Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – the annual special highlighting the most read and shared Brain Pickings articles of the year – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

Hey <<Name>>! If you missed last week's edition – the annual special highlighting the most read and shared Brain Pickings articles of the year – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation.

"To invent, you have to take the odd and the strange combination of the years of knowledge and experience."

In How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer (UK; public library), Debbie Millman (previously) sits down with 20 of today's most celebrated graphic designers to unravel the secrets of their creative process, work ethic, and general philosophy on life. The result is a kind of modern-day equivalent of the 1942 gem Anatomy of Inspiration, presenting a rare glimpse of the creative machinery behind some of today's most talented and influential designers through conversations that reveal in equal measure their purposeful brilliance and tender humanity.

In How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer (UK; public library), Debbie Millman (previously) sits down with 20 of today's most celebrated graphic designers to unravel the secrets of their creative process, work ethic, and general philosophy on life. The result is a kind of modern-day equivalent of the 1942 gem Anatomy of Inspiration, presenting a rare glimpse of the creative machinery behind some of today's most talented and influential designers through conversations that reveal in equal measure their purposeful brilliance and tender humanity.

One of the most stimulating interviews is with the inimitable Paula Scher – identity and branding goddess, Pentagram partner, maker of magnificent hand-drawn maps, tireless champion of combinatorial creativity – who echoes Thoreau in this beautiful, poetic definition of success:

If I get up every day with the optimism that I have the capacity for growth, then that's success for me.

If I get up every day with the optimism that I have the capacity for growth, then that's success for me.

Like many of history's greatest scientists, Scher speaks to the power of intuition and additive knowledge in sparking those creative Eureka! moments, stressing the importance of what novelist William Gibson has termed "personal micro-culture." She illustrates the point with an exquisite metaphor:

There's a certain amount of intuitive thinking that goes into everything. It's so hard to describe how things happen intuitively. I can describe it as a computer and a slot machine. I have a pile of stuff in my brain, a pile of stuff from all the books I've read and all the movies I've seen. Every piece of artwork I've ever looked at. Every conversation that's inspired me, every piece of street art I've seen along the way. Anything I've purchased, rejected, loved, hated. It's all in there. It's all on one side of the brain.

There's a certain amount of intuitive thinking that goes into everything. It's so hard to describe how things happen intuitively. I can describe it as a computer and a slot machine. I have a pile of stuff in my brain, a pile of stuff from all the books I've read and all the movies I've seen. Every piece of artwork I've ever looked at. Every conversation that's inspired me, every piece of street art I've seen along the way. Anything I've purchased, rejected, loved, hated. It's all in there. It's all on one side of the brain.

And on the other side of the brain is a specific brief that comes from my understanding of the project and says, okay, this solution is made up of A, B, C, and D. And if you pull the handle on the slot machine, they sort of run around in a circle, and what you hope is that those three cherries line up, and the cash comes out.

But rather than willing the cherries into alignment, the essence of creative alchemy, says Scher, is in allowing for unconscious processing – that intuitive incubation period, to use T.S. Eliot's term, that allows for all the combinatorial pieces gathered over years of being alive and awake to the world to click into place, to congeal into what we call "invention":

I am conscious of resolving the brief, but I don't think about it too hard. I allow the subconscious part of my brain to work. That's the accumulation of my whole life. That is what's going on in the other side of my brain, trying to align with this very logical brief.

I am conscious of resolving the brief, but I don't think about it too hard. I allow the subconscious part of my brain to work. That's the accumulation of my whole life. That is what's going on in the other side of my brain, trying to align with this very logical brief.

And I'm allowing that to flow freely, so that the cherries can line up in the slot machine. I don't know when that's going to happen. I've had periods of time when the cherries never line up, and that's scary, because then you have to rely on tricks you already have up your sleeve – the tricks in your knowledge from other jobs. And very often you rely on this.

But mostly what you want to do is invent. And to invent, you have to take the odd and the strange combination of the years of knowledge and experience on one side of the brain, and on the other side, the necessity for the brief to make sense. And you're drawing from that knowledge to make an analogy and to find a way to solve a problem, to find a means of moving forward – in a new way – things you've already done.

When you succeed, it's fantastic. It doesn't always happen. But every so often, you take a bunch of stuff from one side of your head, and a very logical list of stuff from the other side, and through that osmosis you're finding a new way to look at a problem and resolve a situation.

Perhaps George Lois was right, after all, when he stated that creativity is discovering ideas rather than "creating" them and John Cleese correctly defined it as "a way of operating" rather than a mystical talent.

How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer is fantastic in its entirety – highly recommended.

:: SHARE ::

NOTE: For email-friendliness, this lengthy article has been truncated. Read the full version online, with more highlights and excerpts from each book.

The final addition to this year's best-of reading lists – spanning art, design, philosophy and psychology, picturebooks, history, graphic novels and graphic nonfiction, food, and music – is a look at your favorite reads featured on Brain Pickings in 2012, based on an alchemy of various readership statistics and other data voodoo.

