|

|

Hello <<Name>>! This is the weekly Brain Pickings newsletter by Maria Popova. If you missed last week's edition — Walt Whitman on women's centrality to democracy; stunning art from the world's first encyclopedia of deep-sea cephalopods; remembering Freeman Dyson — you can catch up right here. And if you find any value and joy in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation – I spend innumerable hours and tremendous resources on it each week, as I have been for more than thirteen years, and every little bit of support helps enormously. If you already donate: THANK YOU.

Hello <<Name>>! This is the weekly Brain Pickings newsletter by Maria Popova. If you missed last week's edition — Walt Whitman on women's centrality to democracy; stunning art from the world's first encyclopedia of deep-sea cephalopods; remembering Freeman Dyson — you can catch up right here. And if you find any value and joy in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation – I spend innumerable hours and tremendous resources on it each week, as I have been for more than thirteen years, and every little bit of support helps enormously. If you already donate: THANK YOU.

|

“I… a universe of atoms… an atom in the universe,” the Nobel-winning physicist Richard Feynman wrote in his lovely prose poem about evolution. “The fact that we are connected through space and time,” evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis observed of the interconnectedness of the universe, “shows that life is a unitary phenomenon, no matter how we express that fact.”

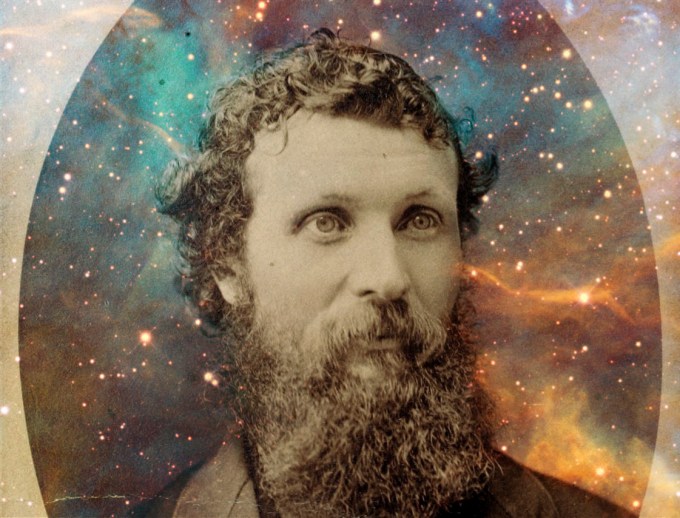

A century before Feynman and Margulis, the great Scottish-American naturalist and pioneering environmental philosopher John Muir (April 21, 1838–December 24, 1914) channeled this elemental fact of existence with uncommon poetic might in John Muir: Nature Writings (public library) — a timeless treasure I revisited in composing The Universe in Verse.

John Muir

Recounting the epiphany he had while hiking Yosemite’s Cathedral Peak for the first time in the summer of his thirtieth year — an epiphany strikingly similar to the one Virginia Woolf had at the moment she understood what it means to be an artist — Muir writes:

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. One fancies a heart like our own must be beating in every crystal and cell, and we feel like stopping to speak to the plants and animals as friendly fellow mountaineers. Nature as a poet, an enthusiastic workingman, becomes more and more visible the farther and higher we go; for the mountains are fountains — beginning places, however related to sources beyond mortal ken. When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. One fancies a heart like our own must be beating in every crystal and cell, and we feel like stopping to speak to the plants and animals as friendly fellow mountaineers. Nature as a poet, an enthusiastic workingman, becomes more and more visible the farther and higher we go; for the mountains are fountains — beginning places, however related to sources beyond mortal ken.

