Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – an extraordinary love letter from Balzac, Susan Sontag on the commodification of wisdom, humanistic hope for the present from 1930, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – an extraordinary love letter from Balzac, Susan Sontag on the commodification of wisdom, humanistic hope for the present from 1930, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

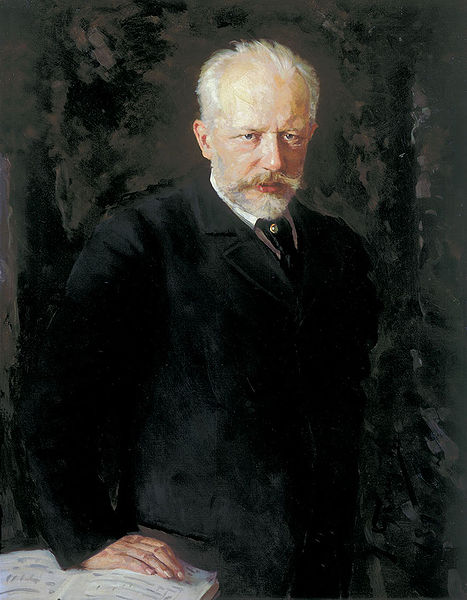

"A self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood."

I recently stumbled upon a recurring theme articulated by both Jack White and Nick Cave, a concept that flies in the face of our cultural mythology about how creativity works – the idea that just showing up and doing the work, or what Jonah Lehrer calls "grit," the same quality that Ira Glass says separates mere good taste from great work and Anne Lamott believes is the secret to telling a good story – is just as important as the notion of "inspiration" in the creative process.

I recently stumbled upon a recurring theme articulated by both Jack White and Nick Cave, a concept that flies in the face of our cultural mythology about how creativity works – the idea that just showing up and doing the work, or what Jonah Lehrer calls "grit," the same quality that Ira Glass says separates mere good taste from great work and Anne Lamott believes is the secret to telling a good story – is just as important as the notion of "inspiration" in the creative process.

All of this reminded me of a fantastic letter legendary composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote to his benefactress, Nadezhda von Meck, dated March 17th, 1878, and found in the 1905 volume The Life & Letters of Pete Ilich Tchaikovsky (public domain):

Do not believe those who try to persuade you that composition is only a cold exercise of the intellect. The only music capable of moving and touching us is that which flows from the depths of a composer's soul when he is stirred by inspiration. There is no doubt that even the greatest musical geniuses have sometimes worked without inspiration. This guest does not always respond to the first invitation. We must always work, and a self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood. If we wait for the mood, without endeavouring to meet it half-way, we easily become indolent and apathetic. We must be patient, and believe that inspiration will come to those who can master their disinclination.

Do not believe those who try to persuade you that composition is only a cold exercise of the intellect. The only music capable of moving and touching us is that which flows from the depths of a composer's soul when he is stirred by inspiration. There is no doubt that even the greatest musical geniuses have sometimes worked without inspiration. This guest does not always respond to the first invitation. We must always work, and a self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood. If we wait for the mood, without endeavouring to meet it half-way, we easily become indolent and apathetic. We must be patient, and believe that inspiration will come to those who can master their disinclination.

A few days ago I told you I was working every day without any real inspiration. Had I given way to my disinclination, undoubtedly I should have drifted into a long period of idleness. But my patience and faith did not fail me, and to-day I felt that inexplicable glow of inspiration of which I told you; thanks to which I know beforehand that whatever I write to-day will have power to make an impression, and to touch the hearts of those who hear it. I hope you will not think I am indulging in self-laudation, if I tell you that I very seldom suffer from this disinclination to work. I believe the reason for this is that I am naturally patient. I have learnt to master myself, and I am glad I have not followed in the steps of some of my Russian colleagues, who have no self-confidence and are so impatient that at the least difficulty they are ready to throw up the sponge. This is why, in spite of great gifts, they accomplish so little, and that in an amateur way.

Here is Jack White, echoing – unwittingly, no doubt – Tchaikovsky:

Inspiration and work ethic – they ride right next to each other.... Not every day you're gonna wake up and the clouds are gonna part and rays from heaven are gonna come down and you're gonna write a song from it. Sometimes, you just get in there and just force yourself to work, and maybe something good will come out.

Inspiration and work ethic – they ride right next to each other.... Not every day you're gonna wake up and the clouds are gonna part and rays from heaven are gonna come down and you're gonna write a song from it. Sometimes, you just get in there and just force yourself to work, and maybe something good will come out.

