Jul 30, 2018 09:17 am

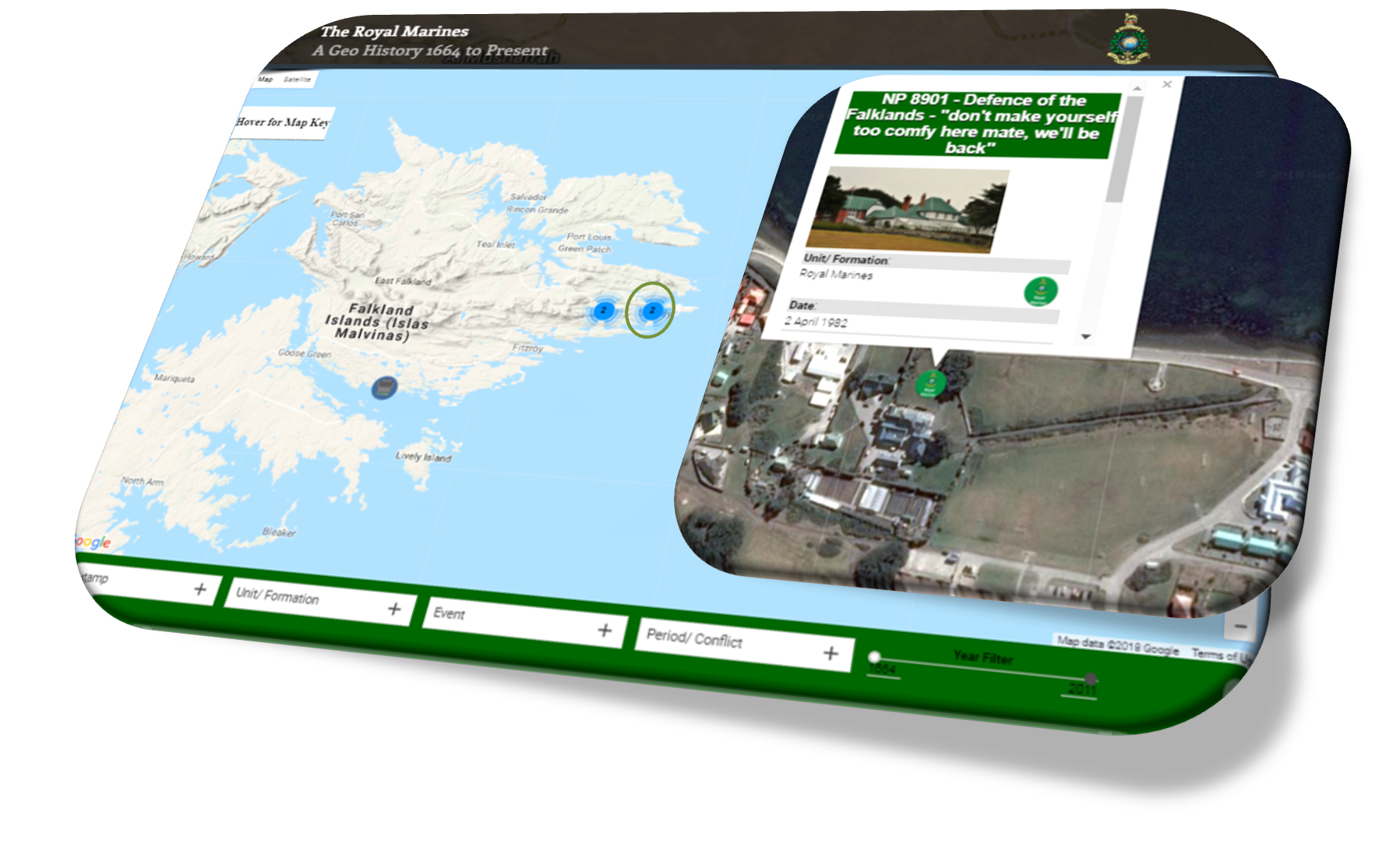

The Royal Marines - A Geo History 1664 to Present The Globe & Laurel March/April 2018 by Simon Biggs Even before I was a young Marine in training I remember seeing a poster that showed the Corps on Operations across the world throughout the Cold War period with one famous year where it showed a tropical beach, it said that this year the Royal Marines took a holiday! We all know that we have a long and varied history and that the Globe in our crest represents the fact that Marines really have been busy projecting power since 1664 and have fought in every dark corner and every climate imaginable.  My project is to bring some of these moments alive, and to put in context the considerable effect the Royal Marines have had globally by mapping some of the key historic moments from the raising of the Maritime Regiment to our present-day Commando role. This includes early actions in the 16 and 1700's both onboard and ashore as the country expanded its influence overseas, trading, colonising and warring and later the Royal Marines’ significant and often forgotten contribution to the wars of the 1800's in Europe and America, often at the vanguard of Empire.  Finally, to the last 118 years of modern military history manning turrets on Ironclads, the First World War and later Combined Operations and Commando actions in Europe, the Far East and Korea, our withdrawal from Empire, counter insurgency in Malaya, Palestine and Borneo, and modern war fighting from the Falklands to Iraq and Afghanistan. Through my research I have discovered many interesting facts, for example the amphibious assault in Egypt where the Marines charged the French so repeatedly and with such determination and gallantry that they earned for themselves the cognomen of ‘The Bulldogs of the Army’ only 130 miles from Port Said where 45 Cdo RM would carry out the world’s first Heli-borne assault 150 years later.  I have also started to pin selected memorials erected to units and individuals, some forgotten except by a very few, for example the memorial on a desert road in Kuwait to eight members of 3 Cdo Bde and four US servicemen onboard the CH46 killed deploying into Iraq in 2003 and the small bridge named after a young Army Medic attached to 45 Cdo Gp RM and posthumously awarded the VC for saving the lives of many of his troop under fire before being fatally wounded himself.  I am lucky enough to have visited both of these memorials in the past and mapping them for others to see has been an honour. I hope to inspire those interested in our Corps and its history and provide a reference that is easy to use and helps to visualise the true extent of the Royal Marines footprint over the last 354 years. For more information please contact me via my website or e mail sibiggs539@hotmail.com Originally published in The Globe & Laurel March/April 2018

Read in browser »

Jul 27, 2018 08:13 am

