be testifying against productivity per se, but I do see that it's certainly mindless, the way that we approach there being only one route to living one's life. And it is within us, this capacity to alter that – at any moment, even within that framework – to change your state.

Horowitz turns the table on the productivity question:

MP: What's interesting about the productivity dogma is that we live in a culture where we worship work ethic – by a very narrow definition – as some sort of this grand virtue. And we define it as showing up, day after day after day. But I often think that that's the surest way to lull ourselves into a kind of trance of passivity, where we show up but we're absent from our own lives. And I think one of the most beautiful things you do is you show how we can be present in our own lives, through these eleven different people and their perspectives.

MP: What's interesting about the productivity dogma is that we live in a culture where we worship work ethic – by a very narrow definition – as some sort of this grand virtue. And we define it as showing up, day after day after day. But I often think that that's the surest way to lull ourselves into a kind of trance of passivity, where we show up but we're absent from our own lives. And I think one of the most beautiful things you do is you show how we can be present in our own lives, through these eleven different people and their perspectives.

AH: Thank you. You know, you are thought of as being, probably, an excessively productive person – again, in that literal sense. You have such a fertile mind – would you say you are not productive? Or, how do you achieve your productivity?

MP: I think productivity, as we define it, is flawed to begin with, because it equates a process with a product. So, our purpose is to produce – as opposed to, our purpose is to understand and have the byproduct of that understanding be the "product." For me, I read, and I hunger to know… I record, around that, my experience of understanding the world and understanding what it means to live a good life, to live a full life. Anything that I write is a byproduct of that – but that's not the objective. So, even if it may have the appearance of "producing" something on a regular basis, it's really about taking in, and what I put out is just … the byproduct.

AH: Right. When I went on these walks, I didn't know what I would get. That was important, also.

MP: It's kind of like going down the rabbit hole but digging it in the process, too.

On Looking is an absolutely magnificent, mind-expanding, spiritually enriching read – sample it here and here. You can follow the Dish book club here and join me in supporting The Dish which, like Brain Pickings, is ad-free and supported by readers.

:: FULL ARTICLE / SHARE ::