:: SHARE ::

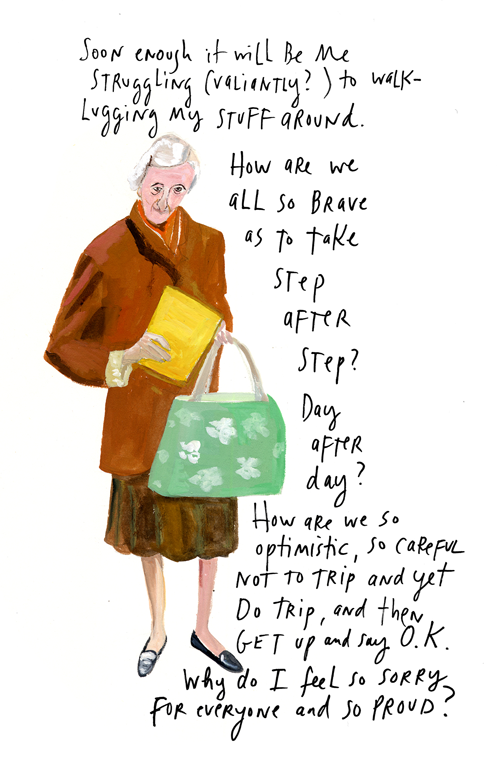

"How are we so optimistic, so careful Not to trip and yet Do trip, and then GET up and say O.K."

In this wonderful short video, Maira Kalman – the remarkable artist, prolific author, unmatched storyteller, and one of my favorite hearts and minds in the world – shares some wisdom on identity, happiness, and existence. Watch and take notes.

The idea that you'd have to say 'goodbye' to all this – even though it's infuriating and maddening and frightening and horrible, some of the time – is even more infuriating and maddening and horrible: How do you spend this time without perpetually being so broken-hearted about saying the eventual goodbye? I usually say, in the end, okay, it's love and it's work – what else could there possibly be?

The idea that you'd have to say 'goodbye' to all this – even though it's infuriating and maddening and frightening and horrible, some of the time – is even more infuriating and maddening and horrible: How do you spend this time without perpetually being so broken-hearted about saying the eventual goodbye? I usually say, in the end, okay, it's love and it's work – what else could there possibly be?

Speaking to the fluidity of character and the myth of fixed personality, Kalman observes:

How do you know who you are? There are many parts to who you are, so there isn't one static place. And then, the other part of that is that things keep changing.

How do you know who you are? There are many parts to who you are, so there isn't one static place. And then, the other part of that is that things keep changing.

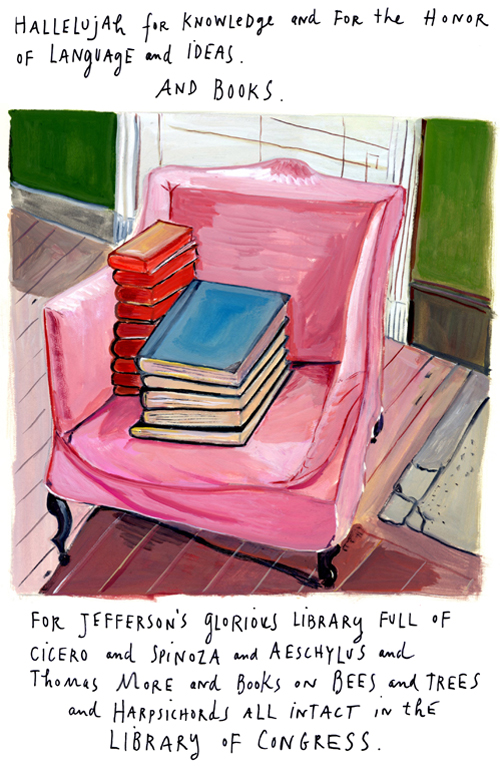

Here are some of the beautiful, poignant quotes Kalman reads and shows from her published works.

From And The Pursuit of Happiness:

From The Principles of Uncertainty:

How are we so optimistic, so careful Not to trip and yet Do trip, and then GET up and say O.K. Why do I feel so sorry for everyone and so PROUD?

How are we so optimistic, so careful Not to trip and yet Do trip, and then GET up and say O.K. Why do I feel so sorry for everyone and so PROUD?

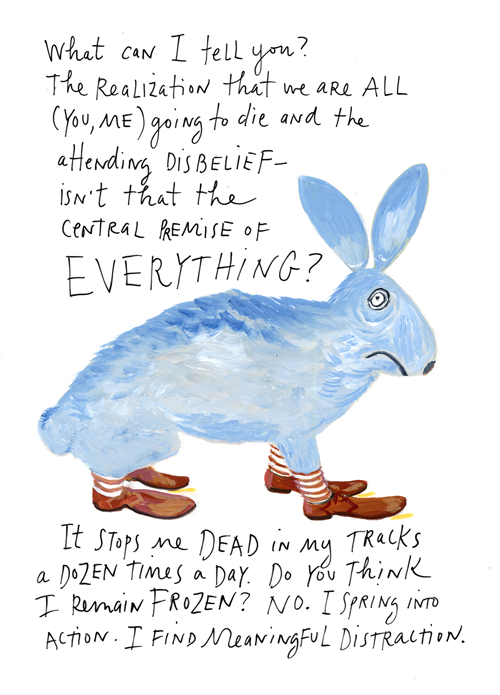

What can I tell you? The realization that we are ALL (you, me) going to die and the attending disbelief – isn't that the central promise of EVERYTHING? It stops me DEAD in my tracks a DOZEN times a day. Do you think I remain FROZEN? NO. I spring into action. I find meaningful distraction.