Hannah Snell was born in Worcester, England on 23 April 1723. Locals claim that she played a soldier even as a child. In 1740, she moved to London and married James Summes on 18 January 1744. She named herself Bob Corigan so she could fight.  In 1746, she gave birth to a daughter, Susannah, who died a year later. Snell borrowed a male suit from her brother-in-law James Gray, assumed his name, and began to search for Summes, who had abandoned her while she was pregnant with his child.[1] She later learned that her husband had been executed for murder. According to her account, she joined John Guise's regiment, the 6th Regiment of Foot, in the army of the Duke of Cumberland against Bonnie Prince Charlie, and deserted when her sergeant gave her 500 lashes. However, the chronology of her life makes it very unlikely that she ever served in Guise's regiment and this part of the story is likely to have been a fabrication. Following the death of her daughter, she moved to Portsmouth and joined the Marines. She boarded the ship Swallow at Portsmouth on 23 October 1747. The ship sailed to Lisbon on 1 November. Her unit was about to invade Mauritius, but the attack was called off. Her unit then sailed to India.  In August 1748, her unit was sent to an expedition to capture the French colony of Pondicherry in India. Later, she also fought in the battle in Devicottail in June 1749. She was wounded eleven times to the legs. She was also shot in her groin and to avoid revealing her gender, she instructed a local woman to take out the bullet instead of being tended by the regimental surgeon. In 1750, her unit returned to Britain and traveled from Portsmouth to London, where she revealed her sex to her shipmates on 2 June. She petitioned the Duke of Cumberland, the head of the army, for her pension. She also sold her story to London publisher Robert Walker, who published her account, The Female Soldier, in two different editions. She also began to appear on stage in her uniform presenting military drills and singing songs.  Three painters painted her portrait in her uniform and The Gentleman's Magazine reported her claims. She was honorably discharged and the Royal Hospital, Chelsea officially recognized Snell's military service in November and granted her a pension in 1750 (increased in 1785), a rare thing in those days.  Hannah retired to Wapping and began to keep a pub named The Female Warrior (or The Widow in Masquerade, accounts disagree) but it did not last long. By the mid-1750s, she was living in Newbury in Berkshire. In 1759, she married Richard Eyles there, with whom she had two children. In 1772, she married Richard Habgood of Welford, also in Berkshire, and the two moved to the Midlands. In 1785, she was living with her son George Spence Eyles, a clerk, on Church Street, Stoke Newington. Gentleman's Magazine article about Snell. Wood engraving, 1750. In 1791 her mental condition suddenly worsened. She was admitted to Bethlem Hospital on 20 August. She died on 8 February 1792.