Later that summer, as he makes his way to Tuolumne Meadow in eastern Yosemite, Muir is reanimated with this awareness of the exquisite, poetic interconnectedness of nature, which transcends individual mortality. In a sentiment evocative of Rachel Carson’s lyrical assertion that “the lifespan of a particular plant or animal appears, not as drama complete in itself, but only as a brief interlude in a panorama of endless change,” Muir writes:

One is constantly reminded of the infinite lavishness and fertility of Nature — inexhaustible abundance amid what seems enormous waste. And yet when we look into any of her operations that lie within reach of our minds, we learn that no particle of her material is wasted or worn out. It is eternally flowing from use to use, beauty to yet higher beauty; and we soon cease to lament waste and death, and rather rejoice and exult in the imperishable, unspendable wealth of the universe, and faithfully watch and wait the reappearance of everything that melts and fades and dies about us, feeling sure that its next appearance will be better and more beautiful than the last. One is constantly reminded of the infinite lavishness and fertility of Nature — inexhaustible abundance amid what seems enormous waste. And yet when we look into any of her operations that lie within reach of our minds, we learn that no particle of her material is wasted or worn out. It is eternally flowing from use to use, beauty to yet higher beauty; and we soon cease to lament waste and death, and rather rejoice and exult in the imperishable, unspendable wealth of the universe, and faithfully watch and wait the reappearance of everything that melts and fades and dies about us, feeling sure that its next appearance will be better and more beautiful than the last.

[…]

More and more, in a place like this, we feel ourselves part of wild Nature, kin to everything.

One of Chiura Obata’s paintings of Yosemite

A year earlier, during his famous thousand-mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico, Muir recorded his observations and meditations in a notebook inscribed John Muir, Earth-Planet, Universe. In one of the entries from this notebook, the twenty-nine-year-old Muir counters the human hubris of anthropocentricity in a sentiment far ahead of his time and, in many ways, ahead of our own as we grapple with our responsibility to the natural world. More than a century before Carl Sagan reminded us that we, like all creatures, are “made of starstuff,” Muir humbles us into our proper place in the cosmic order:

The universe would be incomplete without man; but it would also be incomplete without the smallest transmicroscopic creature that dwells beyond our conceitful eyes and knowledge… The fearfully good, the orthodox, of this laborious patchwork of modern civilization cry “Heresy” on every one whose sympathies reach a single hair’s breadth beyond the boundary epidermis of our own species. Not content with taking all of earth, they also claim the celestial country as the only ones who possess the kind of souls for which that imponderable empire was planned. The universe would be incomplete without man; but it would also be incomplete without the smallest transmicroscopic creature that dwells beyond our conceitful eyes and knowledge… The fearfully good, the orthodox, of this laborious patchwork of modern civilization cry “Heresy” on every one whose sympathies reach a single hair’s breadth beyond the boundary epidermis of our own species. Not content with taking all of earth, they also claim the celestial country as the only ones who possess the kind of souls for which that imponderable empire was planned.

Long before Maya Angelou reminded us that we are creatures “traveling through casual space, past aloof stars, across the way of indifferent suns,” Muir adds:

This star, our own good earth, made many a successful journey around the heavens ere man was made, and whole kingdoms of creatures enjoyed existence and returned to dust ere man appeared to claim them. After human beings have also played their part in Creation’s plan, they too may disappear without any general burning or extraordinary commotion whatever. This star, our own good earth, made many a successful journey around the heavens ere man was made, and whole kingdoms of creatures enjoyed existence and returned to dust ere man appeared to claim them. After human beings have also played their part in Creation’s plan, they too may disappear without any general burning or extraordinary commotion whatever.

However disquieting and corrosive to the human ego such awareness may be, Muir argues that we can never be conscientious citizens of the universe unless we accept this fundamental cosmic reality. In our chronic civilizational denial of it, we are denying nature itself — we are denying, in consequence, our own humanity. A century before the inception of the modern environmental movement, he writes:

No dogma taught by the present civilization seems to form so insuperable an obstacle in the way of a right understanding of the relations which culture sustains to wildness as that which regards the world as made especially for the uses of man. Every animal, plant, and crystal controverts it in the plainest terms. Yet it is taught from century to century as something ever new and precious, and in the resulting darkness the enormous conceit is allowed to go unchallenged. No dogma taught by the present civilization seems to form so insuperable an obstacle in the way of a right understanding of the relations which culture sustains to wildness as that which regards the world as made especially for the uses of man. Every animal, plant, and crystal controverts it in the plainest terms. Yet it is taught from century to century as something ever new and precious, and in the resulting darkness the enormous conceit is allowed to go unchallenged.