What can I tell you? The realization that we are ALL (you, me) going to die and the attending disbelief – isn't that the central promise of EVERYTHING? It stops me DEAD in my tracks a DOZEN times a day. Do you think I remain FROZEN? NO. I spring into action. I find meaningful distraction.

:: SHARE / WATCH ::

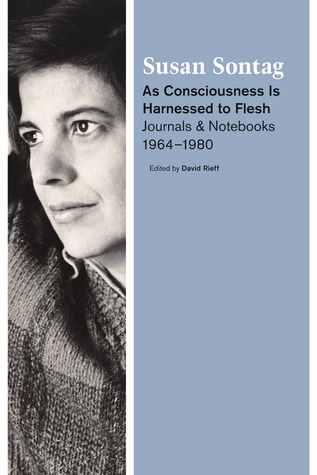

The newly released volume of Susan Sontag's diaries, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964-1980 (public library), from whence Sontag's thoughtful meditations on censorship and aphorisms came, is an absolute treasure trove of rare insight into one of the greatest minds in modern history. Among the tome's greatest gifts are Sontag's thoughts on the art, craft, and ideology of writing.

The newly released volume of Susan Sontag's diaries, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964-1980 (public library), from whence Sontag's thoughtful meditations on censorship and aphorisms came, is an absolute treasure trove of rare insight into one of the greatest minds in modern history. Among the tome's greatest gifts are Sontag's thoughts on the art, craft, and ideology of writing.

Unlike more prescriptive takes, like previously examined advice by Kurt Vonnegut, John Steinbeck, and David Ogilvy, Sontag's reflections are rather meditative – sometimes turned inward, with introspective curiosity, and other times outward, with a lens on the broader literary landscape – yet remarkably rich in cultural observation and universal wisdom on the writing process, somewhere between Henry Miller's creative routine, Jack Kerouac's beliefs and techniques, George Orwell's four motives for writing, and E. B. White's vision for the responsibility of the writer.

Gathered here are the most compelling and profound of Sontag's thoughts on writing, arranged chronologically and each marked with the date of the respective diary entry.

I have a wider range as a human being than as a writer. (With some writers, it's the opposite.) Only a fraction of me is available to be turned into art. (8/8/64)

I have a wider range as a human being than as a writer. (With some writers, it's the opposite.) Only a fraction of me is available to be turned into art. (8/8/64)

Words have their own firmness. The word on the page may not reveal (may conceal) the flabbiness of the mind that conceived it. > All thoughts are upgrades – get more clarity, definition, authority, by being in print – that is, detached from the person who thinks them.

Words have their own firmness. The word on the page may not reveal (may conceal) the flabbiness of the mind that conceived it. > All thoughts are upgrades – get more clarity, definition, authority, by being in print – that is, detached from the person who thinks them.

A potential fraud – at least potential – in all writing. (8/20/64)

Writing is a little door. Some fantasies, like big pieces of furniture, won't come through. (8/30/64)

Writing is a little door. Some fantasies, like big pieces of furniture, won't come through. (8/30/64)

Science fiction –

Science fiction –

Popular mythology for contemporary negative imagination about the impersonal (11/1/64)

Greatest subject: self seeking to transcend itself (Middlemarch, War and Peace)

Greatest subject: self seeking to transcend itself (Middlemarch, War and Peace)

Looking for self-transcendence (or metamorphosis) – the cloud of unknowing that allows perfect expressiveness (a secular myth for this) (undated loose sheets, 1965)

Kafka the last story-teller in 'serious' literature. Nobody has known where to go from there (except imitate him) (undated loose sheets, 1965)

Kafka the last story-teller in 'serious' literature. Nobody has known where to go from there (except imitate him) (undated loose sheets, 1965)

John Dewey – 'The ultimate function of literature is to appreciate the world, sometimes indignantly, sometimes sorrowfully, but best of all to praise when it is luckily possible.' (1/25/65)

John Dewey – 'The ultimate function of literature is to appreciate the world, sometimes indignantly, sometimes sorrowfully, but best of all to praise when it is luckily possible.' (1/25/65)

I think I am ready to learn how to write. Think with words, not with ideas. (3/5/70)

I think I am ready to learn how to write. Think with words, not with ideas. (3/5/70)

'Writing is only a substitute [sic] for living.' – Florence Nightingale (12/18/70)

'Writing is only a substitute [sic] for living.' – Florence Nightingale (12/18/70)

French, unlike English: a language that tends to break when you bend it. (6/21/72)

French, unlike English: a language that tends to break when you bend it. (6/21/72)

A writer, like an athlete, must 'train' every day. What did I do today to keep in 'form'? (7/5/72)

A writer, like an athlete, must 'train' every day. What did I do today to keep in 'form'? (7/5/72)

In 'life,' I don't want to be reduced to my work. In 'work,' I don't want to be reduced to my life.

