|

|

|

|

Online Professional Development Sessions

|

|

|

Tonight at 9:00 PM EST

Seven Ways to Build Your Confidence as an Equitable Teacher

Presented by Pamela Seda and Kyndall Brown

Many teachers desire to have more equitable math classrooms, but don’t know where to start. In this presentation, participants will learn seven practical ways they can create more equitable math classrooms where all students get what they need to be successful. Pamela Seda and Kyndall Brown will share personal stories, tips from the classroom, and lessons they have learned on their journey to become more equitable math educators.

Click here to register for this webinar!

|

|

|

Coming Up on 9/7

Same But Different: A Language-based Routine to Promote Equity

Presented by Dr. Sue Looney

Join Sue Looney, creator of Same But Different Math, as she talks about the power of the Same But Different Math routine. Learn: Why Same But Different was created and how it helps students think powerfully; how to use Same But Different; How to create your own Same But Different images to meet your students' needs.

Click here to register for this webinar!

|

|

As the GMD Newsletter prepares for our first edition of the school year, we're sharing a few of our favorite articles from last year. We are currently gearing up for another great year of and looking for others to get involved. You can reach out on Twitter or send an email to globalmathdepartment@gmail.com.

|

|

From December 2020

Swimming in Water: Carceral Pedagogy in the Math Classroom

By: Lauren Baucom and Sara Rezvi

Poetry has a way of cutting to truth, of separating waves from the shorelines all the while observing both simultaneously. In his powerful poem, Guante notes that ‘white supremacy is not the shark, it is the water’. We swim in it, we are surrounded by it - these heady waters, this deep throbbing silence. Because of its constant presence, for many, it goes unnoticed, the water set as an unquestionable background. So, too, is the everpressing presence of carceral pedagogy in educational spaces. As writers of GMD, we refuse to participate in this silence. We mourn loudly. We bear witness deeply. We grieve. And we demand that these ideologies have no place within the mathematics classroom.

What is carceral pedagogy? How does it intersect with the mathematics classroom? What does it look, sound and feel like? Like the words of Guante, will we ever know it exists if we do not take time to recognize the waters in which we are constantly surrounded?

In a recent #Slowchat, Dr. Ilana Horn (@Ilana_horn) defined carcerality as “the physical domination and confinement of bodies in institutions, especially when they reinstate white supremacy.” Elsewhere, Dr. Bettina Love (@BLoveSoulPower), has discussed carcerality as systemic domination imposed by laws and enforced by incarceration. For the purpose of this piece, we define carceral pedagogy in the mathematics classroom to be the physical, mental, and social domination presented by the systems of white supremacy through laws, written and unwritten, that confine students’ bodies, minds, and spirits in the dehumanizing experiences of their mathematics education.

In this moment of virtual teaching when teachers have a voyeuristic ability to track, watch, and mandate policies through their surveillance apparatus of choice (ClassDojo, Zoom, Google Meets, etc), we’ve experienced how EduTwitter has taken the purpose of education as a source of liberation and used this time and space to incarcerate students’ minds and bodies through a system of compliance and oppression. Children are subjected to the ever-present disciplinary gaze of the carceral teacher. Some examples include: (1) when they can’t visit the bathroom in their own homes, (2) being forced to turn on cameras to be counted as present, and (3) being told not to eat in class when their caregiver offers them a snack. We must name these efforts of carcerality as they have quickly seeped into this new world of online learning during a pandemic. Rather than offering grace, compassion, and boundless love, carceral teachers have led the charge in creating spaces that invade privacy and invalidate the need to attend to growing bodies.

Simultaneously, we must revisit the mathematics classroom space of face-to-face teaching to understand how carcerality has been used in the past to oppress the bodies and minds of students.

In many classrooms, we have been sold the myth that students from low income areas require carceral style classroom pedagogy in order to succeed, and that without this type of oppression, they aren’t capable of doing the work. This kind of ideology is rooted in systems of white supremacy and dehumanization. We reject the narrative that the carceral teacher (who often is white) alone knows what is best for families and children of color. It is not the children that are lacking, but the carceral teacher.