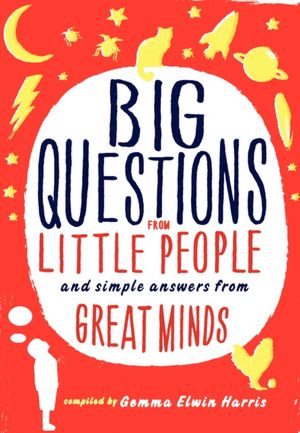

BIG QUESTIONS FROM LITTLE PEOPLE

BIG QUESTIONS FROM LITTLE PEOPLE

"If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch," Carl Sagan famously observed in Cosmos, "you must first invent the universe." The questions children ask are often so simple, so basic, that they turn unwittingly yet profoundly philosophical in requiring apple-pie-from-scratch type of answers. To explore this fertile intersection of simplicity and expansiveness, Gemma Elwin Harris asked thousands of primary school children between the ages of four and twelve to send in their most restless questions, then invited some of today's most prominent scientists, philosophers, and writers to answer them. The result is Big Questions from Little People & Simple Answers from Great Minds (public library), one of the best children's books of 2012 – a compendium of fascinating explanations of deceptively simple everyday phenomena, featuring such modern-day icons as Mary Roach, Noam Chomsky, Philip Pullman, Richard Dawkins, and many more, with a good chunk of the proceeds being donated to Save the Children, and also one of the best science books of 2012.

"If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch," Carl Sagan famously observed in Cosmos, "you must first invent the universe." The questions children ask are often so simple, so basic, that they turn unwittingly yet profoundly philosophical in requiring apple-pie-from-scratch type of answers. To explore this fertile intersection of simplicity and expansiveness, Gemma Elwin Harris asked thousands of primary school children between the ages of four and twelve to send in their most restless questions, then invited some of today's most prominent scientists, philosophers, and writers to answer them. The result is Big Questions from Little People & Simple Answers from Great Minds (public library), one of the best children's books of 2012 – a compendium of fascinating explanations of deceptively simple everyday phenomena, featuring such modern-day icons as Mary Roach, Noam Chomsky, Philip Pullman, Richard Dawkins, and many more, with a good chunk of the proceeds being donated to Save the Children, and also one of the best science books of 2012.

Alain de Botton explores why we have dreams:

Most of the time, you feel in charge of your own mind. You want to play with some Lego? Your brain is there to make it happen. You fancy reading a book? You can put the letters together and watch characters emerge in your imagination.

Most of the time, you feel in charge of your own mind. You want to play with some Lego? Your brain is there to make it happen. You fancy reading a book? You can put the letters together and watch characters emerge in your imagination.

But at night, strange stuff happens. While you’re in bed, your mind puts on the weirdest, most amazing and sometimes scariest shows. … In the olden days, people believed that our dreams were full of clues about the future. Nowadays, we tend to think that dreams are a way for the mind to rearrange and tidy itself up after the activities of the day. … Dreams show us that we’re not quite the bosses of our own selves.

My favorite answers are to the all-engulfing question, How do we fall in love? Author Jeanette Winterson offers this breathlessly poetic response:

You don't fall in love like you fall in a hole. You fall like falling through space. It’s like you jump off your own private planet to visit someone else’s planet. And when you get there it all looks different: the flowers, the animals, the colours people wear. It is a big surprise falling in love because you thought you had everything just right on your own planet, and that was true, in a way, but then somebody signalled to you across space and the only way you could visit was to take a giant jump. Away you go, falling into someone else’s orbit and after a while you might decide to pull your two planets together and call it home. And you can bring your dog. Or your cat. Your goldfish, hamster, collection of stones, all your odd socks. (The ones you lost, including the holes, are on the new planet you found.)

You don't fall in love like you fall in a hole. You fall like falling through space. It’s like you jump off your own private planet to visit someone else’s planet. And when you get there it all looks different: the flowers, the animals, the colours people wear. It is a big surprise falling in love because you thought you had everything just right on your own planet, and that was true, in a way, but then somebody signalled to you across space and the only way you could visit was to take a giant jump. Away you go, falling into someone else’s orbit and after a while you might decide to pull your two planets together and call it home. And you can bring your dog. Or your cat. Your goldfish, hamster, collection of stones, all your odd socks. (The ones you lost, including the holes, are on the new planet you found.)

And you can bring your friends to visit. And read your favourite stories to each other. And the falling was really the big jump that you had to make to be with someone you don’t want to be without. That’s it.

PS You have to be brave.

* * * MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK * * *

TINY BEAUTIFUL THINGS

TINY BEAUTIFUL THINGS

When an anonymous advice columnist by the name of "Dear Sugar" introduced herself on The Rumpus on March 11, 2010, she made her proposition clear: a "by-the-book common sense of Dear Abby and the earnest spiritual cheesiness of Cary Tennis and the butt-pluggy irreverence of Dan Savage and the closeted Upper East Side nymphomania of Miss Manners." But in the two-some years that followed, she proceeded to deliver something tenfold punchier, more honest, more existentially profound than even such an intelligently irreverent promise could foretell. This year, all of Sugar's no-bullshit, wholehearted wisdom on life's trickiest contexts – sometimes the simplest, sometimes the most complex, always the most deeply human – was released in Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Dear Sugar (UK; public library), along with several never-before-published columns, under Sugar's real name: Cheryl Strayed.

When an anonymous advice columnist by the name of "Dear Sugar" introduced herself on The Rumpus on March 11, 2010, she made her proposition clear: a "by-the-book common sense of Dear Abby and the earnest spiritual cheesiness of Cary Tennis and the butt-pluggy irreverence of Dan Savage and the closeted Upper East Side nymphomania of Miss Manners." But in the two-some years that followed, she proceeded to deliver something tenfold punchier, more honest, more existentially profound than even such an intelligently irreverent promise could foretell. This year, all of Sugar's no-bullshit, wholehearted wisdom on life's trickiest contexts – sometimes the simplest, sometimes the most complex, always the most deeply human – was released in Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Dear Sugar (UK; public library), along with several never-before-published columns, under Sugar's real name: Cheryl Strayed.