In 'life,' I don't want to be reduced to my work. In 'work,' I don't want to be reduced to my life.

My work is too austere

My life is a brutal anecdote (3/15/73)

The only story that seems worth writing is a cry, a shot, a scream. A story should break the reader's heart

The only story that seems worth writing is a cry, a shot, a scream. A story should break the reader's heart

[…]

The story must strike a nerve – in me. My heart should start pounding when I hear the first line in my head. I start trembling at the risk. (6/27/73)

I'm now writing out of rage – and I feel a kind of Nietzschean elation. It's tonic. I roar with laughter. I want to denounce everybody, tell everybody off. I go to my typewriter as I might go to my machine gun. But I'm safe. I don't have to face the consequences of 'real' aggressivity. I'm sending out colis piégés ['booby-trapped packages'] to the world. (7/31/73)

I'm now writing out of rage – and I feel a kind of Nietzschean elation. It's tonic. I roar with laughter. I want to denounce everybody, tell everybody off. I go to my typewriter as I might go to my machine gun. But I'm safe. I don't have to face the consequences of 'real' aggressivity. I'm sending out colis piégés ['booby-trapped packages'] to the world. (7/31/73)

The solution to a problem – a story that you are unable to finish – is the problem. It isn't as if the problem is one thing and the solution something else. The problem, properly understood = the solution. Instead of trying to hide or efface what limits the story, capitalize on that very limitation. State it, rail against it. (7/31/73)

The solution to a problem – a story that you are unable to finish – is the problem. It isn't as if the problem is one thing and the solution something else. The problem, properly understood = the solution. Instead of trying to hide or efface what limits the story, capitalize on that very limitation. State it, rail against it. (7/31/73)

Talking like touching

Talking like touching

Writing like punching somebody (8/14/73)

To be a great writer:

To be a great writer:

know everything about adjectives and punctuation (rhythm)

have moral intelligence – which creates true authority in a writer (2/6/74)

'Idea' as method of instant transport away from direct experience, carrying a tiny suitcase.

'Idea' as method of instant transport away from direct experience, carrying a tiny suitcase.

'Idea' as a means of miniaturizing experience, rendering it portable. Someone who regularly has ideas is – by definition – homeless.

Intellectual is a refugee from experience. In Diaspora.

What's wrong with direct experience? Why would one ever want to flee it, by transforming it – into a brick? (7/25/74)

Weakness of American poetry – it's anti-intellectual. Great poetry has ideas. (6/14/76)

Weakness of American poetry – it's anti-intellectual. Great poetry has ideas. (6/14/76)

Not only must I summon the courage to be a bad writer – I must dare to be truly unhappy. Desperate. And not save myself, short-circuit the despair.

Not only must I summon the courage to be a bad writer – I must dare to be truly unhappy. Desperate. And not save myself, short-circuit the despair.

By refusing to be as unhappy as I truly am, I deprive myself of subjects. I've nothing to write about. Every topic burns. (6/19/76)

The function of writing is to explode one's subject – transform it into something else. (Writing is a series of transformations.)

The function of writing is to explode one's subject – transform it into something else. (Writing is a series of transformations.)

Writing means converting one's liabilities (limitations) into advantages. For example, I don't love what I'm writing. Okay, then – that's also a way to write, a way that can produce interesting results. (11/5/76)

'All art aspires to the condition of music' – this utterly nihilistic statement rests at the foundation of every moving camera style in the history of the medium. But it is a cliché, a 19th c[entury] cliché, less an aesthetic than a projection of an exhausted state of mind, less a world view than a world weariness, less a statement of vital forms than an expression of sterile decadence. There is quite another pov [point of view] about what 'all art aspires to' – that was Goethe's, who put the primary art, the most aristocratic one, + the one art that cannot be made by the plebes but only gaped at w[ith] awe, + that art is architecture. Really great directors have this sense of architecture in their work – always expressive of immense line of energy, unstable + vital conduits of force. (undated, 1977)

'All art aspires to the condition of music' – this utterly nihilistic statement rests at the foundation of every moving camera style in the history of the medium. But it is a cliché, a 19th c[entury] cliché, less an aesthetic than a projection of an exhausted state of mind, less a world view than a world weariness, less a statement of vital forms than an expression of sterile decadence. There is quite another pov [point of view] about what 'all art aspires to' – that was Goethe's, who put the primary art, the most aristocratic one, + the one art that cannot be made by the plebes but only gaped at w[ith] awe, + that art is architecture. Really great directors have this sense of architecture in their work – always expressive of immense line of energy, unstable + vital conduits of force. (undated, 1977)