There has been much research to show how students of color, specifically Black girls, have been denied their right to joyfully belong in math spaces. Using the ocrdata.ed.gov site, we can find countless examples of the literal barriers that imprison students to classes that are unworthy of their brilliance. How is it possible that in a district where almost 4 out of 10 of the students enrolled are Black, that less than half are allowed entry into Calculus classrooms? What unwritten laws govern the body language of students who appear “deep in mathematical thought” versus those who are “lazy, unproductive, and unmotivated”, physically barring them from mathematical spaces? We find it interesting that these narratives begin for students of color at young ages and continue onward into adolescence, almost as if these ideas are baked into our societal consciousness - as if we are all swimming in it.

Carceral pedagogy is often thought of to be discipline-based classroom practice, but it is also curricular. With the constant reminder from textbooks that mathematics was created in Europe by White males and no one else, the lack of representation confines students’ minds and social identities. Texts such as Francis Su’s (@mathyawp) ‘Mathematics for Human Flourishing’ and Talithia Williams’ ‘Power in Numbers: The Rebel Women of Mathematics’ eloquently work to decenter this notion that mathematics has only ever been a Eurocentric endeavor rather than a Human one. Elsewhere, I (Sara) along with my co-authors, have argued that mathematics, just like literacy, needs to have its own set of windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors.

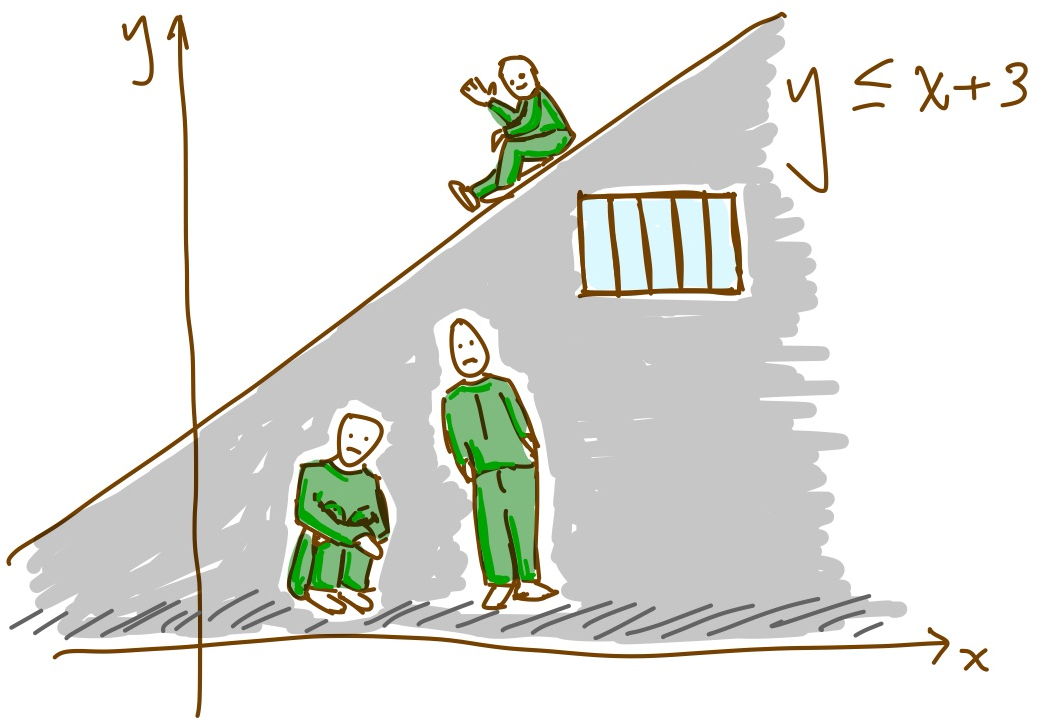

Another example of carcerality that appears in the mathematics curriculum occurs when a teacher requires a particular method of solving, rather than being open to the expansive, liberatory solving process that mathematics encourages.

Carceral classrooms are about control; when we try to control students’ thinking we create a low/no-trust environment with students that entraps their minds and eliminates the need for creativity, ingenuity, and authentic, original thought.

How is it that this meme can be so readily found when we describe math classrooms? That this concept of illegality in alternative thinking is synonymous with math classrooms, rather than the liberatory experience we know mathematics to be?

In closing, we reflect on the immediacy and urgency of Arundathi Roy’s quote. The pandemic is a portal. How we swim through it or whether we drown in it, is up to us. Where it leads to is up to us. We engage deliberately in the practice of freedom dreaming, of imagining a world beyond the violence enacted upon children in mathematics classrooms.

