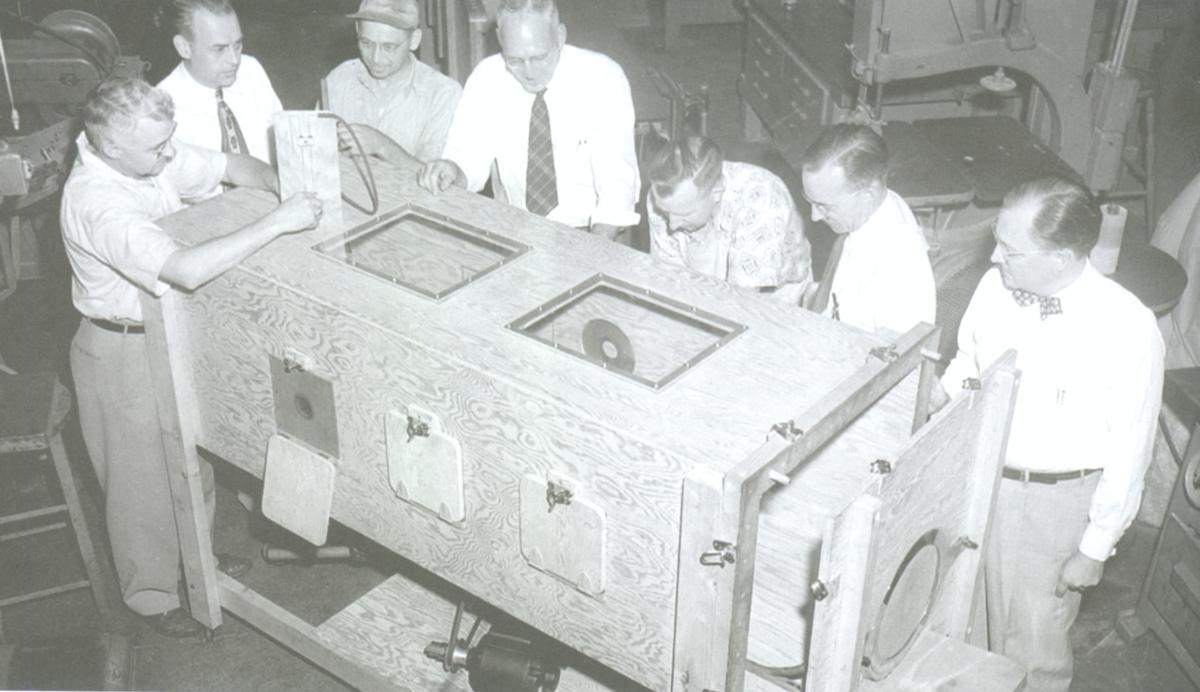

A Piece From Our Past: 'Wooden' lung ingenious contraption for polio epidemic | Mclean County Museum Of History | The Pantagraph.

[Source article may not be viewable in EU except via a suitable VPN]

Ingenuity helped Bloomingtonians solve problems during the shortage of iron lungs in 1949.

COURTESY, MCLEAN COUNTY MUSEUM OF HISTORY

In the summer of 1949, at a time when Central Illinois communities were hit particularly hard by the deadly disease polio, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Eureka Williams Corp. decided to fight back.

Officials with St. Joseph (then located on Bloomington’s west side) feared their two iron lungs might not be enough at any one time, a shortage that might endanger the life of someone who needed but could not get one. As a result, engineers and machinists from Bloomington manufacturer Eureka Williams volunteered to design and build one from scratch using everyday household materials.

As a fully functioning negative pressure ventilator, this “wooden” lung (so-called because its frame was built of plywood) did the same job as the polished, commercially manufactured “iron” ones. It was an ingenious mechanical feat that drew national attention.

Poliomyelitis (polio’s scientific name, though it’s often known as infantile paralysis) is a virus that spreads person to person. The disease, for which there is no known cure, can lead to atrophied muscles and paralyzed, misshapen limbs, and at its most dangerous, death from suffocation. Many who grew up during the polio epidemics after World War II recall all too well friends, neighbors or family members subjected to confinement in iron lungs, leg braces, corrective footwear and painful physical therapy.

Polio patients sometimes lost the ability to control the muscles involved in breathing. An iron lung was a cylindrical, bed-like machine in which patients were treated with rhythmic fluctuations in air pressure, forcing oxygen in — and carbon dioxide out — of the lungs. An iron lung was usually needed for several days or weeks until the virus ran its course, though a small number of patients ended up spending the greater part of their lives tied to such machines.

On Friday, August 5, 1949, members of the Eureka Williams engineering staff and a handful of volunteers were at the Bell Street plant to start the ambitious project. Fifteen men worked all day Saturday and through to midnight Sunday to finish the job.