I have never yet happened upon a trace of evidence that seemed to show that any one animal was ever made for another as much as it was made for itself. Not that Nature manifests any such thing as selfish isolation. In the making of every animal the presence of every other animal has been recognized. Indeed, every atom in creation may be said to be acquainted with and married to every other, but with universal union there is a division sufficient in degree for the purposes of the most intense individuality; no matter, therefore, what may be the note which any creature forms in the song of existence, it is made first for itself, then more and more remotely for all the world and worlds.

Illustration by Oliver Jeffers from Here We Are: Notes for Living on Planet Earth

This revelatory sense of interconnectedness comes over Muir again a decade later, as he journeys to British Columbia on a steamer in the spring of 1879, experiencing for the first time the otherworldly wonder and might of the open ocean. A century after William Blake saw the universe in a grain of sand, Muir writes:

The scenery of the ocean, however sublime in vast expanse, seems far less beautiful to us dry-shod animals than that of the land seen only in comparatively small patches; but when we contemplate the whole globe as one great dewdrop, striped and dotted with continents and islands, flying through space with other stars all singing and shining together as one, the whole universe appears as an infinite storm of beauty. The scenery of the ocean, however sublime in vast expanse, seems far less beautiful to us dry-shod animals than that of the land seen only in comparatively small patches; but when we contemplate the whole globe as one great dewdrop, striped and dotted with continents and islands, flying through space with other stars all singing and shining together as one, the whole universe appears as an infinite storm of beauty.

More than a century later, Muir’s complete Nature Writings remain a transcendent read. Complement this portion with Loren Eiseley on the relationship between nature and human nature and Terry Tempest Williams — a modern-day spiritual heir of Muir’s — on the wilderness as an antidote to the war within ourselves, then revisit Muir’s British contemporary Richard Jefferies on how nature’s beauty dissolves the boundary between us and the world.

donating=lovingEvery week for more than 13 years, I have been pouring tremendous time, thought, love, and resources into Brain Pickings, which remains free and is made possible by patronage. If you find any joy and solace in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation. And if you already donate, from the bottom of my heart: THANK YOU. (If you've had a change of heart or circumstance and wish to rescind your support, you can do so at this link.)

monthly donation

You can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch.

|

|

one-time donation

Or you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7

|

|

“How should we like it were stars to burn with a passion for us we could not return?” asked W.H. Auden (February 21, 1907–September 29, 1973) in “The More Loving One” — one of the greatest, most largehearted poems ever written. The son of a physicist, Auden wove science throughout much of his poetry — sometimes playfully, sometimes poignantly, always as a finely polished lens on the deepest moral and humanistic questions with which we live and for which we die. At the heart of his scientific poetics was the understanding that the eternal tension between knowledge and the unknown, enveloped in our ambivalent longings, is what makes us human.

Nowhere do these tessellated ideas and sensibilities come together more vibrantly than in his 1961 poem “After Reading a Child’s Guide to Modern Physics,” found in his indispensable Collected Poems (public library) and brought to life by musician Josh Groban at the third annual Universe in Verse.

Painting of W.H. Auden by astrophysicist Janna Levin

Following theoretical cosmologist and jazz saxophonist Stephon Alexander’s ardent case for the interbelonging of art and science, and reading to the background of an Auden portrait painted by astrophysicist, novelist, and poetry enchantress Janna Levin, Groban prefaced his reading of Auden with a remarkable personal story about his own great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather — a 17th-century German rebel astronomer and theologian, who allowed his scientific understanding of the cosmos to expand his spiritual life rather than contracting it with fear and dogma as the era’s church did — the same era in which Kepler’s revolutionary astronomy thrust his mother into a witchcraft trial.

Enjoy, and consider joining us in atoms for the fourth annual Universe in Verse, exploring the most fundamental question of existence: What is life?