We are swimming in rough waters these days, full of murky sediment, glimpsing blearily into the unknown void. We have named here the silence, the complicity of holding onto dysfunctional systems that dehumanize children in the name of carcerality, of disciplinary productivity that seeks to mandate how we engage in mathematics (and beyond) as human beings. We ask the reader to consider the following - If we are more aware of the water, is that enough? Is our awareness enough? Do we keep swimming? Or do we change the scope of our navigations?

|

|

From March 2021

Thursday (March 11) will be the 10th anniversary of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Despite its apparent "natural" cause-- the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami-- an independent investigative panel called Fukushima "a profoundly manmade disaster-- that could and should have been foreseen and prevented. And its effects could have been mitigated by a more effective human response" (Kurokawa, 2012). Its effects are still being lived by displaced people, sick workers, and animals designated for slaughter because they are no longer good to eat. Philosopher Alexis Shotwell writes about farmers who have chosen to stay/return to Fukushima to care for radioactive cattle, calling their work a form of "care-as-protest" against the systems and ideologies that suggest the human and animal lives affected by (manmade) disaster no longer matter.

Thursday will also be the first anniversary of the WHO declaring COVID a pandemic: another profoundly manmade disaster, despite its apparent "natural" (viral) cause, because of how humans have responded and failed to respond. As people continue to die at a pace nearly impossible to make sense of and properly grieve, other people have created memorials as a form of care, for those whose lives were truncated and for those who are mourning, and as a form of protest against the anonymization, minimization, and anesthetization-- the not mattering-- that happens when lives affected by (manmade) disaster are relegated to statistics.

For many people, the events of the past year have heightened questions about how to be a human in a hot mess of a world, and specifically, how to be a mathematics teacher. I have so appreciated the many brilliant posts in this newsletter exploring and pressing on what mathematics teachers can and should be doing (by @LBmathemagician, @Hkhodai, and @melvinmperalta especially) for their students, for themselves, and for our world. There are no simple answers, because we are all complicit (as participants, especially with institutional authority) in the disastrous systems that tell mathematics students-- especially BIPoC students for whom US public schools were not designed, students who identify or are identified as girls, students who are labeled or made disabled-- that they and their mathematicalness do not matter. And there are certainly no universal answers, because we all operate from who we are and where we are and how we are uniquely, and what's right for one of us may not be right for another. But that does not mean there are no responses.

For my dissertation, I had the opportunity to spend a year observing how two veteran mathematics teachers "do what [they] can-- recognizing that what [they] can do, on its own, will never be enough" (Shotwell, 2016) to singlehandedly disrupt or dismantle the manmade disasters we are all living through. And what I found in what they do prompted me to think about a concept philosophers call response-ability. More than just a play on words, response-ability is a way of being that emphasizes what responses are made possible by your responses, and what responses are made possible by those responses, and so on.

For example, one of the teachers described getting to know students as a process of constantly trying out new ways of interacting with individual students: "is this something that makes [a student] smile when I say it? Is it something that makes them laugh when I say it? Is it something that makes them cringe when I say it?" In other words, what student responses are made possible by what you say and do, and what kind of further responses do those responses enable from you? Responses matter because they are how we show what matters, and what matters to us is often revealed by responses we aren't able to deliberate about in advance. When a student turns off their Zoom camera in the middle of class, do we mention it publicly, privately, in the moment, later, or at all? When a student interrupts a classmate, do we ignore it? Correct the behavior? Embrace the contribution? What student responses are made possible by each of these responses-- and what further responses are then made possible for you?

This past year I know many people have sought meaningful ways to enact their values that Black Lives Matter, that migrant lives matter, that incarcerated lives matter, that elderly and immunocompromised lives matter. We can post signs or statements, we can design lesson plans, we can speak up in meetings, we can vote, we can certainly do many more things. But also, how can your in-the-moment responses show students that they matter? That their thinking matters, their mathematical ideas matter, but also, even if they don't have any ideas they feel like sharing in the moment, mathematical or not, that they matter?

Written by Grace Chen @graceachen

|

|

From June 2021

A Call to Action: How Will YOU Push for Liberation in Mathematics?