One can never be alone enough to write. To see better. (7/19/77)

One can never be alone enough to write. To see better. (7/19/77)

Two kinds of writers. Those who think this life is all there is, and want to describe everything: the fall, the battle, the accouchement, the horse-race. That is, Tolstoy. And those who think this life is a kind of testing-ground (for what we don't know – to see how much pleasure + pain we can bear or what pleasure + pain are?) and want to describe only the essentials. That is, Dostoyevsky. The two alternatives. How can one write like T. after D.? The task is to be as good as D. – as serious spiritually, + then go on from there. (12/4/77)

Two kinds of writers. Those who think this life is all there is, and want to describe everything: the fall, the battle, the accouchement, the horse-race. That is, Tolstoy. And those who think this life is a kind of testing-ground (for what we don't know – to see how much pleasure + pain we can bear or what pleasure + pain are?) and want to describe only the essentials. That is, Dostoyevsky. The two alternatives. How can one write like T. after D.? The task is to be as good as D. – as serious spiritually, + then go on from there. (12/4/77)

Only thing that counts are ideas. Behind ideas are [moral] principles. Either one is serious or one is not. Must be prepared to make sacrifices. I'm not a liberal. (12/4/77)

Only thing that counts are ideas. Behind ideas are [moral] principles. Either one is serious or one is not. Must be prepared to make sacrifices. I'm not a liberal. (12/4/77)

When there is no censorship the writer has no importance.

When there is no censorship the writer has no importance.

So it's not so simple to be against censorship. (12/7/77)

Imagination: – having many voices in one's head. The freedom for that. (5/27/78)

Imagination: – having many voices in one's head. The freedom for that. (5/27/78)

Language as a found object (2/1/79)

Language as a found object (2/1/79)

Last novelist to be influenced by, knowledgeable about science was [Aldous] Huxley

Last novelist to be influenced by, knowledgeable about science was [Aldous] Huxley

One reason [there are] no more novels – There are no exciting theories of relation of society to self (soc[iological], historical, philosophical)

Not SO – no one is doing it, that's all (undated, March 1979)

There is a great deal that either has to be given up or be taken away from you if you are going to succeed in writing a body of work (undated, March 1979)

There is a great deal that either has to be given up or be taken away from you if you are going to succeed in writing a body of work (undated, March 1979)

To write one must wear blinkers. I've lost my blinkers.

To write one must wear blinkers. I've lost my blinkers.

Don't be afraid to be concise! (3/10/79)

A failure of nerve. About writing. (And about my life – but never mind.) I must write myself out of it.

A failure of nerve. About writing. (And about my life – but never mind.) I must write myself out of it.

If I am not able to write because I'm afraid of being a bad writer, then I must be a bad writer. At least I'll be writing.

Then something else will happen. It always does.

I must write every day. Anything. Everything. Carry a notebook with me at all times, etc.

I read my bad reviews. I want to go to the bottom of it – this failure of nerve (7/19/79)

The writer does not have to write. She must imagine that she must. A great book: no one is addressed, it counts as cultural surplus, it comes from the will. (3/10/80)

The writer does not have to write. She must imagine that she must. A great book: no one is addressed, it counts as cultural surplus, it comes from the will. (3/10/80)

Ordinary language is an accretion of lies. The language of literature must be, therefore, the language of transgression, a rupture of individual systems, a shattering of psychic oppression. The only function of literature lies in the uncovering of the self in history. (3/15/80)

Ordinary language is an accretion of lies. The language of literature must be, therefore, the language of transgression, a rupture of individual systems, a shattering of psychic oppression. The only function of literature lies in the uncovering of the self in history. (3/15/80)

The love of books. My library is an archive of longings. (4/26/80)

The love of books. My library is an archive of longings. (4/26/80)

Making lists of words, to thicken my active vocabulary. To have puny, not just little, hoax, not just trick, mortifying, not just embarrassing, bogus, not just fake.

Making lists of words, to thicken my active vocabulary. To have puny, not just little, hoax, not just trick, mortifying, not just embarrassing, bogus, not just fake.

I could make a story out of puny, hoax, mortifying, bogus. They are a story. (4/30/80)

As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh is exquisite in its entirety – I couldn't recommend it more heartily.

:: SHARE ::

In an age obsessed with practicality, productivity, and efficiency, I frequently worry that we are leaving little room for abstract knowledge and for the kind of curiosity that invites just enough serendipity to allow for the discovery of ideas we didn't know we were interested in until we are, ideas that we may later transform into new combinations with applications both practical and metaphysical.