AFTER READING A CHILD’S GUIDE TO MODERN PHYSICS AFTER READING A CHILD’S GUIDE TO MODERN PHYSICS

by W.H. Auden

If all a top physicist knows

About the Truth be true,

Then, for all the so-and-so’s,

Futility and grime,

Our common world contains,

We have a better time

Than the Greater Nebulae do,

Or the atoms in our brains.

Marriage is rarely bliss

But, surely it would be worse

As particles to pelt

At thousands of miles per sec

About a universe

Wherein a lover’s kiss

Would either not be felt

Or break the loved one’s neck.

Though the face at which I stare

While shaving it be cruel

For, year after year, it repels

An ageing suitor, it has,

Thank God, sufficient mass

To be altogether there,

Not an indeterminate gruel

Which is partly somewhere else.

Our eyes prefer to suppose

That a habitable place

Has a geocentric view,

That architects enclose

A quiet Euclidian space:

Exploded myths — but who

Could feel at home astraddle

An ever expanding saddle?

This passion of our kind

For the process of finding out

Is a fact one can hardly doubt,

But I would rejoice in it more

If I knew more clearly what

We wanted the knowledge for,

Felt certain still that the mind

Is free to know or not.

It has chosen once, it seems,

And whether our concern

For magnitude’s extremes

Really become a creature

Who comes in a median size,

Or politicizing Nature

Be altogether wise,

Is something we shall learn.

For other highlights from The Universe in Verse, savor Marie Howe reading her tribute to Stephen Hawking, Amanda Palmer reading Neil Gaiman’s tribute to Rachel Carson and his feminist correction of the history of science, Krista Tippett reading “Figures of Thought” by Howard Nemerov, Regina Spektor reading “Theories of Everything” by the astronomer and poet Rebecca Elson, and astrophysicist Janna Levin reading “A Brave and Startling Truth” by Maya Angelou, “Planetarium” by Adrienne Rich, and Whitman’s classic “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer.”

Years before Walter Lippmann explored stereotypes and the psychology of prejudice, rooted in the disquieting fact that “we do not first see, and then define, [but] define first and then see,” and decades before Hannah Arendt observed that “society has discovered discrimination as the great social weapon by which one may kill men without any bloodshed” before she drew on this insight to illuminate the relationship between loneliness and tyranny, the trailblazing anthropologist, sociologist, and folklorist Elsie Clews Parsons (November 27, 1875–December 19, 1941) took up these deep-rooted, interleaved questions in her prolific and prescient body of work.

Elsie Clews Parsons

A graduate of Barnard College, Parsons used her family wealth to fund the anthropology department at Columbia University during its wartime downturn and helped found The New School — New York’s iconic haven of intellectual freedom and progressive thinking. Greatly influenced by Margaret Fuller, Parsons not only advocated for but modeled women’s equal intellectual participation in culture, seeing difference not as a point of weakness but as a fulcrum of strength. In an era when social science was still emerging from the primordial waters of metaphysics onto the firm ground of methodology and was often tainted with the pseudosciences that gave rise to eugenics, in an era when very few women were accredited field researchers and published scholars, Parsons researched, wrote, and published more than a dozen deeply insightful works challenging many of the era’s damaging givens. Making Native American tribes the focus of her research, she saw native societies not as “primitive” cultures that had to be leveled with “civilization,” as the normative view of the era dictated, but as alternative models of social organization and cultural practices, valid in their own right and in many ways superior to those of her own society — cultures that had a great deal to teach, rather than be taught, about how to live.

Art by Beatrice Alemagna from A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader.

Parsons was drawn to this inquiry into alternative cultural models by her early and growing skepticism about her own culture’s problematic tendencies and the trajectory on which they were setting society. She became a radical voice of dissent, writing critically, with tremendous psychosocial insight and foresight, about the early signs of what would fester into some of the most troubling, oppressive, and dangerous realities of our own time. Of her many then-controversial works, the one that now stands as nothing short of prophetic is her 1916 book Social Rule: A Study of the Will to Power (public library) — an unheard admonition bellowing in the gun barrel of time, presaging the exploitation of the psychological vulnerabilities of the human animal that gave rise to the various totalitarian regimes that came to plague the globe in the century since, spurred the most concentrated genocide in the history of our species, and the continues to foment the maladies of racism, sexism, and nationalism still fraying the fabric of our shared humanity.