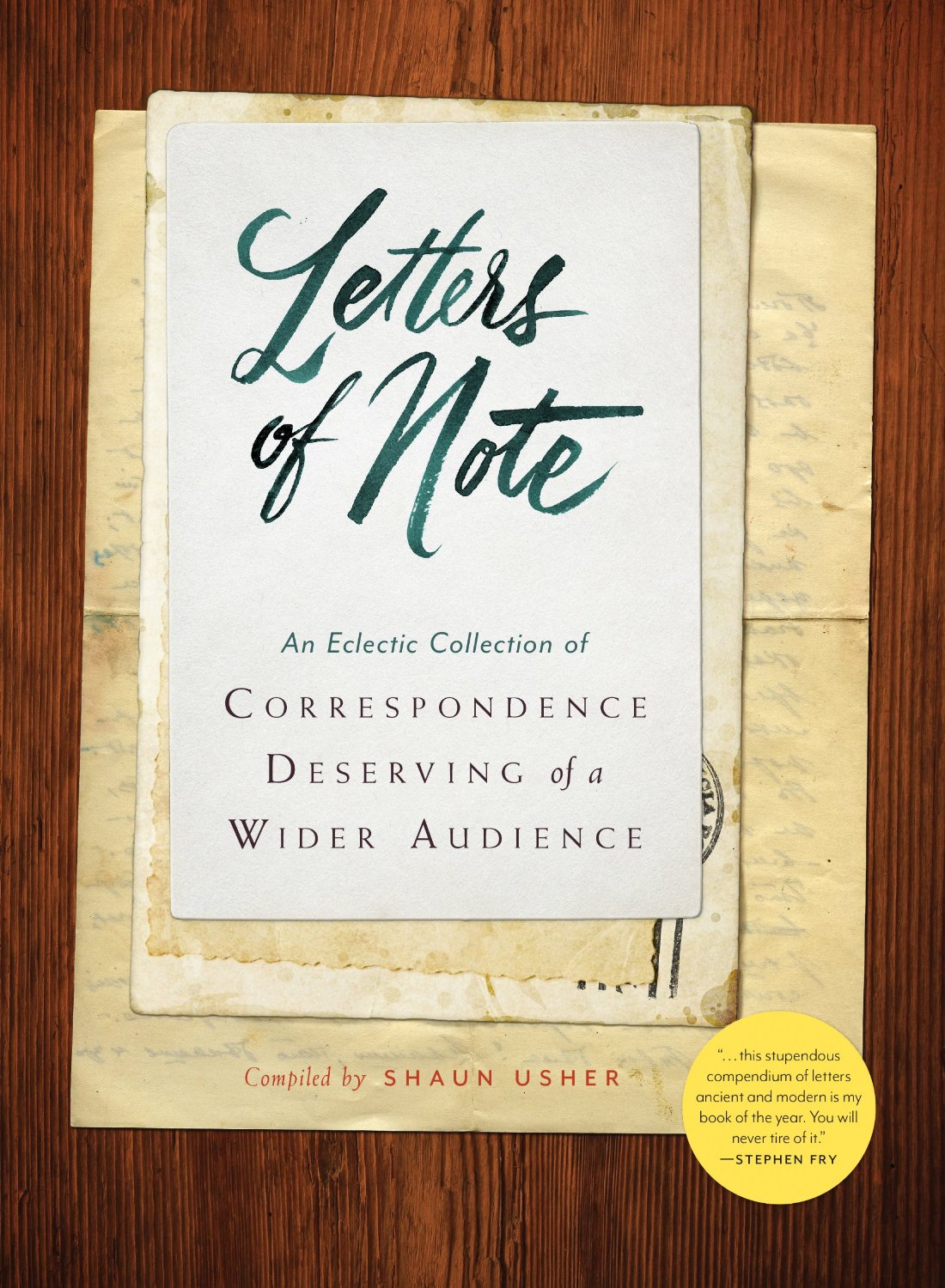

In early June of 1993, several months before cancer took his life at the age of thirty-two, beloved comedian Bill Hicks received a letter from a priest, bemoaning the "blasphemous" content in Hicks's live television special Revelations and reprimanding British broadcaster Channel 4 for having put it on the air. Writing a mere eight days before his fatal pancreatic cancer diagnosis – a young man still oblivious to his imminent tragic fate – Hicks decided to respond to the missive personally, in what became one of the most lucid and beautiful defenses of the freedom of speech ever articulated, on par with Voltaire's piercing admonition about censorship and Madeleine L'Engle's timeless words on the subject.

In early June of 1993, several months before cancer took his life at the age of thirty-two, beloved comedian Bill Hicks received a letter from a priest, bemoaning the "blasphemous" content in Hicks's live television special Revelations and reprimanding British broadcaster Channel 4 for having put it on the air. Writing a mere eight days before his fatal pancreatic cancer diagnosis – a young man still oblivious to his imminent tragic fate – Hicks decided to respond to the missive personally, in what became one of the most lucid and beautiful defenses of the freedom of speech ever articulated, on par with Voltaire's piercing admonition about censorship and Madeleine L'Engle's timeless words on the subject.

From Letters of Note: Correspondence Deserving of a Wider Audience (public library) – the same wonderful compendium by Shaun Usher that gave us young Hunter S. Thompson on how to live a meaningful life, E.B. White's heartening response to a man who had lost faith in humanity, and Eudora Welty's impossibly charming lesson in how to apply to your dream job – comes Hicks's brilliant, thoughtful, and immeasurably important response.