– Brandie E. Waid ( @MathTeach_BEW)

Content Warning: Gun Violence; Murder; Violence against Trans, Queer, and BIPOC Communities

For many folx, June 12th of this year came and went as just another day. For me, as a queer Latina originally from Florida, this date was a time of grief and reflection. On this day five years ago, 49 beautiful souls—almost all queer and Latinx—were lost to a senseless act of hate and violence in the Pulse nightclub shooting. I spent this day reflecting on the violent acts, both small and large, that queer folx continue to experience in the United States every single day. In relation to large scale acts of violence, this year has been particularly difficult, especially for trans folx in our country, as evidenced by the 100+ anti-trans bills that have been proposed across state legislatures and the record number of transgender and gender non-conforming folx (almost all Black and/or Latinx) that have been murdered since Jan 1, 2021.

In addition to these large scale acts of violence, most queer folx continue to report experiencing small scale-acts of violence (or microagressions) on a regular basis. These include the use of homophobic and transphobic language in everyday conversations, the expectation to “act straight” or “pass” as cisgender for the comfort of those who do not identify as queer, denials/skepticism of queer folx’s experiences of homophobia and transphobia, the general misunderstandings that persist around what it means to be HIV positive, the belief of many religious folx that queer identity is immoral, the erasure of queer identity in many historical and other contexts, the inability to select the appropriate gender identity and/or sexuality on legal, medical, and other forms, and so on. Sadly, this violence is not new to queer folx, who have seen our humanity debated, stolen, and cut short throughout history. These attitudes persist today, as we saw in February when congress debated the passage of the Equality Act on the floor of the House of Representatives. BIPOC and trans folx within the queer community are especially vulnerable to this violence, even within the queer community itself, where many white, cis queers argue for a “respectable” version of queer identity that excludes BIPOC and trans folx from political priorities and the larger community.

As I reflected on this continued violence against my community, I began to think about the ways in which this violence manifests in mathematics teaching and learning. As noted by Dr. Rochelle Gutierrez, “violence...is regularly perpetuated (knowingly and unknowingly) against students, teachers, faculty, and members of society through mathematical practices, policies, and structures.” For queer students, this may take a number of forms, some of which are outlined below:

- Erasure of queer identity in mathematics problems - Positive representations of LGBTQ+ people in curricular materials has been found as linked to greater positive outcomes for LGBTQ+ students in grades K-12, yet only ⅓ of LGBTQ+ students surveyed for the 2019 National Climate Survey reported seeing any LGBTQ+ representation in their school curriculum. Of those that did report being exposed to LGBTQ+ representation only 48.8% reported those LGBTQ+ representations were presented in a positive manner. In mathematics, the numbers are even more abysmal , with 0.7% of LGBTQ+ students reporting having seen any LGBTQ+ representation in their math classes and of those, only 3.6% reporting the inclusion of positive LGBTQ+ representations. As a queer person, this lack of representation feels a little like looking into a mirror that seems to work for other folx, but for some reason isn’t showing me my reflection. Because of this, I’m not surprised by the underrepresentation of queer folx in STEM. If you don’t see your reflection in a mirror, you’re likely to think something is wrong with that mirror and go in search of another one...one that will show that you do, indeed, exist.

- Overemphasis on efficiency and rigid procedures in mathematics teaching and learning - Growing up as a closeted queer child, I was drawn to mathematics because I thought it was “cut and dry” and “safe.” If I followed the procedures my teacher taught me, I would succeed. These procedures felt more identifiable and easier to follow than the gender roles and heteronormative rules of society, which I often could not identify or understand, and that I seemed to constantly be getting wrong in my youth. This view of mathematics proved detrimental to me as I began to move through my mathematics career. It created within me extreme anxiety about stepping “outside the lines,” and being vulnerable by presenting solution methods or ideas that were in any way creative or novel. This view of mathematics, much like the debilitating threat of someone discovering my queer identity, limited me as a mathematical thinker, often triggering anxiety that was detrimental to my mental and mathematical well-being. It was not until I “came out” that I was able to begin shedding my extreme anxieties in these areas and begin considering creative, non-normative expressions in both my everyday life and in my mathematical thinking. While I cannot speak to the experience of all queer folx, I can imagine that for many of us the rigidity that is often found in mathematics classrooms can be both appealing and suffocating in a way that intrinsically ties mathematical identity to queer identity.