Art by Lia Halloran for The Universe in Verse. Available as a print.

Parsons begins with the elemental question of why we are so impelled to divide the world into categories and classes, and why we derive such pleasure from ranking our own above others, despite the enormous collective cost of these divisions:

In any study of the relations between personality and social classification the queries arise why the social categories are alike so compulsive to the conservative-minded and so precious, why they are given such unfailing loyalty, why such unquestioning devotion? To offset the miseries they allow of or further, the tragedies they prepare, what satisfaction do they offer? Do they serve only as measures against change, as safeguards to habit, — this raising barriers between those most apt to upset one another’s ways, the inevitably unlike, the unlike in sex, in age, in economic or cultural class? In any study of the relations between personality and social classification the queries arise why the social categories are alike so compulsive to the conservative-minded and so precious, why they are given such unfailing loyalty, why such unquestioning devotion? To offset the miseries they allow of or further, the tragedies they prepare, what satisfaction do they offer? Do they serve only as measures against change, as safeguards to habit, — this raising barriers between those most apt to upset one another’s ways, the inevitably unlike, the unlike in sex, in age, in economic or cultural class?

Well before Lippmann observed that “the systems of stereotypes may be the core of our personal tradition, the defenses of our position in society,” Parsons locates the answer to the paradox in precisely this self-securing social function of labels:

The social categories are no doubt a safeguard against the innovations personality untrammelled would be up to, and this protection is by no means a trifling social function;… they are an unparalleled means of gratifying the will to power as it expresses itself in social relations. The social categories are no doubt a safeguard against the innovations personality untrammelled would be up to, and this protection is by no means a trifling social function;… they are an unparalleled means of gratifying the will to power as it expresses itself in social relations.

[…]

The preeminent function of social classification appears therefore to be social rule… Classification is nine-tenths of subjection. Indeed to rule over another successfully you have only to see to it that he keeps his place — his place as a male, her place as a female, his or her place as a junior, as a subject or servant or social “inferior” of any kind, as an outcast or exile, a ghost or a god.

Art by Olivier Tallec from Louis I, King of the Sheep

Classification, Parsons observes, is not just what we do with others but what we do with ourselves in our struggle for belonging and self-inclusion — a struggle that sometimes metastasizes into a tendency toward punitive exclusion directed at those we place outside the boundaries of our self-elected classifications. In a sentiment of chilling relevance to a common malfunction of twenty-first-century identity politics — a necessary healing of painful historical exclusions in many ways, but also one, like all compensatory advancements, in danger of over-compensating by veering into an unhealing direction of further divisiveness — Parsons adds:

Self-control is a means to controlling other people. So is self-classification. The feeling of having our class back of us gives us self-assurance… we enhance our sense of power. Similarly, by declassifying or demoting others or by suspending their regular classification, so to speak, we get a pleasurable sense of our own power. Self-control is a means to controlling other people. So is self-classification. The feeling of having our class back of us gives us self-assurance… we enhance our sense of power. Similarly, by declassifying or demoting others or by suspending their regular classification, so to speak, we get a pleasurable sense of our own power.

With the eye to the history of civilizations, Parsons argues that “the bulk of our surplus energy, energy beyond that applied to sustaining life,” is exerted on subjugating others. Having long advocated for women’s equal inclusion in the intellectual, creative, and political spheres of society, she observes that even the classification feminist has been hijacked and contorted to work in a direction opposite to its intended purpose. Three years before women finally won the right to vote, and half a century after Walt Whitman insisted that “the sole avenue and means of a reconstructed sociology depended, primarily, on a new birth, elevation, expansion, invigoration of woman,” Parsons writes:

Even the woman movement we have called feminism has not succeeded by and large in giving women any control over men. It has only changed the distribution of women along the two stated lines of control by men, removing vast numbers of women from the class supported by men to the class working for them. Even the woman movement we have called feminism has not succeeded by and large in giving women any control over men. It has only changed the distribution of women along the two stated lines of control by men, removing vast numbers of women from the class supported by men to the class working for them.