The book, one of the year's finest reads in psychology and philosophy, is titled after Dear Sugar #64, which remains my own favorite by a long stretch. It's exquisite in its entirety, but this particular bit makes the heart tremble with raw heartness:

Your assumptions about the lives of others are in direct relation to your naïve pomposity. Many people you believe to be rich are not rich. Many people you think have it easy worked hard for what they got. Many people who seem to be gliding right along have suffered and are suffering. Many people who appear to you to be old and stupidly saddled down with kids and cars and houses were once every bit as hip and pompous as you.

Your assumptions about the lives of others are in direct relation to your naïve pomposity. Many people you believe to be rich are not rich. Many people you think have it easy worked hard for what they got. Many people who seem to be gliding right along have suffered and are suffering. Many people who appear to you to be old and stupidly saddled down with kids and cars and houses were once every bit as hip and pompous as you.

When you meet a man in the doorway of a Mexican restaurant who later kisses you while explaining that this kiss doesn't 'mean anything' because, much as he likes you, he is not interested in having a relationship with you or anyone right now, just laugh and kiss him back. Your daughter will have his sense of humor. Your son will have his eyes.

The useless days will add up to something. The shitty waitressing jobs. The hours writing in your journal. The long meandering walks. The hours reading poetry and story collections and novels and dead people's diaries and wondering about sex and God and whether you should shave under your arms or not. These things are your becoming.

One Christmas at the very beginning of your twenties when your mother gives you a warm coat that she saved for months to buy, don't look at her skeptically after she tells you she thought the coat was perfect for you. Don't hold it up and say it's longer than you like your coats to be and too puffy and possibly even too warm. Your mother will be dead by spring. That coat will be the last gift she gave you. You will regret the small thing you didn't say for the rest of your life.

Say thank you.

* * * MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK * * *

HOW TO BE AN EXPLORER OF THE WORLD

HOW TO BE AN EXPLORER OF THE WORLD

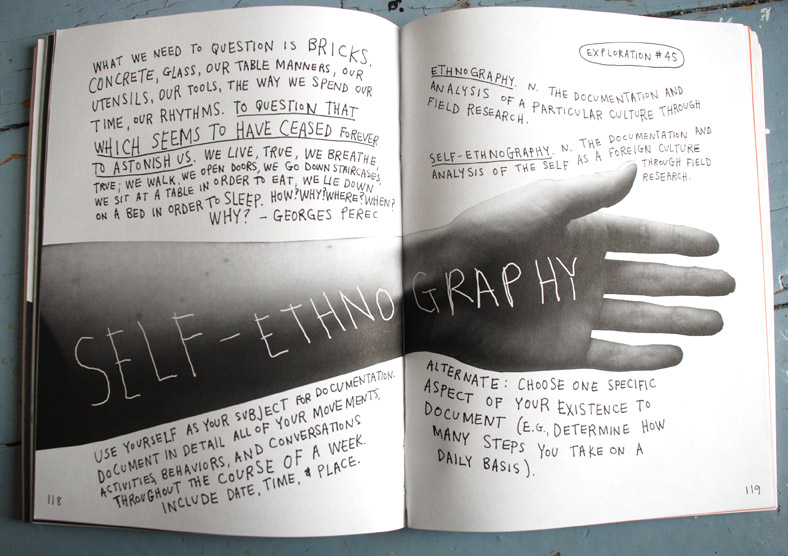

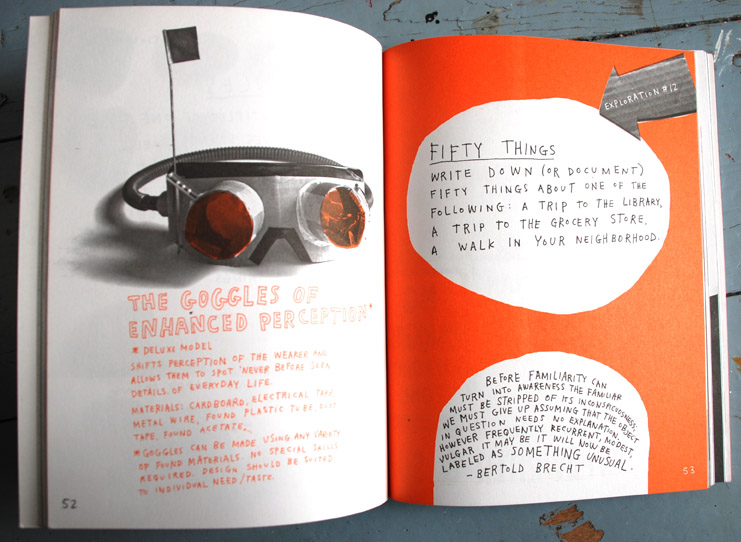

As a longtime fan of guerrilla artist and illustrator Keri Smith's Wreck This Box set of interactive journals, part of these 7 favorite activity books for grown-ups, I was delighted to discover her How to Be an Explorer of the World: Portable Life Museum (UK; public library) – a wonderful compendium of 59 ideas for how to get creatively unstuck by engaging with everyday objects and your surroundings in novel ways. From mapping found sounds to learning the language of trees to turning time observation into art, these playful and poetic micro-projects aren't just a simple creativity booster – they're potent training for what Buddhism would call "living from presence" and inhabiting your life more fully.

As a longtime fan of guerrilla artist and illustrator Keri Smith's Wreck This Box set of interactive journals, part of these 7 favorite activity books for grown-ups, I was delighted to discover her How to Be an Explorer of the World: Portable Life Museum (UK; public library) – a wonderful compendium of 59 ideas for how to get creatively unstuck by engaging with everyday objects and your surroundings in novel ways. From mapping found sounds to learning the language of trees to turning time observation into art, these playful and poetic micro-projects aren't just a simple creativity booster – they're potent training for what Buddhism would call "living from presence" and inhabiting your life more fully.