Hicks writes:

Dear Sir,

Dear Sir,

After reading your letter expressing your concerns regarding my special ‘Revelations’, I felt duty-bound to respond to you myself in hopes of clarifying my position on the points you brought up, and perhaps enlighten you as to who I really am. Where I come from – America – there exists this wacky concept called ‘freedom of speech’, which many people feel is one of the paramount achievements in mankind’s mental development. I myself am a strong supporter of the ‘Right of freedom of speech’, as I’m sure most people would be if they truly understood the concept. ‘Freedom of speech’ means you support the right of people to say exactly those ideas which you do not agree with. (Otherwise, you don’t believe in ‘freedom of speech’, but rather only those ideas which you believe to be acceptably stated.) Seeing as how there are so many different beliefs in the world, and as it would be virtually impossible for all of us to agree on any one belief, you may begin to realize just how important an idea like ‘freedom of speech’ really is. The idea basically states ‘while I don’t agree or care for what you are saying, I do support your right to say it, for herein lies true freedom.

It's worth pausing here to note that in the DNA of the Christian Church, as an institution, is a compulsion to do precisely the opposite – to suppress the views that contradict its dogmas. One need only look to Galileo's trails to appreciate how far back and how deeply these foundations of power-maintenance through censorship run. (But, of course, there's always Flannery O'Connor to clarify the difference between dogmatic religion and faith.)

With his characteristic blend of snark and keen cultural insight, Hicks continues:

While I’ve found many of the religious shows I’ve viewed over the years not to be to my liking, or in line with my own beliefs, I’ve never considered it my place to exert any greater type of censorship than changing the channel, or better yet – turning off the TV completely.

While I’ve found many of the religious shows I’ve viewed over the years not to be to my liking, or in line with my own beliefs, I’ve never considered it my place to exert any greater type of censorship than changing the channel, or better yet – turning off the TV completely.

Hicks moves on to the part of the letter that disturbed him the most:

In support of your position of outrage, you posit the hypothetical scenario regarding the possibly ‘angry’ reaction of Muslims to material they might find similarly offensive. Here is my question to you: Are you tacitly condoning the violent terrorism of a handful of thugs to whom the idea of ‘freedom of speech’ and tolerance is perhaps as foreign as Christ’s message itself? If you are somehow implying that their intolerance to contrary beliefs is justifiable, admirable, or perhaps even preferable to one of acceptance and forgiveness, then I wonder what your true beliefs really are.

In support of your position of outrage, you posit the hypothetical scenario regarding the possibly ‘angry’ reaction of Muslims to material they might find similarly offensive. Here is my question to you: Are you tacitly condoning the violent terrorism of a handful of thugs to whom the idea of ‘freedom of speech’ and tolerance is perhaps as foreign as Christ’s message itself? If you are somehow implying that their intolerance to contrary beliefs is justifiable, admirable, or perhaps even preferable to one of acceptance and forgiveness, then I wonder what your true beliefs really are.

If you had watched my entire show, you would have noticed in my summation of my beliefs the fervent plea to the governments of the world to spend less money on the machinery of war, and more on feeding, clothing, and educating the poor and needy of the world … A not-so-unchristian sentiment at that!

Ultimately, the message in my material is a call for understanding rather than ignorance, peace rather than war, forgiveness rather than condemnation, and love rather than fear. While this message may have understandably been lost on your ears (due to my presentation), I assure you the thousands of people I played to in my tours of the United Kingdom got it.

Whether or not the priest himself got it, even after the letter, is another story open for speculation.

Letters of Note is a spectacular collection in its entirety, featuring opinionated, vulnerable, beautiful, blunt, and deeply human contributions from such luminaries as Virginia Woolf, Roald Dahl, Richard Feynman, Jack Kerouac, Emily Dickinson, Flannery O'Connor, Leonardo da Vinci, and more. Sample three of my favorites here, here, and here. Usher continues to dig up even more gems and to share them on Letters of Note, one of the most wonderful corners of the internet.