[…]

The main objective of feminism in fact may be defeminisation, the declassification of women as women, the recognition of women as human beings or personalities. It is not hard to see why the classification of women according to sex has ever been so thorough and so rigid. As long as they are thought of in terms of sex and that sex the weaker or the submissive, they are subject by hypothesis to control… The more thoroughly a woman is classified the more easily is she controlled.

Art by Margaret C. Cook from a rare 1913 edition of Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

Economic caste distinctions, Parsons argues, operate along similar lines of social function. Decades before the golden age of consumerism opened its post-industrial jaws into gaping income inequality and swallowed the century, she writes:

Through consumption a still greater measure of difference is achieved. This achievement is particularly characteristic of course in the class that can best afford to elaborate its consumption, the capitalist class, but within the labour class too different standards of living, i. e. of consuming make for caste demarcations. Through consumption a still greater measure of difference is achieved. This achievement is particularly characteristic of course in the class that can best afford to elaborate its consumption, the capitalist class, but within the labour class too different standards of living, i. e. of consuming make for caste demarcations.

[…]

Conspicuous consumption, conspicuous waste is in all classes a manifestation of the will to power.

In another passage of extraordinary prescience, penned in the midst of one World War, decades ahead the unfathomed next, and a century before the xenophobic border catastrophes of our own time, Parsons considers nationalistic tendencies and the social domination of immigrants as particularly perilous expressions of this destructive will to power:

Naturalisation, as it is called in political terms, or, more comprehensively, assimilation is a complex process of classification which has of course more than one end… Making citizens is an outlet for the energy of many groups of the native born. When the outlet is denied them, when foreigners are considered too disparate for assimilation to become possible or when immigrants have resisted assimilation en masse by living in segregated communities, the native born are gravely concerned. They feel thwarted and they look for relief. Restriction of immigration is one of their favourite self-relief measures. Naturalisation, as it is called in political terms, or, more comprehensively, assimilation is a complex process of classification which has of course more than one end… Making citizens is an outlet for the energy of many groups of the native born. When the outlet is denied them, when foreigners are considered too disparate for assimilation to become possible or when immigrants have resisted assimilation en masse by living in segregated communities, the native born are gravely concerned. They feel thwarted and they look for relief. Restriction of immigration is one of their favourite self-relief measures.

Art by Yara Kono from Three Balls of Wool (Can Change the World) by Henriqueta Cristina — a poignant children’s book about immigration, nonconformity, and the courage to remake society’s givens

With a condemnatory eye toward a harsh immigration bill that had just been proposed, aiming to bar Hindus from entering the United States and to require an English literacy test from other immigrants, Parsons observes that such efforts to legalize discrimination are not just a momentary flinch from the terrors of a war-torn world but emblematic of a deeper, darker human folly — an observation that the following century, with its Japanese internment camps and Mexican border wall, would prove grimly astute:

This campaign against hyphenated Americans is an outcome of a particular state of panic, to be sure, but it must also be viewed as a consistent, if acute, part of the ordinary American attitude towards the immigrant. Or, to speak more justly, of the articulate Anglo-Saxon American’s attitude. This campaign against hyphenated Americans is an outcome of a particular state of panic, to be sure, but it must also be viewed as a consistent, if acute, part of the ordinary American attitude towards the immigrant. Or, to speak more justly, of the articulate Anglo-Saxon American’s attitude.

Far ahead of her time, Parsons argued for the respect and inclusion not only of the various races and the two sexes, but also — long before homosexuality was declassified as a mental disorder, the term LGBTQ coined, and the trans identity proudly claimed — for the rights of gender-nonconforming persons: “men-women or women-men, the unsexed.” She widened the circle of empathy and creaturely dignity to non-human animals, inveighing against cruelty and slaughter, and correctly terming the captivity of wild animals in zoos, circuses, and royal courts a form of “enslavement.”