Over the same weekend, polio killed two at St. Joseph’s: John Lynch, age 2, of Gibson City; and Mary Guyon, age 11, of Streator. These deaths and the hospital’s growing caseload likely weighed heavily on the minds of those working at Eureka Williams.

The six-foot-long wooden lung was built from materials “you’d find in any hardware store or lumber shop in any one-horse town,” noted Ralph C. Osborn, Eureka Williams vice president of engineering. “Our idea was to make a lung that any carpenter can build anyplace it’s needed.” The “Bloomington lung” was put together using, among other items, household electrical switches; a washing machine motor and gear box; an inner tube from a tractor tire; a wash tub; an alarm clock; and the aforementioned plywood.

On August 10, the machine was put to an unexpected life-and-death test. That night, 8-year-old Rudy Landherr of the Whiteside County community of Morrison arrived at St. Joseph’s to find both iron lungs occupied. With paint still drying on the plywood, hospital staff realized they had no other choice than to use the wooden lung. Landherr remained inside the cobbled-together machine through the night, unable to breathe without it. The next morning he was moved to an iron lung when one became available.

The Bloomington lung saved the boy’s life, announced Sister M. Celine Friske, St. Joseph’s chief administrator. “I didn’t have to breathe,” Landherr told a Pantagraph reporter several weeks later. “It breathed for me.” He ended up living to the age of 65, passing away in the summer of 2006 in his hometown of Morrison.

Back in 1949, news of the wooden lung, which eventually earned the American Medical Association’s seal of approval, spread fast across the nation. Both Associated Press and United Press International ran the story on their national wire, and local officials found themselves inundated with requests for blueprints. Eureka Williams eventually published a 12-page how-to booklet, and by late 1951 had sent copies to more than 1,000 groups around the country. Popular Mechanics magazine even featured Bloomington’s “emergency wooden respirator” in its January 1952 issue.

Jonas Salk was the first to cross the finish line of the “Great Race,” developing a polio vaccine in 1952 (though its announcement wasn’t made until 1955). Albert Sabin followed shortly thereafter with an oral vaccine, famously administered with sugar cubes. Since then, polio has been eradicated in the United States and the rest of the Americas, but is still endemic in several countries, including Afghanistan.

+++

[The Pantagraph] Editor's note: This story originally was published Nov. 21, 2009. Pieces From Our Past is a weekly column produced by the McLean County Museum of History.

Original Source Article »

+++

When Polio Triggered Fear and Panic Among Parents in the 1950s | History.

[MAR 27, 2020]

Since little was understood about the virus that left some paralyzed and others dead, fear filled the vacuum.

Volker Janssen writes:

In the 1950s, the polio virus terrified American families. Parents tried “social distancing”—ineffectively and out of fear. Polio was not part the life they had signed up for. In the otherwise comfortable World War II era, the spread of polio showed that middle-class families could not build worlds entirely in their control.

For the Texas town of San Angelo on the Concho River, halfway between Lubbock and San Antonio, the spring of 1949 brought disease, uncertainty and most of all, fear. A series of deaths and a surge of patients unable to breathe prompted the airlifting of medical equipment with C-47 military transporters.

Towns Practice Extreme Social Distancing.

Children in San Angelo residential areas watch Texas Health employees spray DDT over vacant lots in the city to combat a recent increase in the number of polio cases. All theaters, swimming pools, churches, schools and public meeting places were closed.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Fearful of the spread of the contagious virus, the city closed pools, swimming holes, movie theaters, schools and churches, forcing priests to reach out to their congregations on local radio. Some motorists who had to stop for gas in San Angelo would not fill up their deflated tires, afraid they’d bring home air containing the infectious virus. And one of the town’s best physicians diagnosed his patients based on his “clinical impression” rather than taking the chance of getting infected during the administration of the proper diagnostic test, writes Gareth Williams, Paralyzed with Fear: The Story of Polio. The scene repeated itself across the nation, especially on the Eastern seaboard and Midwest.

The virus was poliomyelitis, a highly contagious disease with symptoms including common flu-like symptoms such as sore throat, fever, tiredness, headache, a stiff neck and stomach ache. For a few though, polio affected the brain and spinal cord, which could lead meningitis and, for one out of 200, paralysis. For two to 10 of those suffering paralysis, the end result was death.

Transmitted primarily via feces but also through airborne droplets from person to person, polio took six to 20 days to incubate and remained contagious for up to two weeks after. The disease had first emerged in the United Sates in 1894, but the first large epidemic happened in 1916 when public health experts recorded 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths—roughly a third in New York City alone.

After rabies and smallpox, polio was only the third viral disease scientists had discovered at the time, writes David Oshinksi in Polio: An American Story. But a lot remained unknown. Some blamed Italian immigrants, others pointed to car exhausts, a few believed cats were to blame. But its long incubation period, among other things, made it difficult even for experts to determine how the virus transferred.

