Jul 24, 2019 10:32 am

The French brig sloop ‘Curieux’ was fitted out at Martinique in order to attack British interests, as she was a threat to British West Indian commerce, the British Commodore Hood gave orders for her capture. Under the command of Lieutenant Robert Carthew Reynolds four boats with 60 seamen and 12 marines set out on a moonlit night from the British ship ‘Centaur’. This meant a 20-mile row to reach the ‘Curieux’ lying under the protection of the guns of Fort Edward.  When Reynolds’s barge came in under the stern of the ‘Curieux’ he found that, providentially, a rope ladder hung down the side. He scaled it and cut a hole in the anti-boarding nets to enable his men to pour on board. Before she was taken the French lost nearly 40 killed and wounded. The British had nine wounded including Reynolds. The British sent Curieux under a flag of truce to Fort Royal to hand the wounded over to their countrymen. The Royal Navy took her into service as HMS Curieux, a brig-sloop. Reynolds commissioned her but he had been severely wounded in the action and though he lingered for a while, died in September Painting: The cutting out of the Curieux, Martinique, 4th February 1804, Mark Richard Myers, P.R.S.M.A. (San Mateo, California b.1945)

Read in browser »

Jul 24, 2019 10:05 am

On July 24, the allied fleet arrived outside Gibraltar. In all, Rooke commanded 16 English ships under Byng and six Dutch ships under Rear Admiral Paulus van der Dussen. The ships positioned themselves inside the harbor, carefully out of range of the bastion’s guns. Rooke directed matters from his flagship, Royal Katherine, at the entrance to the bay. Beginning with a brief covering barrage laid down by the guns of his fleet, Rooke launched an amphibious assault by 1,900 English and 400 Dutch marines.  Their initial objectives were the main shore defenses, the Old and New Moles, and the fortified Teurto Tower.From 500 yards out to sea, the attackers (soldiers with muskets and swords and sailors armed with cutlasses, boarding pikes, and pistols) clambered down from their transport vessels onto a variety of launches, ships boats, skiffs, and barges to make their approach to the objectives. Small cannons were also made ready to be sent ashore if needed. It was the first time that Rooke’s floating armada had conducted an amphibious assault and the largest one ever attempted by an English force up to that time. Within an hour after setting off from the mother ships, the invaders landed on the sandy isthmus at the northern end of the Gibraltar peninsula. After forming into columns and advancing a short distance to attack the New Mole Fort, the English were struck by a devastating setback. Either a mine was set off by the defenders or else a powder magazine accidentally detonated—no one could determine which—and the assaulting force was wracked by a powerful explosion that killed or wounded 100 attackers.  Immediately after the deafening blast occurred, the surviving members of the landing party froze in their tracks, looking in shocked amazement at the loss of life and the wretched condition of the ground caused by the unexpected event. Unsure whether it was safe to carry on the attack, some of the men fell to the earth seeking shelter, while others ran back toward the landing boats. But most of the attackers simply remained stationary and silent. Those officers who remained alive and unhurt, along with hard-bitten sergeants and corporals, rapidly regained their senses and hurried to calm the men and put them back into some sort of formation. As the English marines regained their composure and prepared to continue the advance, reinforcements came ashore. Soon the reorganized English-Dutch force headed for the fort. Encircling the installation and discharging their firearms, the allies stormed and took the place. Two columns of men were dispatched to surround the town. Meanwhile, sailors from the fleet secured the surrounding heights. They had been selected for the task because of the agility and speed with which they normally performed their shipboard duties. Soon the Spanish defenders began displaying white flags signaling their desire to surrender.  In 1827, the battle honours of the Royal Marines being so numerous (109 at this point), King George IV directed that the “Great Globe” itself should form their cap badge and that the single battle honour “Gibraltar” be selected as representative of all the others worn by the Corps. “Gibraltar” remains today the sole battle honour shown on the Regimental Colours of the Royal Marines.