Finally, turning to the essential humanistic lens that must govern all science — for she had seen science warped and politicized in fueling the racist ideologies that set her world ablaze with war, hatred, and exclusion — Parsons ends the book with an admonition we are yet to heed and a vision we are yet to realize — a vision for a world where science becomes not a tool of subjugation and extractionism but an emissary of the wonder of nature and human nature; a world in which diversity becomes not a point of divisiveness but a crowning glory of our interconnected fates:

Unless our culture does develop along certain lines, principally along the line of a greater tolerance for the individual variation, a greater respect for personality, scientific applications to society may indeed prove unimaginable tyranny. Aside from this possible turn of culture, however, there is another social relief in sight. Applied science will be concentrated more and more upon nature. This diversion of energy from controlling the animate or the moral to controlling the inanimate or the non-moral is in fact in process; it is already one of the most characteristic features of modern life. Thanks to the mechanical inventions it resulted in, it has led to innumerable new fields of work and play — for children, for women, and for other subject classes. It is transforming child-bearing and the education of children. It has meant public hygiene. Some day it may mean social art. It has transformed belief in the mystical efficacy of staying home into concern over home conditions. It has meant improving neighbourhoods (rather than regulating neighbours). It has directed attention from the ethics of proprietorship to the ethics of use. It has meant the preservation of natural resources, substituting here as elsewhere the idea of collective ownership for the theory of natural rights and private property. It has meant a world-wide system of communication and transportation. Some day it will mean industrial democracy. Some day it will mean the disappearance of nationalisation as it is now understood and the disappearance of national wars. Through lessening interest not only in political boundaries but in all social boundaries it will force a condition of greater social tolerance in general, precluding the individual from masking an attitude of arrogance or tyranny under a social classification. In it, in the concentration of our energy upon bettering nature rather than upon bettering man, or, shall we say, in bettering human beings through bettering the conditions they live under, in such outlets for effort and ambition I find the opportunity par excellence for a greater measure of social freedom. Unless our culture does develop along certain lines, principally along the line of a greater tolerance for the individual variation, a greater respect for personality, scientific applications to society may indeed prove unimaginable tyranny. Aside from this possible turn of culture, however, there is another social relief in sight. Applied science will be concentrated more and more upon nature. This diversion of energy from controlling the animate or the moral to controlling the inanimate or the non-moral is in fact in process; it is already one of the most characteristic features of modern life. Thanks to the mechanical inventions it resulted in, it has led to innumerable new fields of work and play — for children, for women, and for other subject classes. It is transforming child-bearing and the education of children. It has meant public hygiene. Some day it may mean social art. It has transformed belief in the mystical efficacy of staying home into concern over home conditions. It has meant improving neighbourhoods (rather than regulating neighbours). It has directed attention from the ethics of proprietorship to the ethics of use. It has meant the preservation of natural resources, substituting here as elsewhere the idea of collective ownership for the theory of natural rights and private property. It has meant a world-wide system of communication and transportation. Some day it will mean industrial democracy. Some day it will mean the disappearance of nationalisation as it is now understood and the disappearance of national wars. Through lessening interest not only in political boundaries but in all social boundaries it will force a condition of greater social tolerance in general, precluding the individual from masking an attitude of arrogance or tyranny under a social classification. In it, in the concentration of our energy upon bettering nature rather than upon bettering man, or, shall we say, in bettering human beings through bettering the conditions they live under, in such outlets for effort and ambition I find the opportunity par excellence for a greater measure of social freedom.

Complement with the great humanistic philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm, a cultural descendent of Parsons, on the sane society and what will save us from ourselves, then revisit James Baldwin’s classic “Stranger in the Village,” exploring these complex issues along the tightrope between conviction and nuance the way only Baldwin can.

donating=lovingEvery week for more than 13 years, I have been pouring tremendous time, thought, love, and resources into Brain Pickings, which remains free and is made possible by patronage. If you find any joy and solace in my labor of love, please consider supporting it with a donation. And if you already donate, from the bottom of my heart: THANK YOU. (If you've had a change of heart or circumstance and wish to rescind your support, you can do so at this link.)

monthly donation

You can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch.

|

|

one-time donation

Or you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7

|

|

|

|

| | |