In an age obsessed with practicality, productivity, and efficiency, I frequently worry that we are leaving little room for abstract knowledge and for the kind of curiosity that invites just enough serendipity to allow for the discovery of ideas we didn't know we were interested in until we are, ideas that we may later transform into new combinations with applications both practical and metaphysical.

This concern, it turns out, is hardly new. In The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge (PDF), originally published in the October 1939 issue of Harper's, American educator Abraham Flexner explores this dangerous tendency to forgo pure curiosity in favor of pragmatism – in science, in education, and in human thought at large – to deliver a poignant critique of the motives encouraged in young minds, contrasting those with the drivers that motivated some of history's most landmark discoveries.

We hear it said with tiresome iteration that ours is a materialistic age, the main concern of which should be the wider distribution of material goods and worldly opportunities. The justified outcry of those who through no fault of their own are deprived of opportunity and a fair share of worldly goods therefore diverts an increasing number of students from the studies which their fathers pursued to the equally important and no less urgent study of social, economic, and governmental problems. I have no quarrel with this tendency. The world in which we live is the only world about which our senses can testify. Unless it is made a better world, a fairer world, millions will continue to go to their graves silent, saddened, and embittered. I have myself spent many years pleading that our schools should become more acutely aware of the world in which their pupils and students are destined to pass their lives. Now I sometimes wonder whether that current has not become too strong and whether there would be sufficient opportunity for a full life if the world were emptied of some of the useless things that give it spiritual significance; in other words, whether our conception of what .is useful may not have become too narrow to be adequate to the roaming and capricious possibilities of the human spirit.

We hear it said with tiresome iteration that ours is a materialistic age, the main concern of which should be the wider distribution of material goods and worldly opportunities. The justified outcry of those who through no fault of their own are deprived of opportunity and a fair share of worldly goods therefore diverts an increasing number of students from the studies which their fathers pursued to the equally important and no less urgent study of social, economic, and governmental problems. I have no quarrel with this tendency. The world in which we live is the only world about which our senses can testify. Unless it is made a better world, a fairer world, millions will continue to go to their graves silent, saddened, and embittered. I have myself spent many years pleading that our schools should become more acutely aware of the world in which their pupils and students are destined to pass their lives. Now I sometimes wonder whether that current has not become too strong and whether there would be sufficient opportunity for a full life if the world were emptied of some of the useless things that give it spiritual significance; in other words, whether our conception of what .is useful may not have become too narrow to be adequate to the roaming and capricious possibilities of the human spirit.

Flexner goes on to explore the question from two points of view – the scientific and the humanistic, or spiritual – and recounts a conversation with legendary entrepreneur and Kodak founder George Eastman, in which the two debate who "the most useful worker in science in the world" is. Eastman points to radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi, but Flexner stumps Eastman by arguing that, despite his invention, Marconi's impact on improving human life was "practically negligible." His explanation bespeaks a familiar subject – combinatorial creativity and the additive nature of invention:

Mr. Eastman, Marconi was inevitable. The real credit for everything that has been done in the field of wireless belongs, as far as such fundamental credit can be definitely assigned to anyone, to Professor Clerk Maxwell, who in 1865 carried out certain abstruse and remote calculations in the field of magnetism and electricity.... Other discoveries supplemented Maxwell's theoretical work during the next fifteen years. Finally in 1887 and 1888 the scientific problem still remaining – the detection and demonstration of the electromagnetic waves which are the carriers of wireless signals – was solved by Heinrich Hertz, a worker in Helmholtz's laboratory in Berlin. Neither Maxwell nor Hertz had any concern about the utility of their work; no such thought ever entered their minds. They had no practical objective. The inventor in the legal sense was of course Marconi, but what did Marconi invent? Merely the last technical detail, mainly the now obsolete receiving device called coherer, almost universally discarded.

Mr. Eastman, Marconi was inevitable. The real credit for everything that has been done in the field of wireless belongs, as far as such fundamental credit can be definitely assigned to anyone, to Professor Clerk Maxwell, who in 1865 carried out certain abstruse and remote calculations in the field of magnetism and electricity.... Other discoveries supplemented Maxwell's theoretical work during the next fifteen years. Finally in 1887 and 1888 the scientific problem still remaining – the detection and demonstration of the electromagnetic waves which are the carriers of wireless signals – was solved by Heinrich Hertz, a worker in Helmholtz's laboratory in Berlin. Neither Maxwell nor Hertz had any concern about the utility of their work; no such thought ever entered their minds. They had no practical objective. The inventor in the legal sense was of course Marconi, but what did Marconi invent? Merely the last technical detail, mainly the now obsolete receiving device called coherer, almost universally discarded.