Read in browser »

Jul 16, 2019 05:22 am

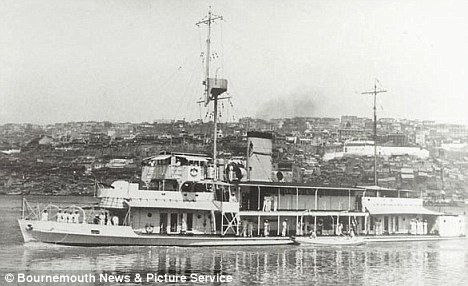

The British serviceman who first fired on Japanese forces during World War Two. Jim Mariner was on board the gunboat HMS Peterel when he secured his place in history at about 4am on December 7, 1941. I walked along and up the ladder on to the gun deck, which was now all action stations. 'Then red lights went into the sky and all hell broke loose. We thought it was going to be a mass invasion but it wasn't. 'They wanted to blow us to pieces. I just opened fire with my gun.' He recalled how he and several colleagues tried to escape in a small motor boat tied alongside, but ultimately swam for safety. He said: 'We always had trouble starting the engine on this blasted thing. 'One of our fellows got down there trying to start the engine and he said: "I'll get this thing going if it's the last thing I do". 'And it was, he took a direct shot. He said: "I've had it now" as he died. He was a very brave man. 'It was dreadful. The noise was shocking. They were at point blank range and they blew us to smithereens. 'I never thought I would get out of it alive.' After swimming to a Panamanian ship which he thought was safe, he was taken prisoner by Japanese troops that boarded her. The Japanese declared war on Britain the next day. HMS Petrel in Shanghai At the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 many ships and personnel from the Royal Navy's China Squadron were recalled to home waters, or sent to the Mediterranean. A number of river gunboats were considered of limited value and these were laid up locally.  One river gunboat, HMS Peterel, was retained in Shanghai to provide a token British military presence that it was hoped would dissuade the Japanese (who had already occupied most of the city) from moving against the International Settlement there. Her crew was reduced to 21 and 19 locally recruited Chinese; she was moored in the pool of Shanghai (off the French Concession). With her reduced complement, she was capable of steaming for only a limited period of time and her main armament had been disabled to lessen her value to the Japanese in the event of capture. Her captain (62-year-old Temporary Lieutenant Stephen Polkinghorn (RNR)) was under orders to scuttle the vessel should the Japanese attack. Sinking By December 1941 Shanghai (aside from the International Settlement and French Concession), had been occupied by Japan's land forces and there was a large buildup of Japanese naval forces in the area. At around 4:20am local time on 8 December 1941 news of the attack on Pearl Harbor, a few hours earlier, began filtering through to Shanghai. HMS Peterel was notified of the attack by Commander Kennedy from the British Consulate and the ship was called to battle stations. Soon after the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor reached Shanghai, Japanese marines boarded the US Navy river gunboat, USS Wake. She surrendered without a shot being fired (the only US Navy ship to surrender during World War II). The Japanese later commissioned her into their navy as the Tatara and subsequently gave her to its puppet Reorganized National Government of China based in Nanjing.  Although Japan had not declared war on Great Britain, Japanese marines also boarded the Peterel to demand her surrender. Polkinghorn attempted to stall for time, in order for the demolition fuses to be lit and the code books to be passed down a special chute in order to be burned in the boiler room. When his attempts failed, Polkinghorn told them to "Get off my bloody ship!" The Japanese disembarked and almost immediately the Japanese cruiser Izumo, the accompanying gunboat Toba and Japanese shore batteries in the French Concession opened fire at almost point-blank range. Despite being outnumbered and hopelessly outgunned, the Royal Navy crew of HMS Peterelreturned fire, using small arms and the deck-mounted Lewis machine guns (the breechblocks from her 3-inch guns having been removed and taken to the Royal Navy dockyard in Hong Kong). The Royal Navy crew inflicted several casualties on the Japanese before Peterel capsized and drifted from its mooring under heavy fire. The Japanese machine gunned both the surviving Royal Navy and locally recruited Chinese crewmen in the water. Of the British crew of 22, 18 were on board Peterel at the time of the attack. Six of them were killed by the Japanese; they have no known graves and it is unclear whether their bodies were recovered from the water. 12 Royal Navy crew survived: some sought refuge on a neutral Panamanian-registered merchant vessel, the SS Marizion. In violation of international law, the Japanese boarded the ship and took the survivors prisoner. The number of casualties suffered by the locally recruited non-combatant Chinese crew and the fate of any survivors at the hands of the Japanese is unknown (under a directive ratified on 5 August 1937 by Emperor Hirohito, the Japanese removed the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners by its military). The Royal Navy survivors from HMS Peterel (including Polkinghorn) were moved amongst the Hongchew, Kiang Wang and Woosung internment camps in China. Ongoing supplies received from the British Residents Association (Shanghai) and the International Red Cross were critical to the survival of those interned. On 9 May 1945 the inmates at Kiang Wang were moved to camps in Japan itself. Three of the crew of HMS Peterel were onshore during the Japanese attack; two were captured but the third (PO Telegraphist James Cuming) remained at large in Shanghai for the duration of the war, working for a Sino-American spy ring. The Lonely Battle, an account of Cuming's tale, was written by Desmond Wettern in 1960. Aftermath Polkinghorn survived his three years and nine months in captivity. He was awarded a gallantry medal, the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), for his actions in Shanghai. The citation (published in The London Gazette on 23 October 1945) reads: "For great courage, determination and tenacity in fighting his ship, HMS Peterel, when attacked by overwhelming Japanese forces at Shanghai on 8th December 1941". A small collection of photographs displayed at the Bund Historical Museum in Shanghai records the scene in the pool of Shanghai in the days both before and after 8 December 1941. Included in the collection are images of the badly damaged, capsized hulk of HMS Peterel.