- Reinforcement of gender norms in the mathematics classroom; mathematics operating as masculine and white - As noted by Luis Leyva, mathematics is a “White and heteronormatively masculinized space.” The way that students enact (or conceal) their identities in mathematics is heavily influenced by this historical framing of mathematics. The way students and teachers communicate knowledge and what counts as knowledge is traditionally limited by the white, heteronormative, masculine nature of mathematics. These limitations back queer students and students of color into a corner, often limiting the ways in which they may express their humanity in connection with mathematics teaching and learning.

- Tracking, bullying, and dropout rates of LGBTQ+ youth- We often talk about tracking (or ability grouping) in terms of a gatekeeping measure that keeps BIPOC students from pursuing higher levels of mathematics. This is the case for queer students as well, who are less likely to successfully complete Algebra II than their non-queer peers. While the reasons that cause this are no doubt complex (and linked to the issues outlined above and below), this is further complicated by the fact that more than 80% of LGBTQ+ students surveyed indicate that they have been harassed, bullied, or assaulted at school within the last year. As a result, LGBTQ+ students are reported as having higher rates of absenteeism and of dropping out of school, establishing, again, that the school is a violent and exclusionary space for queer youth.

- Fear of discussing gender and sexuality in mathematics or the view that such topics are irrelevant - Two questions that I’m often asked are “Is it really appropriate to talk about sexuality in schools?” and “Aren’t kids too young to know how they identify?” I’ve responded to these questions in some of my previous work. In my view, both of these questions stem from teachers’ fears - fears about not being knowledgeable enough to talk about LGBTQ+ people and issues and fear of receiving pushback from administrators, parents, and the community. The thing about fear is that when we don’t talk about something because we are afraid to, students notice. It creates a culture in which those topics are taboo, and when the thing you are afraid of talking about is LGBTQ+ identity, it makes people taboo and breeds more fear. This sort of fear further perpetuates the general ignorance of folx surrounding LGBTQ+ people, and the violence LGBTQ+ folx are subjected to every day.

- Lack of (or limited) attention to queer students and their needs in social justice mathematics initiatives - A lot of attention has been given to social justice mathematics in recent years, yet relatively few lessons or initiatives have focused on the injustices faced by LGBTQ+ people, both presently and historically. For example, out of several of the books I currently own on teaching mathematics for social justice, only one contains lessons (two lessons, to be exact) that acknowledge the existence of LGBTQ+ people, much less focus on LGBTQ+ issues. Similarly, when we look at the social justice goals of our professional organizations, such as NCTM, LGBTQ+ students are never recognized as a vulnerable group worthy of inclusion in our equity and social justice initiatives.

As mathematics educators, we must begin taking active roles in preventing the reproduction of this violence in our mathematics classrooms. How do we do that? In a blog post I wrote in February, I outlined a few ways that mathematics educators can begin to take action in support of their LGBTQ+ students. In addition to those items, I also believe it is important for us to recognize that we are but single individuals. In order to change the landscape of hate and violence our schools inflict upon LGBTQ+ students, BIPOC students, disabled students, and students from other marginalized groups, we must push for systemic change. Pushing for systemic change can come in a multitude of forms, including petitioning your local school and/or district to adopt more inclusive policies and curriculum and writing to your state and local representatives to support laws that protect our students from traditionally marginalized groups and oppose those that cause them harm.

Another means of taking action is to turn to our professional organizations, such as NCTM, NCSM, AERA, and AMTE, and urge them to adopt policies and practices that better support BIPOC, queer, disabled, multilngual, and undocumented educators and students. These organizations often proclaim social justice orientations but continue to be experienced as violent spaces for many queer and BIPOC members. There are a number of ways these organizations can be restructured to live up to their social justice ideals, such as diversifying their Board of Directors and Executive Suites, providing membership and conference scholarships to BIPOC and queer educators, taking a more active approach in seeking out BIPOC and queer folx that do equity work and paying them for their labor, and so on.