You can watch Hicks's Revelations below. It, along with the rest of his legacy, can be found on this essential collection of his work.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

At a recent event from the New York Public Library's wonderful LIVE from the NYPL series, interviewer extraordinaire Paul Holdengräber sat down with Malcolm Gladwell – author of such bestselling books as The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (public library), Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (public library), Outliers: The Story of Success (public library), and his most recent, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants (public library) – to reflect on his career, discuss the aspects of culture that invigorate him with creative restlessness, and update his 7-word autobiography.

At a recent event from the New York Public Library's wonderful LIVE from the NYPL series, interviewer extraordinaire Paul Holdengräber sat down with Malcolm Gladwell – author of such bestselling books as The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (public library), Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (public library), Outliers: The Story of Success (public library), and his most recent, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants (public library) – to reflect on his career, discuss the aspects of culture that invigorate him with creative restlessness, and update his 7-word autobiography.

The entire conversation, embedded below, is well worth the time – there's something rather magical about witnessing two minds of great intellect collide with great humanity – but three of Gladwell's points gave me particular pause. Excerpts and transcribed highlights below.

Gladwell offers a brilliant and increasingly urgent criticism of contemporary criticism – a form of discourse that, at its best, is an increasingly rare art and, at its worst, breeds a vicious cycle of compulsive people-pleasing as a futile defense against hateful trolling:

Criticism is a privilege that you earn – it shouldn't be your opening move in an interaction… The notion that the only way you can critically engage with a person's ideas is to take a shot at them, is to be openly critical – this is actually nonsense. Some of the most effective ways in which you deal with someone's idea are to treat them completely at face value, and with an enormous amount of respect. That's actually a faster way to engage with what they're getting at than to lob grenades in their direction…

Criticism is a privilege that you earn – it shouldn't be your opening move in an interaction… The notion that the only way you can critically engage with a person's ideas is to take a shot at them, is to be openly critical – this is actually nonsense. Some of the most effective ways in which you deal with someone's idea are to treat them completely at face value, and with an enormous amount of respect. That's actually a faster way to engage with what they're getting at than to lob grenades in their direction…

If you're going to hold someone to what they believe, make sure you accurately represent what they believe.

Gladwell echoes comedian Bill Hicks's spectacular letter on what freedom of speech really means and laments the hypocrisies of what we call "tolerance":

What we call tolerance in this country, and pat ourselves on the back for, is the lamest kind of tolerance. What we call tolerance in this country is when people who are unlike us want to be like us, and when we decide to accept someone who is not like us and wants to be like us, we pat ourselves on the back… So when gays want to be like us and get married, we finally get around and say, "Oh, isn't that courageous of me, to accept gay people for finally wanting to be like us."

What we call tolerance in this country, and pat ourselves on the back for, is the lamest kind of tolerance. What we call tolerance in this country is when people who are unlike us want to be like us, and when we decide to accept someone who is not like us and wants to be like us, we pat ourselves on the back… So when gays want to be like us and get married, we finally get around and say, "Oh, isn't that courageous of me, to accept gay people for finally wanting to be like us."

Sorry – you don't get points for accepting someone who wants to be just like you. You get points for accepting someone who doesn't want to be like you – that's where the difficulty lies.

But perhaps Gladwell's most culturally important point – and I say this as someone who ardently advocates for the uncomfortable luxury of changing one's mind – has to do with the tyranny of our irrationally immovable opinions:

I feel I change my mind all the time. And I sort of feel that's your responsibility as a person, as a human being – to constantly be updating your positions on as many things as possible. And if you don't contradict yourself on a regular basis, then you're not thinking.

I feel I change my mind all the time. And I sort of feel that's your responsibility as a person, as a human being – to constantly be updating your positions on as many things as possible. And if you don't contradict yourself on a regular basis, then you're not thinking.

[…]

If you create a system where you make it impossible, politically, for people to change [their] mind, then you're in trouble.

See the full conversation below, find Gladwell's books here and help support The New York Public Library's wonderful programming here.