Read in browser »

Jul 06, 2019 07:13 am

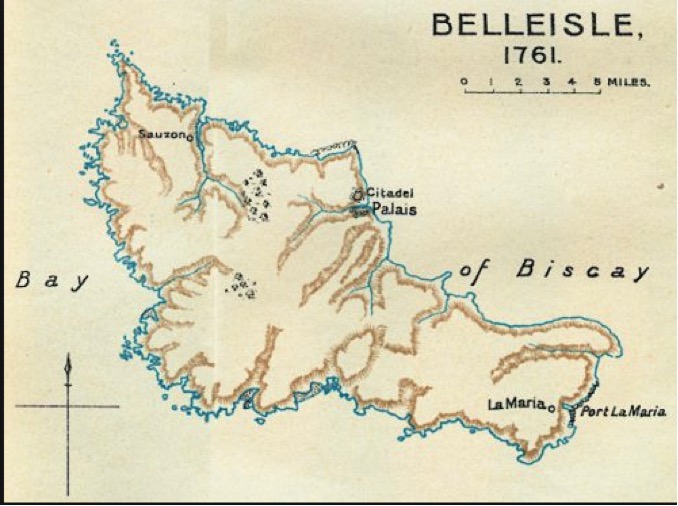

The Marines played a major role in the capture of this island, from the first amphibious landing, and through all subsequent fighting.  The Capture of Belle Île was a British amphibious expedition to capture the French island of Belle Île off the Brittany coast in 1761, during the Seven Years' War. After an initial British attack was repulsed, a second attempt under General Studholme Hodgson forced a beachhead. A second landing was made, and after a six-week siege the island's main citadel at Le Palais was stormed, consolidating British control of the island. Two battalions of Marines, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel John McKenzie, served with great distinction at the siege of Belleisle, and island off the north-west coast of France near St Nazaire in Quiberon Bay. With the 19th Regiment, these two units effected their first successful seabourne landing in the face of stiff opposition. They took part in all subsequent fighting on the island. The Marine battalions gained great fame at the final storming of the redoubts in June. Of their conduct on this occasion the Annual Register for 1761 said: "No action of greater spirit and gallantry has been performed during the whole war". The laurel wreath borne on the Colours and appointments of the RM is believed to have been adopted in honour of the distinguished service of the Corps during this operation.  The British occupied the island for two years before returning it in 1763 following the Treaty of Paris.