In addition to adopting internal policies and practices that better support BIPOC, queer, disabled, multilngual, and undocumented educators and students, we can urge these organizations to play a more active role in our political climate. These professional organizations have powerful platforms from which they can condemn harmful legislation such as the anti-trans laws, voter suppression laws, and critical race theory bans that are sweeping across state legislatures. Each of these laws impacts our students and our schools, as is indicated in this open letter to NCTM, NCSM, AERA, & AMTE (which you can sign here!). These organizations must commit to nuanced approaches to resisting these laws and use their immense lobbying power to prevent the passage of harmful legislation. We can and must urge them to do so.

As a queer Latinx mathematics educator, I dream of a day when our most vulnerable students (BIPOC, queer, and the like) see themselves reflected in our mathematics curriculum. I dream of a day in which these students are free to be themselves without fear or consequence, free of the violence inflicted upon them in mathematics classrooms. I dream of a liberated mathematics education, one that sees and celebrates every student for who they are; one that centers joy and humanity. But this dream of mine cannot be realized alone. Each and every one of us must be committed to this work. So my question to each of you is - will you join me?

Acknowledgement: Shout out to my dear friend Arundhati Velamur for all the last minute edits to this piece (and oh so many others in the past)!

|

|

|

From November 2020

Numbers and Sense

Last week in Washington, D.C., I overheard a conversation on the train between two strangers:

A: I just don't believe COVID is real.

B: But the news is reporting that cases in the U.S. are rising. How could you ignore that?

A: Where are the infected people? The news is just reporting numbers. Numbers aren't the facts! Numbers aren't the infection. The people have the infection! Show me the people!

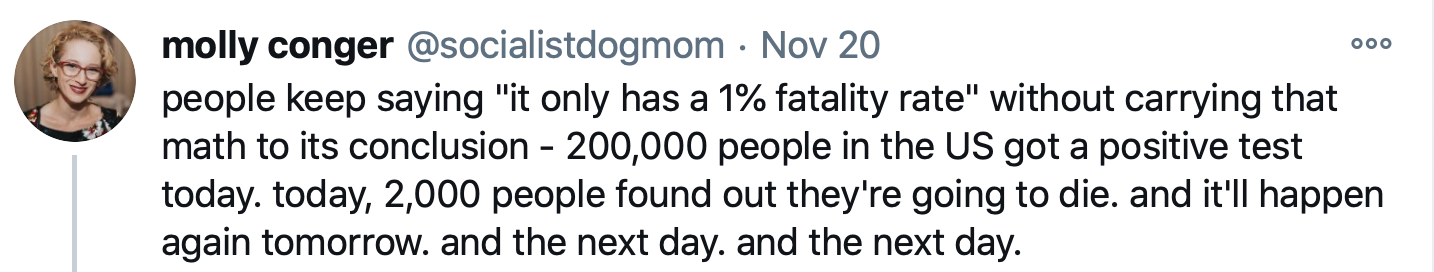

I've been thinking about that conversation. I've been thinking about numbers and about how we process and react to them. I’ve been thinking about tweets like these:

And about podcast episodes like Dispatch 1: Numbers from Radiolab, which talks about the numbers connected to COVID.

With the pandemic came a national conversation largely spoken in the language of mathematics. Education scholar Bill Barton describes mathematics as any system for dealing with the quantitative, relational, and spatial aspects of human experience. How are people dealing with the quantities, relationships, and spatial life of COVID? What are people doing or not doing with this knowledge?