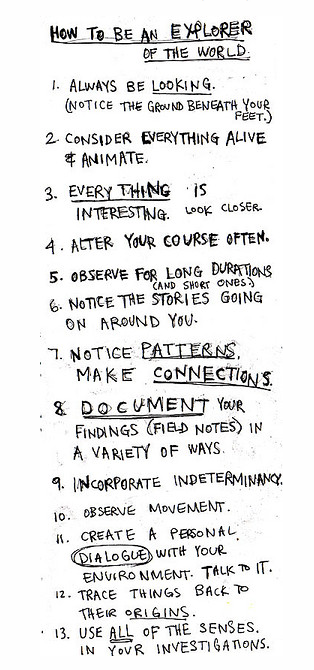

It all began with this simple list, which Smith scribbled on a piece of paper in the middle a sleepless night in 2007:

Eventually, it became the book.

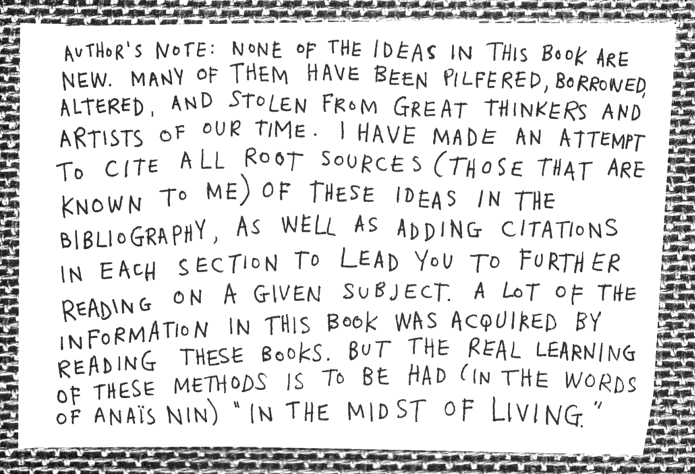

Especially delightful – and not only because of the Anaïs Nin reference – is this author's note in the preface, a nod to Mark Twain's conviction that "all ideas are second-hand" and Henry Miller's contention that most of what we create is composed of "hand-me-down ideas":

* * * MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK * * *

STEAL LIKE AN ARTIST

STEAL LIKE AN ARTIST

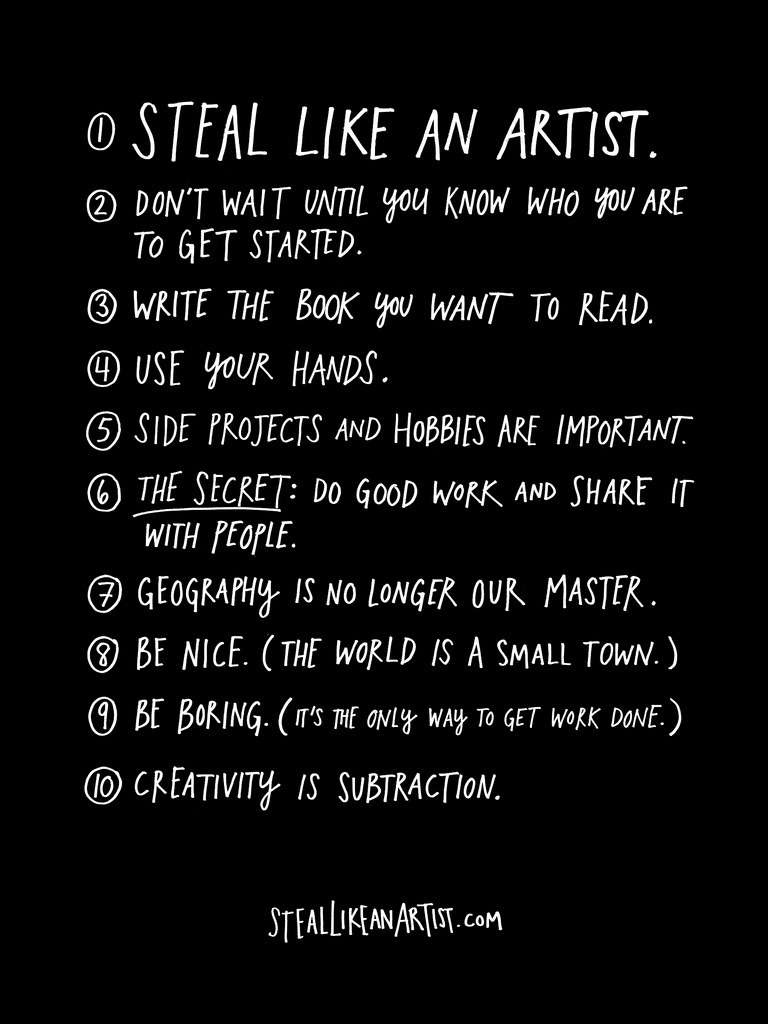

Much has been said about how creativity works, what its secrets are, and where good ideas come from, but most of that wisdom can be lost on young minds just dipping their toes in the vast and tumultuous ocean of self-initiated creation. Some time ago, artist and writer Austin Kleon – one of my favorite thinkers, a keen observer of and participant in the creative economy of the digital age – was invited to give a talk to students, the backbone for which was a list of 10 things he wished he'd heard as a young creator:

Much has been said about how creativity works, what its secrets are, and where good ideas come from, but most of that wisdom can be lost on young minds just dipping their toes in the vast and tumultuous ocean of self-initiated creation. Some time ago, artist and writer Austin Kleon – one of my favorite thinkers, a keen observer of and participant in the creative economy of the digital age – was invited to give a talk to students, the backbone for which was a list of 10 things he wished he'd heard as a young creator:

So widely did the talk resonate that Kleon decided to deepen and enrich its message in Steal Like an Artist (UK; public library), one of the best art books of 2012 – an intelligent and articulate manifesto for the era of combinatorial creativity and remix culture that's part 344 Questions, part Everything is a Remix, part The Gift, at once borrowed and entirely original.