Read in browser »

Jul 04, 2019 07:45 am

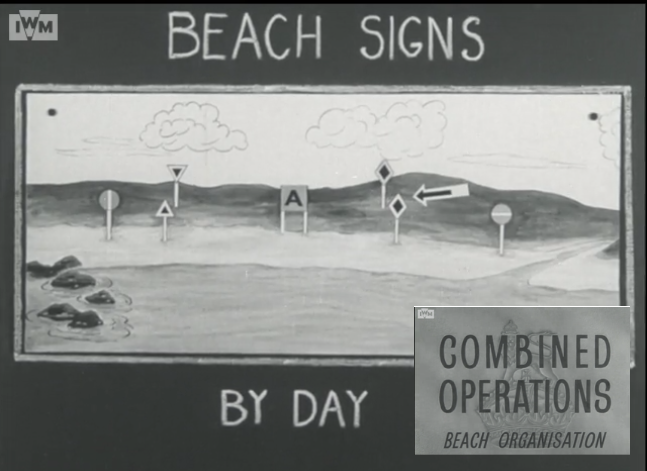

Lessons Learned (Operation Husky) The beach organisation was better than 'Torch' but there were still problems caused, mainly by human error. One example was the misuse of the miraculous DUKW, a 2.5 ton American amphibious lorry. Those carrying troops should have deposited them on or near to the landing beaches but chose to deliver their human cargo close to the front line. The congestion in the narrow Sicilian streets and roads was chaotic, at a time when the movement of supplies and weapons was a priority. One DUKW was loaded with 10 tons of ammunition, when the limit was a quarter of this. To the considerable consternation of the driver, his DUKW disappeared below the waves as he left the ramp!  Improved waterproofing of vehicles and recovery measures for stranded or broken down craft, reduced losses to as little as 1.5% on the British beaches. On the more exposed western beaches, losses were around 12%. The small harbour of Licata had a greater ship handling capacity than thought and this relieved pressure on supplies and communications, as well as reducing dependence on Syracuse and Augusta. Human errors of judgement in the management and control of men and materials, through the landing beaches, caused delays and loss of effectiveness. This unenviable and arduous job was that of Beachmaster. There was critical comment from senior staff about the selection criteria, recruitment and authority of the post holder. However, by the time of the Normandy landings, they had gained in respect and authority. One beachmaster is reputed to have ordered a general to "Get off my bloody beach!" "Beachmasters and assistant beachmasters should be men of personality, experience and adequate seniority, capable of exercising complete control in the dark." (McGrigor). "Naval Beachmasters should be preferably bad tempered and certainly dictatorial by nature." (Henriques). "The Brick (Beach) Commander must be King of the Brick (Beach) area" (Maund). "Some of the American Beachmasters are too junior and too polite to Generals." (General Wedemeyer of Eisenhower's staff). There were abuses in the deployment of men and materials. One divisional commander re-deployed men engaged on shifting supplies. Within 12 hours, they were on the front line. He later complained about delays in supplies reaching the front lines! Too many senior officers, who should have known better, regarded the Beach Groups as a "God-sent pool of everything." Later reports from different sources criticised this phase of the operation. Pilfering was rife. The Americans had a standard operating procedure (SOP) for the landing of men and materials. This required all the men and materials for the first battalion to go ashore, to be carried on one ship. However, there was no ship capable of carrying all the landing craft needed, so other landing craft were drafted in from nearby ships. This arrangement required a high degree of training and complete immunity from enemy interference. Potentially, as landing craft moved around in the dark, going from one vessel to another, some might get lost and others delayed. Henriques put his concerns to Patton, who seriously considered adopting the British technique but decided that it was too near the operational date to make last-minute changes. In the event, thorough rehearsals by the Americans and the lack of opposition from the enemy,enabled the system to work.  Under the British system, the troops, their equipment and the landing craft they needed to reach the beaches, were distributed amongst a number of ships so that each was self contained and able to independently disembark their cargoes in their own landing craft. Under these arrangements, there was no need to use landing craft from other ships, thus avoiding the inherent difficulties mentioned earlier. Truscott's landings, using the British method, were particularly successful. Principles for amphibious landings honed and developed over years of Combined Operations experience, were put into practice. Henriques attributed his success to; naval simplicity; speed coupled with a due allowance of time for the beach group to develop the beaches uninterrupted, surprise in that a substantial proportion of infantry were ordered to by pass resistance and effect, with utmost speed, a deep penetration into the high ground that commanded the prospective bridgehead and its approaches, the mobilisation and concentration of every possible means of fire support for the initial landings, the provision of specially equipped and specially trained assault troops to fight in the units in which they disembarked, the sacrifice of normal military organisation to this end, the retention of a very powerful floating reserve, adequate and carefully planned rehearsal with a due allowance of time for correction of faults, planning in minute detail which engendered sufficient confidence to confront unforeseen problems with flexibility. Henriques was also very impressed with US Navy crews. "Their coolness and discipline were quite outstanding and could never be forgotten by any of the soldiers taking part in the operation." Other lessons were learned from the Americans. Whereas the British basic beach group unit was an infantry battalion, the Americans had an Engineer Shore Unit with a high proportion of technically qualified men. Such skills were invaluable in quickly resolving unforeseen problems in the area of the beachhead. In addition, the Americans had an efficient and effective method of loading store ships, with groups of stores secured together for loading into DUKWs for easier dispatch to the shore.