Hertz and Maxwell could invent nothing, but it was their useless theoretical work which was seized upon by a clever technician and which has created new means for communication, utility, and amusement by which men whose merits are relatively slight have obtained fame and earned millions. Who were the useful men? Not Marconi, but Clerk Maxwell and Heinrich Hertz. Hertz and Maxwell were geniuses without thought of use. Marconi was a clever inventor with no thought but use.

Flexner goes on to contend that the work of Hertz and Maxwell is exemplary of the motives underpinning all instances of monumental scientific discovery, bringing to mind Richard Feynman's timeless wisdom.

[Hertz and Maxwell] had done their work without thought of use and that throughout the whole history of science most of the really great discoveries which had ultimately proved to be beneficial to mankind had been made by men and women who were driven not by the desire to be useful but merely the desire to satisfy their curiosity.

[Hertz and Maxwell] had done their work without thought of use and that throughout the whole history of science most of the really great discoveries which had ultimately proved to be beneficial to mankind had been made by men and women who were driven not by the desire to be useful but merely the desire to satisfy their curiosity.

Upon Eastman's surprise, Flexner defends the idea of curiosity as a guiding principle in science and innovation:

Curiosity, which may or may not eventuate in something useful, is probably the outstanding characteristic of modern thinking. It is not new. It goes back to Galileo, Bacon, and to Sir Isaac Newton, and it must be absolutely unhampered. Institutions of learning should be devoted to the cultivation of curiosity and the less they are deflected by considerations of immediacy of application, the more likely they are to contribute not only to human welfare but to the equally important satisfaction of intellectual interest which may indeed be said to have become the ruling passion of intellectual life in modern times.

Curiosity, which may or may not eventuate in something useful, is probably the outstanding characteristic of modern thinking. It is not new. It goes back to Galileo, Bacon, and to Sir Isaac Newton, and it must be absolutely unhampered. Institutions of learning should be devoted to the cultivation of curiosity and the less they are deflected by considerations of immediacy of application, the more likely they are to contribute not only to human welfare but to the equally important satisfaction of intellectual interest which may indeed be said to have become the ruling passion of intellectual life in modern times.

This lament, alas, is timelier than ever. As Columbia biological sciences professor Stuart Firestein reminds us in the excellent Ignorance: How It Drives Science, grant applications for scientific research are now routinely denied on the grounds of being "curiosity-driven" – a term used in a pejorative sense whereas, ironically, it should describe the highest aspiration of science, something many a great scientist can speak to.

Flexner goes on to give several more examples, pointing to the work of Einstein, Faraday, Gauss, and other legendary scientists, then sums it all up with a thoughtful disclaimer:

I am not for a moment suggesting that everything that goes on in laboratories will ultimately turn to some unexpected practical use or that an ultimate practical use is its actual justification. Much more am I pleading for the abolition of the word 'use,' and for the freeing of the human spirit. To be sure, we shall thus

free some harmless cranks. To be sure, we shall thus waste some precious dollars. But what is infinitely more important is that we shall be striking the shackles off the human mind and setting it free for the adventures which in our own day have, on the one hand, taken Hale and Rutherford and Einstein and their peers millions upon millions of miles into the uttermost realms of space and, on the other, loosed the boundless energy imprisoned in the atom. What Rutherford and others like Bohr and Millikan have done out of sheer curiosity in the effort to understand the construction of the atom has released forces which may transform human life; but this ultimate and unforeseen and unpredictable practical result is not offered as a justification for Rutherford or Einstein or Millikan or Bohr or any of their peers.

I am not for a moment suggesting that everything that goes on in laboratories will ultimately turn to some unexpected practical use or that an ultimate practical use is its actual justification. Much more am I pleading for the abolition of the word 'use,' and for the freeing of the human spirit. To be sure, we shall thus

free some harmless cranks. To be sure, we shall thus waste some precious dollars. But what is infinitely more important is that we shall be striking the shackles off the human mind and setting it free for the adventures which in our own day have, on the one hand, taken Hale and Rutherford and Einstein and their peers millions upon millions of miles into the uttermost realms of space and, on the other, loosed the boundless energy imprisoned in the atom. What Rutherford and others like Bohr and Millikan have done out of sheer curiosity in the effort to understand the construction of the atom has released forces which may transform human life; but this ultimate and unforeseen and unpredictable practical result is not offered as a justification for Rutherford or Einstein or Millikan or Bohr or any of their peers.

Further:

With the rapid accumulation of 'useless' or theoretic knowledge a situation has been created in which it has become increasingly possible to attack practical

problems in a scientific spirit. Not only inventors, but 'pure' scientists have indulged in this sport. I have mentioned Marconi, an inventor, who, while a benefactor to the human race, as a matter of fact merely 'picked other men's brains.' Edison belongs to the same category.

With the rapid accumulation of 'useless' or theoretic knowledge a situation has been created in which it has become increasingly possible to attack practical

problems in a scientific spirit. Not only inventors, but 'pure' scientists have indulged in this sport. I have mentioned Marconi, an inventor, who, while a benefactor to the human race, as a matter of fact merely 'picked other men's brains.' Edison belongs to the same category.