The book opens with a timeless T.S. Eliot endorsement of remix culture:

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.

Kleon goes on to delineate the qualities you'll need to cultivate for the creative life – things like kindness, curiosity, "productive procrastination," "a willingness to look stupid" – demonstrating that "creativity" isn't some abstract phenomenon bestowed upon the fortunate few but, rather, a deliberate mindset and pragmatic ethos we can architect for ourselves. As he puts it, "you are a mashup of what you let into your life."

He writes in the introduction:

It's one of my theories that when people give advice, they're really just talking to themselves in the past.

It's one of my theories that when people give advice, they're really just talking to themselves in the past.

This book is me talking to a previous version of myself.

These are things I've learned over almost a decade of trying to figure out how to make art, but a funny thing happened when I started sharing them with others – I realized that they aren't just for artists. They're for everyone.

These ideas are for everyone who's trying to inject some creativity into their life and their work. (That should describe all of us.)

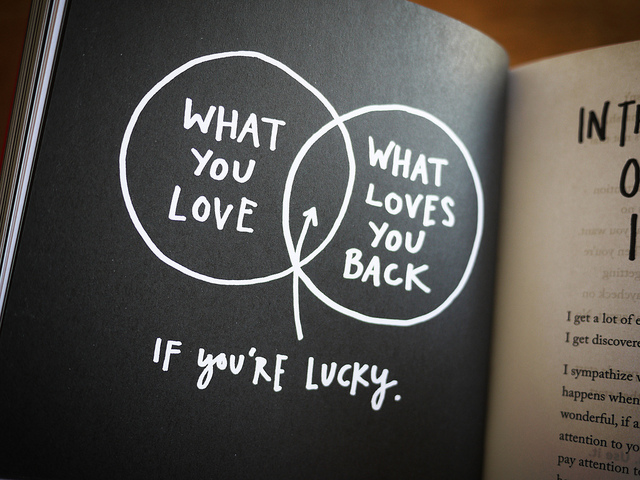

On doing what you love, Kleon urges:

Draw the art you want to see, start the business you want to run, play the music you want to hear, write the books you want to read, build the products you want to use – do the work you want to see done.

Draw the art you want to see, start the business you want to run, play the music you want to hear, write the books you want to read, build the products you want to use – do the work you want to see done.

* * * MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK * * *

A TECHNIQUE FOR PRODUCING IDEAS

A TECHNIQUE FOR PRODUCING IDEAS

Literature is the original "inter-net," woven of a web of allusions, references, and citations that link different works together into an endless rabbit hole of discovery. Case in point: Last week's wonderful field guide to creativity, Dancing About Architecture, mentioned in passing an intriguing old book originally published by James Webb Young in 1939 – A Technique for Producing Ideas (UK; public library), which I promptly hunted down and which will be the best $5 you spend this year, or the most justified trip to your public library.

Literature is the original "inter-net," woven of a web of allusions, references, and citations that link different works together into an endless rabbit hole of discovery. Case in point: Last week's wonderful field guide to creativity, Dancing About Architecture, mentioned in passing an intriguing old book originally published by James Webb Young in 1939 – A Technique for Producing Ideas (UK; public library), which I promptly hunted down and which will be the best $5 you spend this year, or the most justified trip to your public library.

Young – an ad man by trade but, as we'll see, a voraciously curious and cross-disciplinary thinker at heart – lays out with striking lucidity and clarity the five essential steps for a productive creative process, touching on a number of elements corroborated by modern science and thinking on creativity: its reliance on process over mystical talent, its combinatorial nature, its demand for a pondering period, its dependence on the brain's unconscious processes, and more.

Right from the introduction, original Mad Man and DDB founder Bill Bernbach captures the essence of Young's ideas, with which Steve Jobs would have no doubt agreed when he proclaimed that "creativity is just connecting things":

Mr. Young is in the tradition of some of our greatest thinkers when he describes the workings of the creative process. It is a tribute to him that such scientific giants as Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein have written similarly on this subject. They agree that knowledge is basic to good creative thinking but that it is not enough, that this knowledge must be digested and eventually emerge in the form of fresh, new combinations and relationships. Einstein refers to this as intuition, which he considers the only path to new insights.

Mr. Young is in the tradition of some of our greatest thinkers when he describes the workings of the creative process. It is a tribute to him that such scientific giants as Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein have written similarly on this subject. They agree that knowledge is basic to good creative thinking but that it is not enough, that this knowledge must be digested and eventually emerge in the form of fresh, new combinations and relationships. Einstein refers to this as intuition, which he considers the only path to new insights.

To be sure, however, Young marries the intuitive with the practical in his formulation:

[T]he production of ideas is just as definite a process as the production of Fords; that the production of ideas, too, runs on an assembly line; that in this production the mind follows an operative technique which can be learned and controlled; and that its effective use is just as much a matter of practice in the technique as is the effective use of any tool.

[T]he production of ideas is just as definite a process as the production of Fords; that the production of ideas, too, runs on an assembly line; that in this production the mind follows an operative technique which can be learned and controlled; and that its effective use is just as much a matter of practice in the technique as is the effective use of any tool.