Read in browser »

Jul 04, 2019 06:03 am

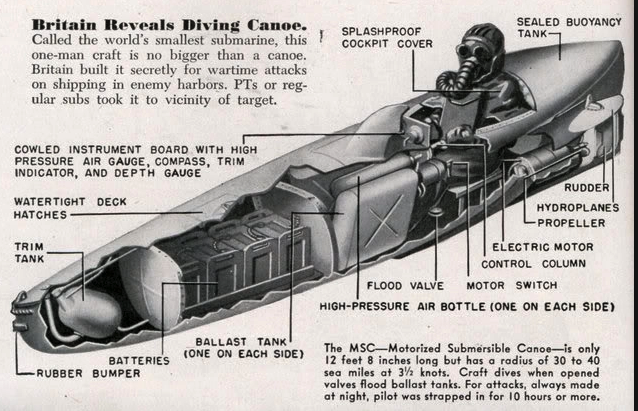

Operation Rimau was an attack on Japanese shipping in Singapore Harbour, carried out by an Allied commando unit Z Special Unit, during World War II using Australian built Hoehn military MKIII folboats. It was a follow-up to the successful Operation Jaywick which had taken place in September 1943, and was again led by Lieutenant Colonel Ivan Lyon of the Gordon Highlanders, an infantry regiment of the British Army. Ivan Lyon, now a lieutenant colonel, believing that the Japanese would not expect another attack on Singapore, proposed a second, larger attack. British Special Operations approved it, and Lyon went to England to check on all the latest materials and equipment. There he examined a large minelaying submarine, the Porpoise, and tried out a Sleeping Beauty (SB), a 13-foot craft that could carry a man at four and one-half knots on the surface of the water or three and one-half knots underwater and had a range of 12 miles on a fully charged battery. The minelaying submarine and SBs were just what he wanted.  He returned to Australia, and at Careening Bay near Fremantle in Western Australia he began selecting and training volunteers for the operation he codenamed Rimau, the Malay word for tiger. He decided to use four of the men who had been on the Jaywick operation, Davidson, Page, Falls and Huston, and 17 other British and Australian sailors and commandos. Major Reginald Ingleton of the Royal Marines would go with them as an observer, but he quickly joined in as one of the team  Originally part of a much larger operation called Operation Hornbill, the aim of Rimau was to sink Japanese shipping by paddling the folboats in the dark and placing limpet mines on ships. It was originally intended that motorised semi-submersible canoes, known as "Sleeping Beauties", would be used to gain access to the harbour, however, they resorted to folboats.  After the raiding party's discovery by local Malay authorities, a total of thirteen men (including raid commander Lyon) were killed during battles with the Japanese military at a number of island locations or were captured and died of their wounds in Japanese captivity. In all, 10 of the team including Major Ingleton were brought as prisoners to Singapore. The Japanese considered them warriors in the spirit of Bushido, who had fought and had been captured, not surrendered. They treated them with respect. They were questioned repeatedly but not badly treated even thought they refused to tell anything of real importance about the operation. At the end of May 1945, a new Japanese commander in Singapore ordered that they be court-martialed. The court martial was held in early July, apparently against strong opposition by many in the Japanese military. The team was accused of being involved in a covert operation, not wearing full military uniform, and displaying the Japanese flag to confuse their enemies. They were found guilty and sentenced to death. On July 7, approximately one month before World War II in the Pacific came to an end, they were taken to a hill outside Singapore where they talked, smoked last cigarettes, and shook hands with one another. They were then ceremonially executed by the sword in the warrior tradition, their bodies falling into the graves prepared for them.  Later evidence stated it took guards more than half an hour to execute the men, sometimes requiring two or three blows to complete beheading. After the war, the bodies of the 10 were exhumed and, together with the bodies of those who died on the islands near Singapore, including Ivan Lyon, were buried in the Kranji war cemetery on Singapore Island.

Read in browser »

