Foreword This Week

January 28, 2021

Reviewer Dontaná McPherson-Joseph Interviews Colin Rafferty, Author of Execute the Office: Essays with Presidents

All those years ago, when Donald Trump first became POTUS, do you remember the chatter about how the office would change him, would humble his fast-talking celebrity schtick, that once the massive sense of responsibility sunk in, he would pivot and mature into the role?

How’d that work out? Michelle Obama had it exactly right when she said the presidency doesn’t change you, it magnifies who you are, and indeed, over the course of four years, we watched in real time as President Trump’s combative personality quickly entered warp speed and accelerated from there. He did it his way—and how!

But some presidents do grow into the office and outperform expectations, while many others wither under the pressure and a handful even die from the demands of the job.

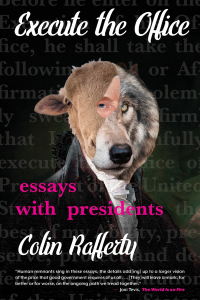

This week, with the help of Colin Rafferty, we have an opportunity to better understand what the presidency does to the men who hold the office. The author of Execute the Office: Essays with Presidents, Colin agreed to take a few questions from Dontaná McPherson-Joseph—she the pen behind the Jan/Feb 2021 Foreword review of his book.

Kudos to Baobab Press for publishing this important book. And lastly, we’re hoping you might lend us a hand by sharing this interview with others who might be interested in this and the other books we cover in Foreword This Week. Your help in growing our community of independently published book lovers is so appreciated. Here’s a link for them to sign up: https://www.forewordreviews.com/subscriptions/email/

Dontaná, please take it from here.

There is a lot of information in these essays, and the extensive notes and reading list reflect the level of research. Was the research and writing process ever overwhelming?

Not too often, actually, because the process slowly built up to writing a book. Initially, I just wanted to be able to name all the presidents in order—it felt like a gap in my knowledge. That was in the summer of 2009, and I realized that if I read a presidential biography each month, then I could have all of them read by the time the 2012 election took place. After that, it seemed like I should do something with all that trivia rattling around, so I started writing essays about the presidents.

Sometimes, research ended up being an excuse not to write. I remember telling my wife that I was thinking about driving to the church in Virginia where George and Martha Washington had been married, because I wasn’t quite sure how to write about him. She said that I could do that, or I could write the essay with what I had.

I appreciated that you didn’t shy away from the hard realities of American history. What was your thought process when choosing which information to share? How did you decide how to distill the lives of these people?

I tried to think about the various roles that the president plays, both officially and unofficially. For instance, he’s supposed to deliver a State of the Union address, so I should have an essay about that, which was how I found a shape for the James K. Polk essay. The president can issue pardons, so who issued notable pardons? Well, Jimmy Carter pardoned all the men who left the country to avoid Vietnam, so that seems like a good spot for him. The president throws out the first pitch, so I should find someone who I can connect to baseball, but also to competition—that’s George Bush, Senior.

Sometimes I wanted to connect my own history to American History. I come from a long line of Midwestern New Deal Democrats, so the FDR essay was a way to discuss the impact the president’s decisions can have on ordinary citizens. As a late Gen Xer, my childhood was shaped by Reagan’s rhetoric and performance, so I wrote a script in which he and I (and John Wayne) converse. In 2008, I heard but didn’t see Obama during a campaign stop, so that became a way to talk about how we both perceive the president both as a person and as a figurehead.

Ultimately, for each president, I had a twofold goal in mind: show them as portraying some aspect of this bigger-than-life job, and show them as unique, fallible humans.

When sitting down to write, what was the biggest influence or inspiration for each president’s format?

I’m always intrigued by seeing people in public—back when we could hang out in public—who are working on laptops. I always assume they’re working on the Great American Book. I wanted in on that game, so I decided that I was going to write this book in public.

I would take a notebook and some pens, and then start walking. I’d walk, thinking about the presidents and some ideas very loosely—something like “Franklin Pierce / alcoholism / medical history / loss”—and then, eventually, I’d start to figure out a few sentences. At that point, I’d head for the nearest coffee shop and buy a cup, which I figured got me somewhere between a half hour and forty-five minutes to write. With that kind of pressure and without the distraction of the internet, I’d usually manage to put together a first draft.