Read in browser »

Jul 26, 2018 05:31 am

The Royal Marines Charity Mission is to provide the best possible through life charitable support for Royal Marines, their families, veterans and cadets The Royal Marines Charity exists to help the entire Royal Marines family. Strong believers in once a Marine, always a Marine. The Charity offers a range of services to both serving and veterans. If you need help, The Royal Marines Charity is here for you. From financial assistance to advice on finding a second, meaningful career. Follow on Twitter @theRMcharity

Read in browser »

Jul 25, 2018 06:43 am

On July 24, the allied fleet arrived outside Gibraltar. In all, Rooke commanded 16 English ships under Byng and six Dutch ships under Rear Admiral Paulus van der Dussen. The ships positioned themselves inside the harbor, carefully out of range of the bastion’s guns. Rooke directed matters from his flagship, Royal Katherine, at the entrance to the bay. Beginning with a brief covering barrage laid down by the guns of his fleet, Rooke launched an amphibious assault by 1,900 English and 400 Dutch marines.  Their initial objectives were the main shore defenses, the Old and New Moles, and the fortified Teurto Tower.From 500 yards out to sea, the attackers (soldiers with muskets and swords and sailors armed with cutlasses, boarding pikes, and pistols) clambered down from their transport vessels onto a variety of launches, ships boats, skiffs, and barges to make their approach to the objectives. Small cannons were also made ready to be sent ashore if needed. It was the first time that Rooke’s floating armada had conducted an amphibious assault and the largest one ever attempted by an English force up to that time. Within an hour after setting off from the mother ships, the invaders landed on the sandy isthmus at the northern end of the Gibraltar peninsula. After forming into columns and advancing a short distance to attack the New Mole Fort, the English were struck by a devastating setback. Either a mine was set off by the defenders or else a powder magazine accidentally detonated—no one could determine which—and the assaulting force was wracked by a powerful explosion that killed or wounded 100 attackers.  Immediately after the deafening blast occurred, the surviving members of the landing party froze in their tracks, looking in shocked amazement at the loss of life and the wretched condition of the ground caused by the unexpected event. Unsure whether it was safe to carry on the attack, some of the men fell to the earth seeking shelter, while others ran back toward the landing boats. But most of the attackers simply remained stationary and silent. Those officers who remained alive and unhurt, along with hard-bitten sergeants and corporals, rapidly regained their senses and hurried to calm the men and put them back into some sort of formation. As the English marines regained their composure and prepared to continue the advance, reinforcements came ashore. Soon the reorganized English-Dutch force headed for the fort. Encircling the installation and discharging their firearms, the allies stormed and took the place. Two columns of men were dispatched to surround the town. Meanwhile, sailors from the fleet secured the surrounding heights. They had been selected for the task because of the agility and speed with which they normally performed their shipboard duties. Soon the Spanish defenders began displaying white flags signaling their desire to surrender.  In 1827, the battle honours of the Royal Marines being so numerous (109 at this point), King George IV directed that the “Great Globe” itself should form their cap badge and that the single battle honour “Gibraltar” be selected as representative of all the others worn by the Corps. “Gibraltar” remains today the sole battle honour shown on the Regimental Colours of the Royal Marines.