Jul 01, 2019 08:17 am

Major-General 'Titch' Houghton, who died January 1911 aged 98, was second-in-command of Royal Marine 40 Commando during the Second World War; captured in the Dieppe raid, he returned after three years as a PoW to take key roles with the commandos in peacetime.  'Titch' Houghton in 1947 Houghton's baptism of fire came on August 19 1942 during Operation Jubilee, when, in support of the main assault by Canadian troops, 40 Commando was to destroy port facilities at Dieppe and form a reserve. They crossed the Channel in the river gunboat Locust and arrived off Dieppe at about 0530, before disembarking into several LCAs (Landing Craft Assault). As Locust attempted to force the harbour entrance, she came under heavy fire from German batteries which the preliminary bombardment had failed to silence. She was repeatedly hit and her captain withdrew: meanwhile, the Canadians were pinned down on the beaches by heavy fire and barbed wire entanglements. 40 Commando was now ordered to land at the eastern end of the beach, but as the LCAs approached the shore they came under intense machine-gun and mortar fire. The commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel JP Phillips, ordered them to retreat back out to sea. In his landing craft, however, Houghton continued towards the shore, moving to the centre of the beach where he stormed the sands, his LCA blowing up behind him. "Ironically the doctor was our first casualty," Houghton noted. "But further casualties quickly followed. We advanced as far as the promenade wall, where progress was barred by thick wire entanglements swept by enemy fire. Pinned in this position with practically no cover, unable to move forward and without any means of returning by sea, we concentrated our efforts on inflicting as much damage as possible on the enemy positions. "Lacking any form of communication with our own forces, we continued until the official time of withdrawal had passed. The beach was strafed by our own aircraft at 1400 hours as part of the withdrawal programme, and it was just the luck of the draw that we found ourselves on the receiving end." Of 370 officers and men in 40 Commando, 76, including Phillips, were killed. Houghton, after fighting against overwhelming odds, was taken prisoner, though for many months he was reported dead. Later that year, in an act of vengeance, Hitler ordered commando prisoners to be shackled, and Houghton was handcuffed for 411 days. Afterwards he was awarded an MC for his bravery at Dieppe and for his endurance as a prisoner of war. Robert Dyer Houghton was born on March 7 1912 and educated at Haileybury. He joined the Royal Marines in 1930 and served in the battleship Malaya before qualifying as a small arms instructor. In 1935 he commanded an anti-aircraft battery of the Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisation (MNBDO) which, following the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, was deployed to Egypt to protect the Mediterranean Fleet at Alexandria. The MNBDO had been thrown together hurriedly and, while at Alexandria, trained together for the first time while on short notice to move to an advanced base in Crete. This situation was an excellent opportunity for a young officer, and Houghton, now 23, entered into his work with great enthusiasm, soon earning the respect of his men. By the time he returned to Chatham it was beginning to be recognised that he had considerable leadership potential. Soon after the outbreak of war Houghton was promoted captain and appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion, Royal Marines. He joined the RM Commando in early 1942. Liberated from his prison camp in Germany in 1945, Houghton was briefly commanding officer of 45 Commando