:: LISTEN / SHARE ::

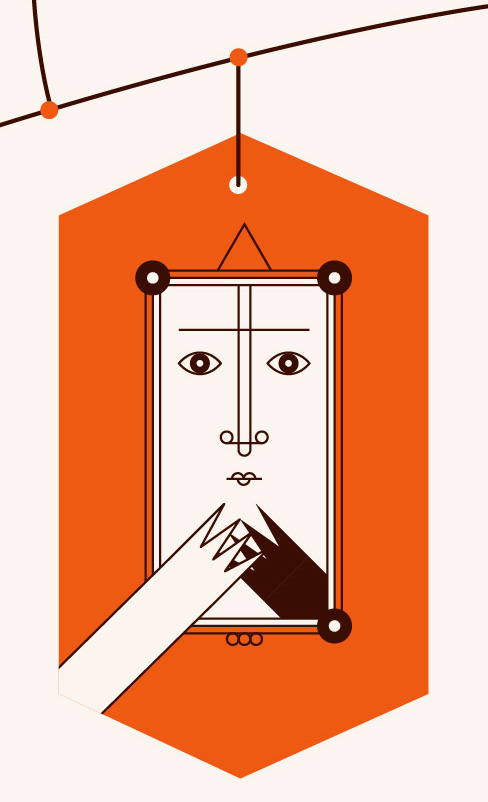

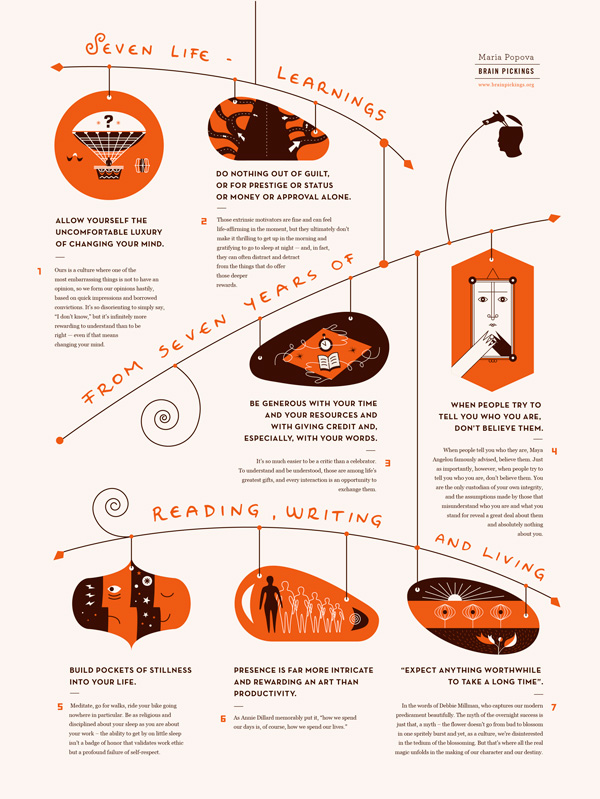

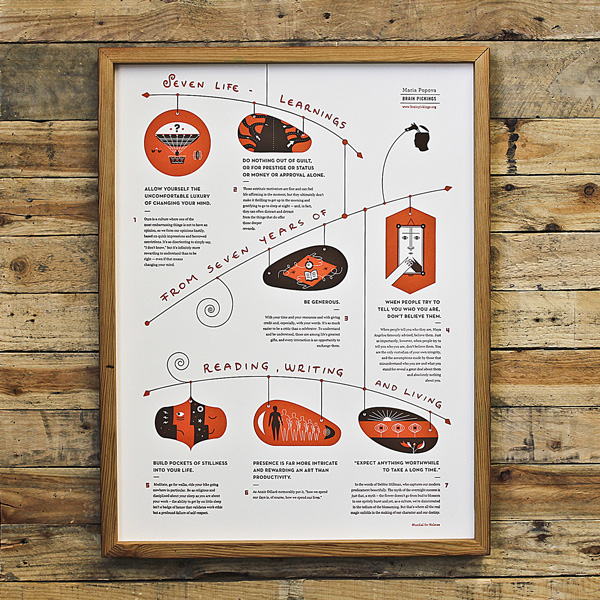

In the fall of 2013, as Brain Pickings was turning seven, I wrote about the seven most important things I learned in those seven years of reading, writing, and living. Much to my surprise and humbling delight, I began receiving a steady outpour of letters from readers, people for whom these notes to myself had struck a deep chord of resonance in their own lives, on their own journeys.