Read in browser »

Jul 18, 2018 06:54 am

Throughout the Second World War, LCAs were used for landing Allied forces in almost every Commando operation, major and minor, in the European theatre. They also saw service in North Africa and the Indian Ocean. The first four LCAs used in an opposed landing disembarked 120 French Foreign Legionnaires of the 13th Demi-Brigade (13e DBLE) on the beach at Bjerkvik, 8 miles (13 km) above Narvik, on 13 May during the Norwegian Campaign, perhaps the last operational use of LCAs by the Royal Navy was in 1967 when boats from HMS Albion supported operations in Aden; an LCA being the last craft to carry British personnel away from Aden.  Landing Craft Assault (LCA) was a landing craft used extensively in World War II. Its primary purpose was to ferry troops from transport ships to attack enemy-held shores. The craft derived from a prototype designed by John I. Thornycroft Ltd. of Woolston, Hampshire, UK. During the war it was manufactured throughout the United Kingdom in places as various as small boatyards and furniture manufacturers.  When a new amphibious assualt craft was envisaged a maritime architect Mr. Fleming of Liverpool was proposed by the Board of Trade to vivst the Inter-Service Training and Development Centre (ISTDC) at Fort Cumberland and the design of the first LCA began, the concept was for the vessel to be built of Birmabright, an aluminium alloy. A meeting with the Director of Naval Construction (DNC) was convened to discuss the results and due to some reservations DNC asked ISTDC to give their specifications to three other firms so that they could also submit designs. Two of the firms were unable to tender, the third, Messrs Thornycroft, had a proposal on the drawing board in forty-eight hours and ISTDC and the DNC agreed that construction of a prototype should be paid for. The craft might be constructed for experimental purposes on the understanding that the DNC held no responsibility. Two craft were brought down to Langstone Harbour for competitive trials. On its trials on a misty morning, the noise from the two 120 hp Chryslers in the Birmabright alloy hull scared some mothers who hurried their children away from the Isle of Wight beaches as the craft came inshore.  A platoon of Royal Marines disembarked from the Fleming craft in a quarter of the time taken by the platoon in the Thornycroft, the silhouette of the Fleming craft was less, it created less disturbance when steaming, and it beached better. But, and this was later the deciding factor, the Birmabright craft was so noisy that it meant sacrificing tactical surprise, while it was impossible to mount armour on its sides. The failings of the Thornycroft craft on the other hand could all be overcome. A second prototype from Thornycroft had a double-diagonal mahogany hull with twin engines and those features — low silhouette, quiet engines, little bow wave — which appealed to the Centre's staff in their search for a craft that could make surprise landings. The craft beached satisfactorily, a quality retained in all LCA designs, but the troops took too long to disembark across this prototype's narrow ramp. Armour could easily take the place of the outer mahogany planking, the exit could be lowered, the silhouette could be cut down and the engines could be so silenced that they would not be heard at twenty-five yards. So although the Fleming boat won at the trial, it was the Thornycroft design, duly altered, that became the assault landing craft. In the 42 months prior to the end of 1944 Britain was able to produce an additional 1,694 LCAs, by the time production was in full tilt in preparation for Operation Overlord production rose to sixty LCAs a month.  The LCA's crew of four included a Sternsheetsman, whose action station was at the stern to assist in lowering and raising the boat at the davits of the Landing Ship Infantry (LSI), a Bowman-gunner, whose action station was at the front of the boat to open and close the armoured doors, raise and lower the ramp, and operate the one or two Lewis guns in the armoured gun shelter opposite the steering position, a stoker-mechanic responsible for the engine compartment, and a Coxswain who sat in the armoured steering shelter forward on the starboard side. Though in control of the rudders, the coxswain did not have direct control of the engines and gave instructions to the stoker through voicepipe and telegraph. In July 1943 Royal Marines from the Mobile Naval Bases Defence Organization and other shore units were drafted into the pool to crew the expanding numbers of landing craft being gathered in England for the Normandy invasion. By 1944, 500 Royal Marine officers and 12,500 Marines had become landing craft crew. By 1945, personnel priorities had changed once more. Marines of landing craft flotillas were formed into two infantry brigades to address the manpower shortage in ending the war in Germany. A junior naval or Royal Marine officer commanded three LCAs and was carried aboard one of the craft. The officer relayed signals and orders to the other two craft in the group by signal flags in the earlier part of the war, but by 1944 many of the boats had been fitted with two-way radios. On the wave leader's boat the Sternsheetsman was normally employed as the Signalman but flags, Aldis lamps, and loudhailers were sometimes more reliable than 1940s radio equipment.  