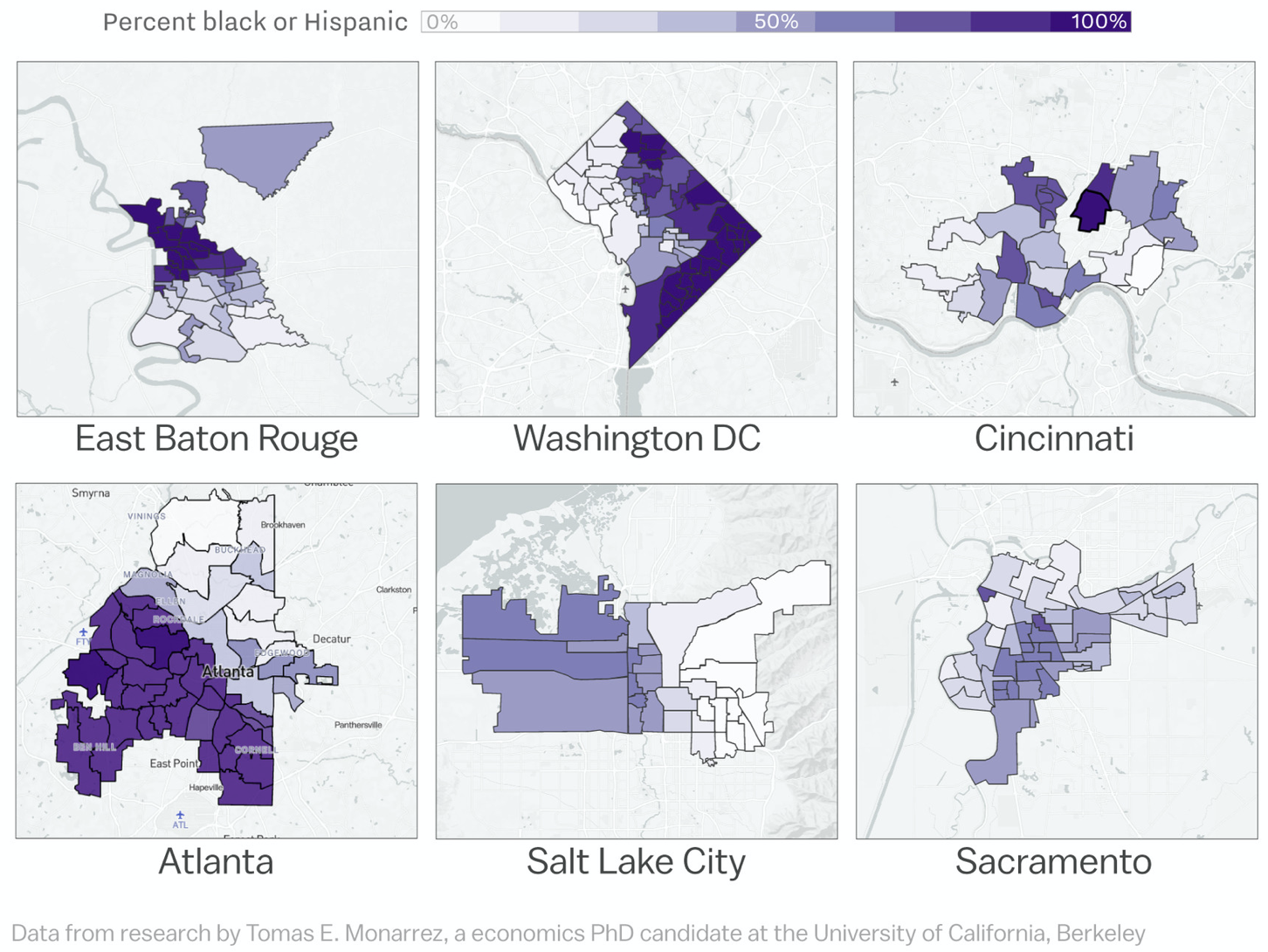

We teach students how to do all kinds of things to quantities, relationships, and space. They learn how to represent them as objects, cut these objects up and piece them back together, and reconfigure them into increasingly abstract forms. But often, quantities, relationships, and space are not abstract. They point to things that touch our lives such as whether COVID cases are low enough that schools can remain open or how district borders affect racial segregation in schools.

How often are teachers helping students process the quantities, relationships, and spaces in their lives? In a literature class, students talk about their personal reactions to a Toni Morrison novel. In an art class, students talk about the meanings and intentions behind their work. But in a traditional math class, it’s like students learn how to cook without ever being asked what they think about the food.

To be fair, not every mathematical concept needs to be tied to a “real-world” context. But numbers can matter, and numbers don’t speak for themselves. Numbers can make us feel. They can make us act. They can change how we see ourselves and one another. How this happens is not automatic. Like everything else, our relationship to numbers is a learned phenomena.

The Slow Reveal Graphs by Jenna Laib (@jennalaib) is one way we can promote quantitative and spatial literacy while also giving students space to talk about how certain numbers and graphs impact them and why. This instructional routine does a nice job promoting “number sense” by giving equal weight to “number” and “sense”. The slow reveal graphs take a rigorous approach to data analysis. But at the same time, there is nothing inherently objective about numbers. Numbers are always accompanied by a regime of perception that makes some things “make sense” and other things unrecognizable. For instance, consider how a “1% fatality rate” can make the world look a certain way depending on how you think about it while also hiding information about issues such as race and class. The slow reveal graph routine invites students to think deeply about this connection between numbers and perception.