[…]

Ehrlich, fundamentally speculative in his curiosity, turned fiercely upon the problem of syphilis and doggedly pursued it until a solution of immediate practical use – the discovery of salvarsan – was found. The discoveries of insulin by Banting for use in diabetes and of liver extract by Minot and Whipple for use in pernicious anemia belong in the same category: both were made by thoroughly scientific men, who realized that much 'useless' knowledge had been piled up by men unconcerned with its practical bearings, but that the time was now ripe to raise practical questions in a scientific manner.

Flexner sums up the idea that, as Steve Jobs famously observed, "creativity is just connecting things" and, as Mark Twain put it, "all ideas are second-hand" in this beautiful articulation, adding to history's greatest definitions of science:

Thus it becomes obvious that one must be wary in attributing scientific discovery wholly to anyone person. Almost every discovery has a long and precarious history. Someone finds a bit here, another a bit there. A third step succeeds later and thus onward till a genius pieces the bits together and makes the decisive contribution. Science, like the Mississippi, begins in a tiny rivulet in the distant forest. Gradually other streams swell its volume. And the roaring river that bursts the dikes is formed from countless sources.

Thus it becomes obvious that one must be wary in attributing scientific discovery wholly to anyone person. Almost every discovery has a long and precarious history. Someone finds a bit here, another a bit there. A third step succeeds later and thus onward till a genius pieces the bits together and makes the decisive contribution. Science, like the Mississippi, begins in a tiny rivulet in the distant forest. Gradually other streams swell its volume. And the roaring river that bursts the dikes is formed from countless sources.

He extends this into a vision for the future of education, touching on points we've more recently seen made by contemporary education reform thinkers like Sir Ken Robinson and John Seely Brown:

Over a period of one or two hundred years the contributions of professional schools to their respective activities will probably be found to lie, not so much in the training of men who may to-morrow become practical engineers or practical lawyers or practical doctors, but rather in the fact that even in the pursuit of strictly practical aims an enormous amount of apparently useless activity goes on. Out of this useless activity there come discoveries which may well prove of infinitely more importance to the human mind and to the human spirit than the accomplishment of the useful ends for which the schools were founded.

Over a period of one or two hundred years the contributions of professional schools to their respective activities will probably be found to lie, not so much in the training of men who may to-morrow become practical engineers or practical lawyers or practical doctors, but rather in the fact that even in the pursuit of strictly practical aims an enormous amount of apparently useless activity goes on. Out of this useless activity there come discoveries which may well prove of infinitely more importance to the human mind and to the human spirit than the accomplishment of the useful ends for which the schools were founded.

The prescience of Flexner's insights on education continues, eventually circling back to the whole of the human condition:

The subject which I am discussing has at this moment a peculiar poignancy. In certain large areas – Germany and Italy especially – the effort is now being

made to clamp down the freedom of the human spirit. Universities have been so reorganized that they have become tools of those who believe in a special political, economic, or racial creed. Now and then a thoughtless individual in one of the few democracies left in this world will even question the fundamental importance of absolutely untrammeled academic freedom. The real enemy of the human race is not the fearless and irresponsible thinker, be he right or wrong. The real enemy is the man who tries to mold the human spirit so that it will not dare to spread its wings, as its wings were once spread in Italy and Germany, as well as in Great Britain

and the United States.

The subject which I am discussing has at this moment a peculiar poignancy. In certain large areas – Germany and Italy especially – the effort is now being

made to clamp down the freedom of the human spirit. Universities have been so reorganized that they have become tools of those who believe in a special political, economic, or racial creed. Now and then a thoughtless individual in one of the few democracies left in this world will even question the fundamental importance of absolutely untrammeled academic freedom. The real enemy of the human race is not the fearless and irresponsible thinker, be he right or wrong. The real enemy is the man who tries to mold the human spirit so that it will not dare to spread its wings, as its wings were once spread in Italy and Germany, as well as in Great Britain

and the United States.

[…]

Justification of spiritual freedom goes, however, much farther than originality whether in the realm of science or humanism, for it implies tolerance throughout the range of human dissimilarities. In the face of the history of the human race what can be more silly or ridiculous than likes or dislikes founded upon race or religion? Does humanity want symphonies and paintings and profound scientific truth, or does it want Christian symphonies, Christian paintings, Christian science, or Jewish symphonies, Jewish paintings, Jewish science, or Mohammedan or Egyptian or Japanese or Chinese or American or German or Russian or Communist or Conservative contributions to and expressions of the infinite richness of the human soul?

For more of Flexner's timeless, timelier than ever insights on education and the human spirit, see Iconoclast: Abraham Flexner and a Life in Learning.

:: SHARE ::