Normally, a flotilla comprised 12 boats at full complement, though this number was not rigid. The flotilla's size could alter to fit operational requirements or the hoisting capacity of a particular LSI. An infantry company would be carried in six LCAs. A flotilla was normally assigned to an LSI. These varied in capacity with smaller ones, such as the 3,975+ ton HMCS Prince David able to hoist 6 LCAs, and larger ones, such as the nearly 16,000 ton HMS Glengyle with room for 13 LCAs. Throughout World War II, LCAs travelled under their own power, towed by larger craft, or on the davits of LSIs or Landing Ship, Tank (LSTs). In larger operations such as Jubilee, Torch, Husky, and Overlord, LCAs were carried to invasion areas by Landing Ship Infantry (LSI). The location chosen for the LSI to stop and lower the LCA was a designated point inside the 'Transport Area' when the LSI was operating with a US Navy Task Force, or the 'Lowering Position' when with a Royal Navy Task Force. The transport area or lowering position was approximately 6–11 miles off shore (11 miles was amphibious doctrine for the USN by mid-war, while the RN tended to accept the risks associated with drawing nearer shore). The LCAs were swung down to the level of the loading decks and the crews climbed aboard. At this time the troops were assembled by platoons ready to cross gangways. When the  coxswain gave the platoon commander the word, he took his men over and into the stern of the LCA and they filed forward. The platoon divided into three lines, one for each section of the platoon, the outboard two sections sitting under the protection of the troop well's armoured decks, the centre section crouched on the low seating bench down the middle. Despite the wires holding the craft to a fender, the LCA rolled with the motion of the ship. The coxswain would then call, 'Boat manned,' to the telephone operator at the loading station, who, in turn, reported to the 'LC' Control Room. The coxswain would then warn the troops to mind the pulleys at the ends of falls fore and aft, which could wave freely about when the craft had been set in the water. The task of hooking on and casting off from the ship required skill and seamanship from the coxswain, bowman, and sternsheetsman. The snatch blocks used were heavy steel and difficult to handle. The bowman and sternsheetsman stood by his respective block, as the craft was lowered into the water. At a time when there was sufficient slack in the falls both had to cast off at the same instant, and the blocks had to be released while there was slack in the falls. If the boat was not freed at both ends at once the rise and fall of the sea could cause the boat to tip, swamp, and perhaps capsize with loss of life. Casting-off was done in all sorts of sea conditions, and the sea might be rising and falling a metre or more (6' swells were not uncommon on D-Day). A combination of skill and luck could redeem a failure to cast-off, nevertheless. On D-Day, an LCA of Royal Marine 535 Flotilla, LSI Glenearn, released all but its after falls, which were jammed, and the craft tilted alarmingly to 45 degrees. The coxswain kept his head, calming the passengers, while seamen worked to free the falls. Once free, the coxswain needed to get the LCA away to prevent colliding with the towering side of the LSI as it rose and fell with the swells. Commonly, the LCAs of a flotilla would form line-ahead behind a motor launch or Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) that would guide them to their designated beach (it was not normal for LCAs to circle the landing ship as was USN and US Coast Guard practice). As the LCA approached the beach they would form line abreast for the final run-in to the beach. When the front of the LCA came to ground on the beach it was called the 'touch down.'  Throughout the Second World War, LCAs were used for landing Allied forces in almost every Commando operation, major and minor, in the European theatre. They also saw service in North Africa and the Indian Ocean, and also saw some service in the Pacific close to the end of the war. See some of the Amphibious Operations pinned here