Maybe the numbers aren’t the facts. But we can’t avoid our responsibility to engage with numbers and ask where they come from, how they make us feel, and when they lead us to act. Mathematical sense making is not a purely technical affair. Instead, it’s a practice also concerned with ethics and responsibility and a willingness to challenge what even constitutes “common sense”. This is the essence of mathematical sense making, which gives students the agency and hope to decide what is sensible beyond the boundaries of what society already tries to impose on them.

@melvinmperalta

|

|

|

In 2019, I taught Contemporary Mathematics in a medium security men's correctional facility. Prior to that experience, I had never been inside a correctional facility, nor had I had significant conversations with anyone who had been incarcerated. Following that experience, I started corresponding with inmates through the Prison Mathematics Project, and I am writing this piece with the following in mind.

- Through teaching and corresponding about math with incarcerated folks, I have uncovered a core principle of my teaching philosophy: "Everyone deserves to find freedom and joy in mathematics."

- Incarceration and feelings of isolation while learning math create barriers to learning that are unique to the incarcerated

In my Contemporary Mathematics course, I had fully intended to give students my best active learning pedagogy in every class. But one day I arrived, waited with colleagues for almost 2 hours for correction officers to clear the instructors to go to our classrooms, and found an exhausted group of men. There had clearly been An Incident, and on a “normal” campus, I would have rescheduled our class. On this campus, rescheduling was impossible for logistical reasons, but also — my students wanted to be there, even exhausted, because our classroom was a different kind of space for them. Did we do the small group, active inquiry exercises I had planned? Reader, we did not. I covered some material with a (minimally) active lecture, and saved time at the end for just... sitting there. Doing math, not doing math, whatever.

“Every day that I wake up and go about my life I try not to allow the present circumstances that I’ve created for myself to determine the passions and the future I want to see myself in,” writes Christopher Jackson, an inmate whose correspondence with Francis Su inspired the book Mathematics for Human Flourishing. Su and other educators are working toward a vision of liberation while — and through — learning mathematics (see also @ATN_1863). This past summer, I attended a workshop on Embodying Liberatory Practices in the Classroom put on by the NYU Metro Center ( @metronyu). This workshop was important to my own continued growth as a professor for many reasons, but in particular, it gave words to a feeling that had been growing as I experienced and learned more about math in prison. It's not just students in traditional classrooms who deserve liberation; math learners in prisons deserve a liberatory classroom, too.  To fully see our incarcerated students’ circumstances, we have to understand who is in prison. Given the demographics of the incarcerated in the US, rehumanizing mathematics and trauma-informed pedagogy are necessarily linked with liberatory mathematics in prisons. (In my 30+ years of being in classrooms as a learner or teacher, my Contemporary Math class had the most diverse group of students along the axes of age, ethnicity, and race.) But the math pedagogy that works for joyful, collaborative, community-oriented mathematics in “normal” classrooms doesn't seem to translate neatly to prison. Barriers to learning combine in ways that are specific to being in prison; a pedagogy for teaching in prison must anticipate and respond to those.

What I felt then (and still feel now) is that there must be more to teaching in prison than just doing my best and adapting on the fly. There is surely a network of people who are thinking hard about mathematics education for incarcerated people. And they’re not just thinking about how classrooms are a place for incarcerated people to learn mathematics, but they’re thinking about how teaching and learning mathematics is a way to affirm the humanity of incarcerated folks. And I want in!

So, dear Global Mathematicians, I hope you'll correspond with me about the following questions:

- Who is thinking through/has thought through/wants to think through math pedagogy specific to correctional facilities? How do we keep in touch?

- What body of literature is out there that can help support improvements to prison education programs (including but not limited to improvements to, e.g., the interested instructor)? How does the interested practitioner find resources and opportunities like The Inside Out Center?

What is our homework as abolitionists — keeping carceral pedagogy out of our schools, keeping folks out of prison, ensuring that classrooms and prisons are safe places for those who inhabit them, and increasing access to liberatory mathematics? How can we be effective together where we might be ineffective individually? |

|

|

Check Out the Webinar Archives

Click here for the archives, get the webinars in podcast form, or visit our YouTube Channel to find videos of past sessions and related content.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|