until selected for the Army staff course. On completion he was delighted to be given command of 40 Commando. His leadership was tested when, in 1948, his Commando was sent to Haifa to cover the end of the Palestine Mandate and the withdrawal of British troops. Animosity towards the British from both Arabs and Jews was high, and there was looting and violence by extremists. Houghton's task was to keep the port open, and to mount searches to prevent arms being smuggled in from visiting ships. In April a series of vicious skirmishes took place between Jewish paramilitaries of the Haganah and Arab forces, and Houghton had to keep the peace while some 37,000 Arabs were evacuated from Haifa. He also had to house and feed large numbers of refugees who sought sanctuary in the dockyard. The final evacuation took place on June 30, smoothly and without incident, 40 Commando being the last to leave. For his outstanding leadership and distinguished service Houghton was appointed OBE. He was subsequently appointed to the Joint Services Staff College; as staff officer (Intelligence) to the Commander in Chief South Atlantic; commandant of the Commando School; and as director of the Royal Marines Reserve. In August 1957 Houghton was appointed Commander 3rd Commando Brigade, then based in Malta, where he devoted himself to bringing the brigade to a peak of efficiency and readiness for any emergency. He took his commandos to Libya, Turkey, Greece, Sardinia and Cyprus on a series of well-run exercises, and he oversaw pioneering trials of helicopters in commando assaults. There were numerous trouble spots in the Mediterranean and, when Malta itself suffered politically-inspired unrest, Houghton's brigade assisted the police in quelling riots and restoring calm. Houghton was insistent that the "fire brigade of the Mediterranean", as he called it, should be able to move anywhere at 12 hours' notice, and his orders were written for no fewer than 17 different scenarios. He was tested when, in anticipation of a political crisis threatening British nationals, the brigade's advance party flew to Libya, and the main body followed by sea. Before the main body landed, however, a greater problem arose in Cyprus, whereupon the rear party altered course and became the advance party to Cyprus, to be replaced in Malta by the advance party which returned from Libya. Houghton thrived on such situations. In 1959 he was appointed commanding officer of the Royal Marines in Deal and commandant of the Royal Marines School of Music. His last two appointments were as Director Joint Warfare Staff, and Major-General Royal Marines in Portsmouth. He was appointed CB and retired in 1964. In retirement he was president of 40 Commando Association and regularly attended reunions. In 1973 he was appointed a Deputy Lieutenant of Sussex, and from 1968 to 1978 was general secretary of the Royal United Kingdom Beneficent Association. Though naturally impetuous and forceful, Houghton was a more sensitive man than many appreciated. Like many short people, he unconsciously compensated by speaking louder than necessary, and if possible would seek a stair to stand on when communicating with others. Though he always maintained that the interests of the service came first, he was a devoted family man. With his sons, he built a model railway in his garden at Lewes which still runs today. He was president of the Gauge One Model Railway Association for more than 40 years during which time he increased its membership 10-fold. "Titch" Houghton (one of the few people in the Services given this nickname because he really was short) died on January 17. He married Dorothy Lyons in 1940. She died in 1995, and he is survived by their two sons and a daughter.

Read in browser »

|