Read in browser »

Jul 12, 2018 07:20 am

17 June 1775: During the night of 16-17 June, the American rebels, tightening their grip on Boston, occupied and entrenched Breed’s Hill, overlooking the harbour. (Their orders specified the fortification of Bunker Hill, which was a little higher). Next day Major-General William Howe, commanding the 2,200-strong British force, counter-attacked.   He underestimated the tenacity of his opponents, and relied solely on shock action with the bayonet. Ordered to advance with unloaded muskets, the British sustained needlessly heavy losses. The Americans, behind entrenchments, rail fences and stone walls, repulsed two assaults, but their ammunition supply failed during the third assault and they were driven off the hill. 1,054 British troops were killed or wounded. Although the engagement left the local situation unchanged, the fact that the Americans had made so determined a stand against regular troops provided a boost to their morale On the left flank of the British, the houses of Charlestown were in flames. The 2nd Marine battalion took part in the Battle of Bunker Hill. Major Pitcairn was commander of the final assault on Colonel Prescott's redoubt. In the summer heat he led his Marines, including his son Thomas, (a Lieutenant aged 19), on foot up the hill for the final assault.  The Marines at the Battle of Bunker Hill - David Rowlands While advancing, they marched through another line of infantry who were being pushed back by heavy rebel fire. Pitcairn told them to "Break and let the Marines through!", and is said to have threatened to "bayonet the buggers" if they would not get out of the Marines' way!  He waved his sword and urged his men on: "Now, for the glory of the Marines!"A musket ball struck Major Pitcairn in the breast and he fell into the arms of his son Thomas. According to one story, the rebel troops were near defeat, when Major Pitcairn ordered them to surrender. An American then stepped forward and shot Pitcairn. The British were temporarily stunned, and the Americans were able to retreat. Another story tells that the major fell dead just as he was shouting to his men, “The day is ours.”Pitcairn's son carried his wounded father out of the line of fire to the water's edge, before returning to the battle. "I have lost my father!" he said. "We have all lost a father!" some of the Marines responded. A boat took Pitcairn back to Boston, where he was put to bed in a house on Prince Street. Although the bullet was removed and his wound dressed, he died a couple of hours later. He was 52. The fatal musket ball and his uniform buttons were returned to his wife and children. The Death of Major John Pitcairn - Wood Engraving As the Americans’ ammunition expired, their firing sputtered and “went out like an old candle,” wrote William Prescott, who commanded the hilltop redoubt. His men resorted to throwing rocks, then swung their muskets at the bayonet-wielding British pouring over the rampart. “Nothing could be more shocking than the carnage that followed the storming [of] this work,” wrote a royal marine. “We tumbled over the dead to get at the living,” with “soldiers stabbing some and dashing out the brains of others.” The surviving defenders fled, bringing the battle to an end. In just two hours of fighting, 1,054 British soldiers—almost half of all those engaged—had been killed or wounded, including many officers. American losses totaled over 400. The first true battle of the Revolutionary War was to prove the bloodiest of the entire conflict. Though the British had achieved their aim in capturing the hill, it was a truly Pyrrhic victory. “The success is too dearly bought,” wrote Gen. William Howe, who lost every member of his staff (as well as the bottle of wine his servant carried into battle). More here:

Read in browser »

Jul 02, 2018 05:47 am

From the Memoirs of Sir Frederick Lewis Maitland then Captain of HMS Bellerophon About ten A.M. the barge was manned, and a captain's guard turned out.  When Buonaparte came on deck, he looked at the marines, who were generally fine-looking young men, with much satisfaction; went through their ranks, inspected their arms, and admired their appearance, saying to Bertrand, "How much might be done with a hundred thousand such soldiers as these."  He asked which had been longest in the corps; went up and spoke to him. His questions were put in French, which I interpreted, as well as the man's answers. He enquired how many years he had served; on being told upwards of ten, he turned to me and said, "Is it not customary in your service, to give a man who has been in it so long some mark of distinction?" He was informed that the person in question had been a sergeant, but was reduced to the ranks for some misconduct. He then put the guard through part of their exercise, whilst I interpreted to the Captain of Marines, who did not understand French, the manoeuvres he wished to have performed.  He made some remarks upon the difference of the charge with the bayonet between our troops and the French; and found fault with our method of fixing the bayonet to the musquet, as being more easy to twist off, if seized by an enemy when in the act of charging.

Read in browser »

|