'Fly Theory' Falsely Associated Polio With Insects.

A fly trap was used at the house of a child with polio to collect specimen flies to be sent to Yale University for polio research experiments.

Alfred Eisenstaet/Getty Images

The prevalence of polio in late spring and summer popularized the “fly theory,” explains Vincent Cirillo in the American Entomologist. Most middle-class Americans tended to associate disease with flies, dirt and poverty. And the seasonal surge of the disease in summer and apparent dormancy in winter matched the rise and fall of the mosquito population.

After World War II, Americans doused their neighborhoods, homes and children with the highly toxic pesticide DDT in the hope of banishing polio, Elena Conis reports in the journal Environmental History. Yet, the number of cases grew larger each season. There were 25,000 cases in 1946—as many as in 1916, writes Oshinski—and the number grew almost every year up to its peak of 52,000 in 1952.

There were signs of hope. The 1930s had seen significant improvements in the iron lung, a negative pressure chamber that could assist the breathing process for severely paralyzed patients. The March of Dimes organization campaigned aggressively to fund the development of a vaccine. And the comparable odds of contracting the disease remained small, the odds of long-term consequences minute, to say nothing of death.

Polio Hysteria Finally Subsides With Vaccine.

American scientist and physician Jonas Salk developed the polio vaccine.

PhotoQuest/Getty Images

The Journal of Pediatrics, parenting guru Benjamin Spock, every expert and most editorial boards warned against irrational “polio hysteria.” And yet, Oshinski tells us, headlines and images of polio victims were familiar features on the front pages in the summer months. American parents were petrified. A 1952 survey found that Americans feared only nuclear annihilation more than polio.

The random pattern the disease struck made parents feel helpless, as was the lack of a cure. As middle-class parents saw it, something like this was not supposed to happen. Infectious disease had been the leading cause of death in 1900, it was no longer in 1950. They had survived the Great Depression, fought and won World War II, and returned safely from a dangerous world. Oshinski shares this recollection of a journalist from that time: “Into this buoyant postwar era came a fearsome disease to haunt their lives and to help spoil for those young parents the idealized notion of what family life would be. Polio was a crack in the fantasy.”

By 1955 epidemiological evidence had clearly established that mosquitoes and flies played no important role in polio epidemics and Jonas Salk had announced he’d developed a polio vaccine, making the issue moot. Today, polio has largely been eliminated in the United States. Salk was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977.

+++

Volker Janssen is a professor of California State University Fullerton who specializes in the social, economic, and institutional history of California.

Original Source Article »

+++

Lessons learned from Indonesia's polio outbreak to defeat coronavirus | Antara English News.

[28th March 2020]

Polio vaccine in the immunization program in Indonesia. (ANTARA/Herry Murdy Hermawan)

With the number of new cases continuing to swell, the novel corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been declared as an extraordinary occurrence by Indonesia.

As of Saturday afternoon, the number of positive cases had crossed the one thousand-mark to touch 1,155. And yet, many seem to believe the peak is yet to come. The country reported its first cases earlier in the month, on March 2.

“We believe that we are a great nation, a fighter of a nation. God willing (Insya Allah), we will face this difficult global challenge,” said President Joko Widodo on Tuesday, March 24, as the country battled a rising number of cases in a pandemic that has caught the world off guard.

The President’s faith in Indonesia’s ability to overcome such an aggressive viral infection is not without reason. The country has overcome its fair share of battles in the past with diseases that have threatened the health and wellness of its citizens.

Anyone born in Indonesia in the 1990s would most likely have a memory of getting vaccinated against poliomyelitis, or polio, at a young age. They may remember a shot in their arm or drops of the sweet-tasting immunization liquid in the mouth, which were meant to inoculate them against a disease that could drastically change the course of their lives.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes poliomyelitis as “a highly infectious viral disease, which mainly affects young children.”

The virus is transmitted person-to-person, mainly through the faecal-oral route or, less frequently, by a common vehicle such as contaminated water or food, and multiplies in the intestine, from where it can invade the nervous system to cause paralysis, according to the WHO.

The WHO declared Indonesia polio-free in 2014. The Ministry of Health stated that the last polio virus to originate in Indonesia — Type-1 in east Java and Type-3 in North Sumatra —was isolated in 1995.

The country witnessed another Type-1 polio outbreak between 2005 and 2006, and it was declared an extraordinary occurrence. The Health Ministry later revealed the outbreak had been caused by an imported case from the Middle East.

According to the government’s Infeksi Emerging (Emerging Infections) page, after three National Immunization Weeks for Polio were held in 1995,1996, and 1997, wild polio viruses indigenous to Indonesia were no longer detected in 1996.