In a chapter on training the mind, Young offers:

In learning any art the important things to learn are, first, Principles, and second, Method. This is true of the art of producing ideas.

In learning any art the important things to learn are, first, Principles, and second, Method. This is true of the art of producing ideas.

Particular bits of knowledge are nothing, because they are made up [of] so called rapidly aging facts. Principles and method are everything. … So with the art of producing ideas. What is most valuable to know is not where to look for a particular idea, but how to train the mind in the method by which all ideas are produced and how to grasp the principles which are at the source of all ideas.

But the most compelling part of Young's treatise, in a true embodiment of combinatorial creativity, builds upon the work of legendary Italian sociologist Vilfredo Pareto (of Pareto principle fame) and his The Mind and Society. Young proposes two key principles for creating – that an idea is a new combination and that the ability to generate new combinations depends on the ability to see relationships between different elements.

The first [principle is] that an idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements. … The second important principle involved is that the capacity to bring old elements into new combinations depends largely on the ability to see relationships. Here, I suspect, is where minds differ to the greatest degree when it comes to the production of ideas. To some minds each fact is a separate bit of knowledge. To others it is a link in a chain of knowledge. It has relationships and similarities. It is not so much a fact as it is an illustration of a general law applying to a whole series of facts. … Consequently the habit of mind which leads to a search for relationships between facts becomes of the highest importance in the production of ideas.

The first [principle is] that an idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements. … The second important principle involved is that the capacity to bring old elements into new combinations depends largely on the ability to see relationships. Here, I suspect, is where minds differ to the greatest degree when it comes to the production of ideas. To some minds each fact is a separate bit of knowledge. To others it is a link in a chain of knowledge. It has relationships and similarities. It is not so much a fact as it is an illustration of a general law applying to a whole series of facts. … Consequently the habit of mind which leads to a search for relationships between facts becomes of the highest importance in the production of ideas.

* * * SEE THE 5-STEP TECHNIQUE * * *

100 IDEAS THAT CHANGED GRAPHIC DESIGN

100 IDEAS THAT CHANGED GRAPHIC DESIGN

Design history books abound, but they tend to be organized by chronology and focused on concrete -isms. From publisher Laurence King, who brought us the epic Saul Bass monograph, and the prolific design writer Steven Heller with design critic Veronique Vienne comes 100 Ideas that Changed Graphic Design (UK; public library) – a thoughtfully curated inventory of abstract concepts that defined and shaped the art and craft of graphic design, each illustrated with exemplary images and historical context, and one of the year's best design books.

Design history books abound, but they tend to be organized by chronology and focused on concrete -isms. From publisher Laurence King, who brought us the epic Saul Bass monograph, and the prolific design writer Steven Heller with design critic Veronique Vienne comes 100 Ideas that Changed Graphic Design (UK; public library) – a thoughtfully curated inventory of abstract concepts that defined and shaped the art and craft of graphic design, each illustrated with exemplary images and historical context, and one of the year's best design books.

From concepts like manifestos (#25), pictograms (#45), propaganda (#22), found typography (#38), and the Dieter-Rams-coined philosophy that "less is more" (#73) to favorite creators like Alex Steinweiss, Noma Bar, Saul Bass, Paula Scher, and Stefan Sagmeister, the sum of these carefully constructed parts amounts to an astute lens not only on what design is and does, but also on what it should be and do.

Idea # 16: METAPHORIC LETTERING :: Trying to Look Good Limits My Life (2004), part of Stefan Sagmeister’s typographic project '20 Things I Have Learned in My Life So Far.' Words are formed from natural and industrial materials and composed in situ.

Heller and Vienne write in the introduction:

[Big ideas] are notions, conceptions, inventions, and inspirations – formal, pragmatic, and conceptual – that have been employed by graphic designers to enhance all genres of visual communication. These ideas have become, through synthesis and continual application, the ambient language(s) of graphic design. They constitute the technological, philosophical, forma, and aesthetic constructs of graphic design.

[Big ideas] are notions, conceptions, inventions, and inspirations – formal, pragmatic, and conceptual – that have been employed by graphic designers to enhance all genres of visual communication. These ideas have become, through synthesis and continual application, the ambient language(s) of graphic design. They constitute the technological, philosophical, forma, and aesthetic constructs of graphic design.

Idea # 19: VISUAL PUNS :: Gun Crime (2010), illustrated by Noma Bar, is a commentary on the tragic toll of gun-related violence in the UK. The trigger serves as the mechanism and outcome of gun attacks.

From how rub-on lettering democratized design by fueling the DIY movement and engaging people who knew nothing about typography to how the concept of the "teenager" was invented after World War II as a new market for advertisers, many of the ideas are mother-of-invention parables. Together, they converge into a cohesive meditation on the fundamental mechanism of graphic design – to draw a narrative with a point of view, and then construct that narrative through the design process and experience.

Idea # 37: DUST JACKETS :: Ulysses (1934), hand-lettered and designed by Ernst Reichl, was said to be influenced by the paintings of Piet Mondrian.

On a recent episode of Debbie Millman's invariably excellent Design Matters podcast, Heller talks about the process and rationale behind 100 Ideas that Changed Graphic Design:

History, as we all know, is written by the survivors. And there are certain historical facts that never get covered. And, in graphic design, it's fascinating how many things don't get covered until somebody uncovers them.

History, as we all know, is written by the survivors. And there are certain historical facts that never get covered. And, in graphic design, it's fascinating how many things don't get covered until somebody uncovers them.