In the fall of 2013, as Brain Pickings was turning seven, I wrote about the seven most important things I learned in those seven years of reading, writing, and living. Much to my surprise and humbling delight, I began receiving a steady outpour of letters from readers, people for whom these notes to myself had struck a deep chord of resonance in their own lives, on their own journeys.

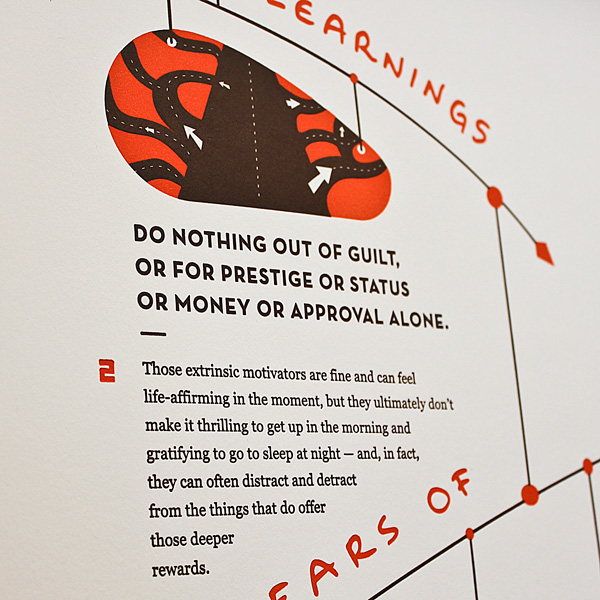

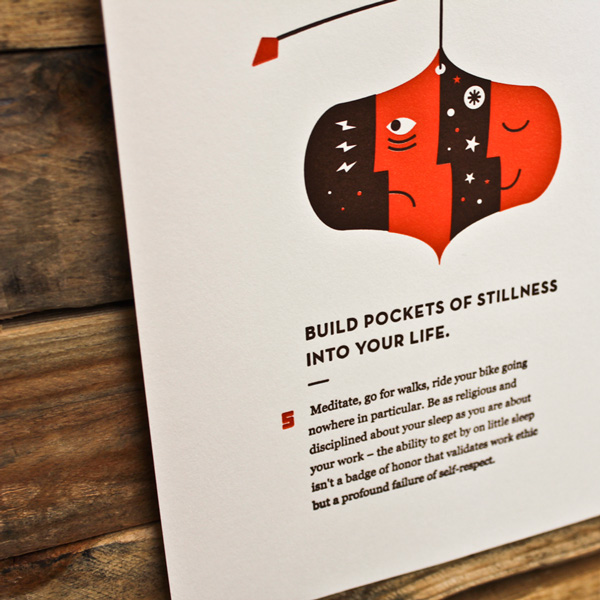

Eventually, my friends at Holstee – makers of the beloved Holstee Manifesto – reached out and suggested a creative collaboration that would bring these seven learnings to life in visual form. Having known the Holstee crew for many years, and having long shared an enormous kinship of spirit and values with them, I was instantly in. We worked with Uruguayan illustrator and graphic designer Martin Azambuja, who came up with the visual metaphor of a mobile for an added layer of symbolism.

I'm proud and so very excited to reveal the end result of this collaborative labor of love, months in the making – an 18"x24" letterpress poster printed on thick, sustainable cotton paper, inspired by vintage children's book illustration and mid-century graphic design.

Read the original article here and grab a print here.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, please consider helping with a small donation.