The essay for James Madison, “Paul Jennings Dreams of the Burning of Washington,” is the only essay not written directly about the president, but around him. Madison doesn’t show up. Why? What about Madison made him, more or less, unworthy to show up in his own essay, and instead made you focus on Paul Jennings?

Madison is a fascinating, complex figure who really ought to be talked about as much as Washington and Jefferson, so it’s ironic that he’s the president who gets the boot from his own essay. Paul Jennings, though, was an equally interesting character, and the metaphor of the White House’s furnishings getting rescued not by the president, but by women, enslaved people, and working men was really powerful to me. Plus, putting Jennings at the front of an essay was a way of acknowledging that he was also the author of a book about the presidents, since he wrote one of the first White House memoirs.

My favorite line in the entire collection is “This job murders men.” Has your opinion of the presidency changed or evolved since you first started writing these essays, whether in the context of being possibly the most murderous job in America or just in general?

I’m paraphrasing, but Obama once said that the easy decisions never reached his desk—someone underneath him knew what to do and did it—so everything he dealt with was a major concern. I think, for a lot of us, there are these stretches of American history that feel blurry—between the Revolution and the Civil War, between the Civil War and the Great Depression—so it was a revelation to me to realize that we’ve been in one crisis or another for the vast majority of our existence. The presidency just seems like an impossible job to ask one person to do, and yet it’s a system that has worked in large part for a very long time.

What was the most surprising thing you learned?

As a writer, the most surprising thing I learned was that it was tremendously difficult to write about the big figures with lots of information about them—George Washington was the last president I wrote about. Trivia-wise, though, so much stuff: the Marquis de Lafayette gave pet alligators to the young John Quincy Adams! Jimmy Carter was the first president born in a hospital! Rutherford B. Hayes had the wildest White House china!

When the book comes out, we will be past the inauguration of President Biden, but still reeling from and grappling with the effects of the storming of the United States Capitol. Do you think your essays change in conversation with that event? How so or why not?

In many of the inaugural addresses, the presidents mention the peaceful transfer of power between parties, and how it’s such a common thing in America that we forget the miracle of it. The attack on the Capitol changes the essays in how they show that miracle, charging it, I hope, with something that lessens our cynicism about the presidency and the government. It’s such a fragile thing, ultimately, and I hope that the essays show that for all the flaws of the people, all the flaws of the system and its structures, representative democracy is an idea that remains worth our time and attention.

Featured Reviews of the Week

Christian/Romance

Roots of Wood and Stone: Sedgwick County Chronicles, by Amanda Wen (Kregel Publications): “With a resonant, alternating timeline that highlights the past’s continuing influence on the present, Roots of Wood and Stone is a satisfying, moving novel that combines ancestral stories with a new romance.” Review by Karen Rigby.

Literary Fiction

The Portrait, by Ilaria Bernardini (Pegasus): “Comprised of short vignettes that move in swift, restless succession, the novel addresses the past and the present alongside one another, so that time becomes a spiral that closes in on itself. The Portrait is a meditative, illuminating novel that pushes the boundaries of love and art.” Starred review by Mari Carlson.

Literary/LGBTQ+ Fiction

Art Is Everything, by Yxta Maya Murray (TriQuarterly Books): “Portraying an unsuccessful artist’s glide into washout and reinvention after capitalism’s unequal demands erode their ability to create, Yxta Maya Murray’s novel Art Is Everything is a candid critique of society’s usurious relationship with BIPOC, queer, and working-class women artists.” Review by Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers.

Crafts & Hobbies

Field Guide to Knitted Birds: Over 50 Handmade Projects to Liven Up Your Roost, by Carlos Zachrison and Arne Nerjordet (Trafalgar Square Books): “There are birds with embroidery inspired by Mexican textiles, birds that look like birds from nature, birds with traditional sweater patterns worked onto them, and even an Arne bird and a Carlos bird, both with glasses and hair. The book’s “designer” birds are embellished with sequins, feathers, and beads, with instructions for attaching embellishments and forming the birds’ legs and feet.” Starred review by Sarah White.

General Fiction

Minus Me, by Mameve Medwed (Alcove Press): “Medwed’s appealing characters make Minus Me a thoughtful story about the promises that family members make to one another, about what it truly means to live, and about what people hope to pass on after they die.” Review by Jaime Herndon.