Also from the series: 100 Ideas That Changed Art, 100 Ideas That Changed Film, 100 Ideas That Changed Architecture, and 100 Ideas That Changed Photography.

* * * MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK * * *

THE WHERE, THE WHY, AND THE HOW

THE WHERE, THE WHY, AND THE HOW

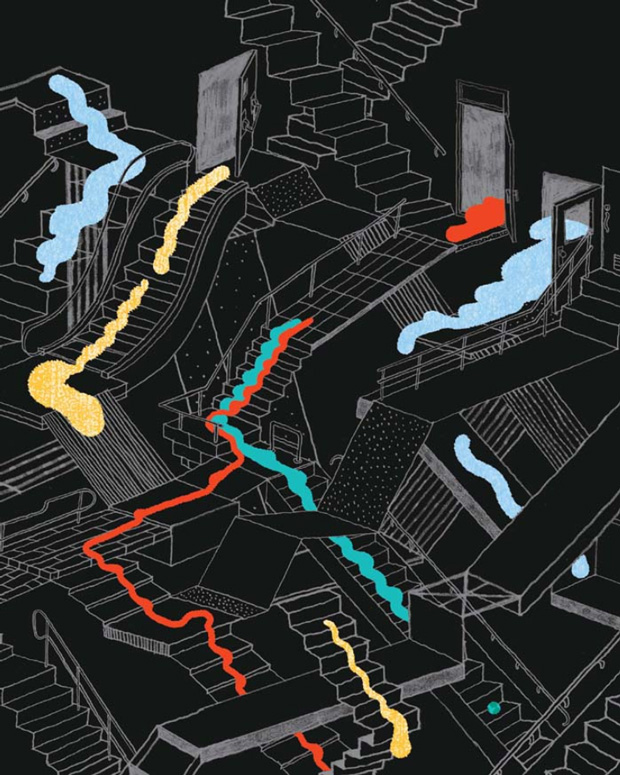

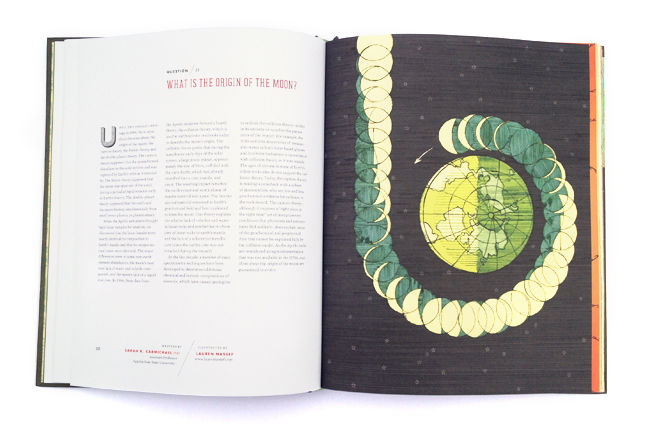

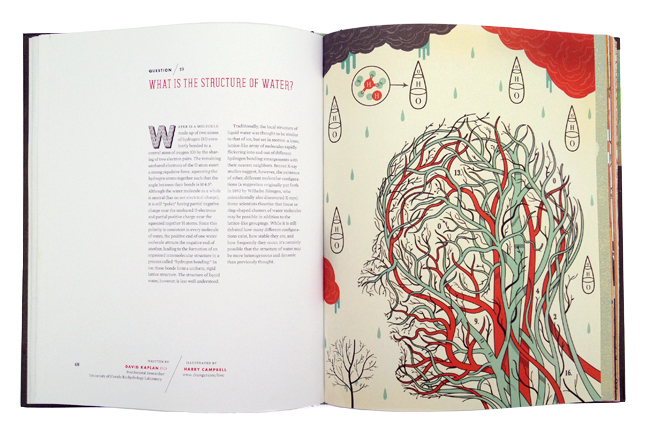

At the intersection of art and science, The Where, the Why, and the How: 75 Artists Illustrate Wondrous Mysteries of Science (UK; public library), one of the year's best science books, invites some of today's most celebrated artists to create scientific illustrations and charts to accompany short essays about the most fascinating unanswered questions on the minds of contemporary scientists across biology, astrophysics, chemistry, quantum mechanics, anthropology, and more. The questions cover such mind-bending subjects as whether there are more than three dimensions, why we sleep and dream, what causes depression, how long trees live, and why humans are capable of language.

At the intersection of art and science, The Where, the Why, and the How: 75 Artists Illustrate Wondrous Mysteries of Science (UK; public library), one of the year's best science books, invites some of today's most celebrated artists to create scientific illustrations and charts to accompany short essays about the most fascinating unanswered questions on the minds of contemporary scientists across biology, astrophysics, chemistry, quantum mechanics, anthropology, and more. The questions cover such mind-bending subjects as whether there are more than three dimensions, why we sleep and dream, what causes depression, how long trees live, and why humans are capable of language.

The images, which come from a mix of well-known titans and promising up-and-comers, including favorites like Lisa Congdon, Gemma Correll, and Jon Klassen, borrow inspiration from antique medical illustrations, vintage science diagrams, and other historical ephemera from periods of explosive scientific curiosity.

Above all, the project is a testament to the idea that ignorance is what drives discovery and wonder is what propels science – a reminder to, as Rilke put it, live the questions and delight in reflecting on the mysteries themselves. The trio urge in the introduction:

With this book, we wanted to bring back a sense of the unknown that has been lost in the age of information. ... Remember that before you do a quick online search for the purpose of the horned owl's horns, you should give yourself some time to wonder.

With this book, we wanted to bring back a sense of the unknown that has been lost in the age of information. ... Remember that before you do a quick online search for the purpose of the horned owl's horns, you should give yourself some time to wonder.