However, on March 3, 2005, a polio case emerged in Sukabumi, West Java, which then developed into an extraordinary occurrence, as the virus spread to 10 provinces and 47 districts and cities across the country, with the total number of cases reaching 305.

There were also 46 cases of vaccine-derived polio virus, which emerged after a substantial number of children did not get vaccinated. Forty-five of these cases were reported from the island of Madura, while one was registered in Probolinggo, East Java.

The Indonesian Government was able to contain the outbreak through an Outbreak Response Immunization (ORI), which involved two rounds of door-to-door immunizations (mop-ups) in high risk areas, five National Immunization Weeks, and two Sub-National Immunization Weeks.

The Indonesian Government had to resort to vaccination drives in the absence of medications for polio. Those who contract the virus can only be administered drugs to manage symptoms, such as fever and muscle discomfort. For this reason, measures against polio remain preventive in nature.

Immunization is still helping Indonesia keep polio at bay. Although the country has been declared polio-free, it aims to conduct a National Immunization Week every year for polio prevention. The most recent one, however, was conducted in 2016.

Aside from vaccines, hand-washing is an effective preventive measure against the spread of polio as it eliminates the possibility of oral infections. Consumption of cooked food, which is nutritious, and clean water can help keep infections at bay by boosting the immune system. Taking vitamins and staying hydrated are also important to avoid polio.

Considering the fact that polio can spread through contact with feces of patients, proper sanitation, especially in public toilets, is of vital importance. Especially those used by toddlers and young children.

Like in the case of poliomyelitis, precautionary measures are perhaps our best option for warding off COVID-19 infections, as there are currently no readily available medications for treating the disease.

Indonesia has been able to overcome a number of epidemics in the past, and Indonesians should remain optimistic in the fight against the spread of the coronavirus.

Original Source Article »

+++

India: Taking a page from the Covid manual to tackle TB and other infectious diseases | The Hindu Business Line.

[March 28, 2020] Dalbir Singh writes:

Covid-19 is currently the spectre at the feast. But the pandemic must not be seen in isolation.

Rarely has the world been so united as in the past few weeks since the outbreak of Covid-19, which has spread across the globe like wildfire. Since Covid-19 is uncharted territory, the endeavour to tackle this deadly virus entailed a clear vision, an effective strategy, collective action and deeper coordination between diverse agencies.

While the world looks towards the scientific community for a cure and vaccine for Covid-19, we still have an ancient disease like tuberculosis (TB) which claims more lives than any other infectious disease in history and it has struck back with vengeance, killing 4,000 and infecting 30,000 people every day across the globe. In India, 1,600 people perish every day because of this mycobacterium.

Maintain vigil, debunk myths.

Although Covid-19 is a viral infection and TB is bacterial, they are transmitted through the same mediums. Preventive measures being advertised for Covid-19 are the same as required in our response to TB. By maintaining proper hygiene and cough etiquette, not only can we help in curbing the spread of Covid-19 but also the spread of TB. Against the backdrop of World TB Day (March 24), I believe that we need not wait for a pandemic to prioritise our attention and vigilance against public health threats, especially infectious diseases. Rather, we must maintain a consistent drumbeat to keep ourselves abreast and share accurate information around why and how these issues can be tackled. Be it Covid-19, TB or even HIV, there is a dire need to increase awareness to ensure informed actions and evolve appropriate strategies and policies to overcome these challenges.

A recent note by the World Health Organization emphasises this point: “Health services, including national programmes to combat TB, need to be actively engaged in ensuring an effective and rapid response to Covid-19 while ensuring that TB services are maintained".

While TB is preventable and curable, misconceptions about the disease have led to discrimination and stigma — complicating its treatment even further. Fearing societal reactions, people with symptoms of TB avoid seeking medical attention.

By actively debunking myths about Covid-19, the Indian government has shown that it has the capacity to address these issues boldly and decisively. The same level of response and concerted efforts need to be drawn into TB elimination efforts as well. Not only would this raise the profile of the disease in India but also address the grave societal issue of stigma, social discrimination and ostracisation of TB patients within the community and at the workplace.

Pivotal role for Influencers.

Public influencers can play a pivotal role — celebrities like Amitabh Bachchan have campaigned for critical public health issues like Polio and TB. Now others — elected representatives, actors, musicians, sportspersons — should help generate mass awareness about TB, its treatment and preventive measures. The collective action of government, public influencers, healthcare professionals, civil society and local communities will go a long way in raising the visibility of the disease, tackling myths and misconceptions and in helping preventive measures at the grass-root level.

Covid-19 is currently the spectre at the feast. But it must not be seen in isolation. We must share experiences and knowledge on proven interventions, incorporate innovative solutions, build partnerships and coalitions, reduce morbidity and tackle other infectious diseases taking a heavy toll on our population with the same commitment and mission approach.

The writer is President, the Global Coalition Against TB.

+++