Pondering the age-old question of why the universe exists, Brian Yanny asks:

Was there an era before our own, out of which our current universe was born? Do the laws of physics, the dimensions of space-time, the strengths and types and asymmetries of nature's forces and particles, and the potential for life have to be as we observe them, or is there a branching multi-verse of earlier and later epochs filled with unimaginably exotic realms? We do not know.

Was there an era before our own, out of which our current universe was born? Do the laws of physics, the dimensions of space-time, the strengths and types and asymmetries of nature's forces and particles, and the potential for life have to be as we observe them, or is there a branching multi-verse of earlier and later epochs filled with unimaginably exotic realms? We do not know.

What existed before the big bang? :: Illustrated by Josh Cochran

Zooming in on the microcosm of our own bodies and their curious behaviors, Jill Conte considers why we blush:

The ruddy or darkened hue of a blush occurs when muscles in the walls of blood vessels within the skin relax and allow more blood to flow. Interestingly, the skin of the blush region contains more blood vessels than do other parts of the body. These vessels are also larger and closer to the surface, which indicates a possible relationship among physiology, emotion, and social communication. While it is known that blood flow to the skin, which serves to feed cells and regulate surface body temperature, is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, the exact mechanism by which this process is activated specifically to produce a blush remains unknown.

The ruddy or darkened hue of a blush occurs when muscles in the walls of blood vessels within the skin relax and allow more blood to flow. Interestingly, the skin of the blush region contains more blood vessels than do other parts of the body. These vessels are also larger and closer to the surface, which indicates a possible relationship among physiology, emotion, and social communication. While it is known that blood flow to the skin, which serves to feed cells and regulate surface body temperature, is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, the exact mechanism by which this process is activated specifically to produce a blush remains unknown.

* * * MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK * * *

* * * SEE NUMBERS 8-9 * * *

WHAT'S A DOG FOR

WHAT'S A DOG FOR

It must be the season of the dog, from the recent treasure chest that is The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs (one of the the best art books of 2012) to the history of rabies to Fiona Apple's stirring handwritten letter about her dying dog. But what is it about dogs, exactly, that has us so profoundly transfixed?

It must be the season of the dog, from the recent treasure chest that is The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs (one of the the best art books of 2012) to the history of rabies to Fiona Apple's stirring handwritten letter about her dying dog. But what is it about dogs, exactly, that has us so profoundly transfixed?

That's exactly what former New York magazine executive editor John Homans explores in What's a Dog For?: The Surprising History, Science, Philosophy, and Politics of Man's Best Friend (public library) – a remarkable chronicle of the domestic dog's journey across thousands of years and straight into our hearts, written with equal parts tenderness and scientific rigor.

In a chapter on reconciling the inevitable pain we invite into our lives when we commit to love a being biologically destined to die before we do and the boundless joy of choosing to love anyway, Homans cites John Updike's heartbreaking poem "Another Dog's Death" about the last days of one of his beloved animals. But rather than agonizing over the morbidity of it, Homans celebrates the remarkable Zen-ness of it all, somewhere between John Cage and the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi:

This state of being-in-the-moment is what's so compelling about dogs. It's hard for a human to get to it. Even in the most difficult times, dogs are cheerful and ready for experience. A dog can't figure out that it's being measured for its grave. The three-legged chow that walks on my street every day doesn't know the number three or have any sense that anything is wrong with her at all (and as I write, the dog is sixteen and still fit). It's not that a dog accepts the cards it's been dealt; it's not aware that there are cards. James Thurber called the desire for this condition 'the Dog Wish,' the 'strange and involved compulsion to be as happy and carefree as a dog.' This is a dog's blessing, a dim-wittedness one can envy.

This state of being-in-the-moment is what's so compelling about dogs. It's hard for a human to get to it. Even in the most difficult times, dogs are cheerful and ready for experience. A dog can't figure out that it's being measured for its grave. The three-legged chow that walks on my street every day doesn't know the number three or have any sense that anything is wrong with her at all (and as I write, the dog is sixteen and still fit). It's not that a dog accepts the cards it's been dealt; it's not aware that there are cards. James Thurber called the desire for this condition 'the Dog Wish,' the 'strange and involved compulsion to be as happy and carefree as a dog.' This is a dog's blessing, a dim-wittedness one can envy.

He considers the warm tackiness of loving a dog:

Loving a dog means, among other things, making peace with kitsch, if you haven't already. You don't have to make goo-goo eyes at every puppy picture you see in a magazine or bake your dog birthday cakes. But if you resist too much the power of the big primary-color emotions that surround the dog, you're missing the experience. … Dogs are a national religion with a catechism composed by Hallmark, so heresy is necessary. I suspect some people resist the dog culture with such passion precisely to avoid the kitsch, the appalling melodrama: if you give in to it, you're trapped in a narrative you can't control. You feel like a dope, buying into it. The emotions around the dog can be as neotenized as the animal itself.

Rather than an end, kitsch can be a starting point. … Much as I'd like to think that kitsch has no purchase in my world, it's found its way in – and it's sleeping on my rug.

Loving a dog means, among other things, making peace with kitsch, if you haven't already. You don't have to make goo-goo eyes at every puppy picture you see in a magazine or bake your dog birthday cakes. But if you resist too much the power of the big primary-color emotions that surround the dog, you're missing the experience. … Dogs are a national religion with a catechism composed by Hallmark, so heresy is necessary. I suspect some people resist the dog culture with such passion precisely to avoid the kitsch, the appalling melodrama: if you give in to it, you're trapped in a narrative you can't control. You feel like a dope, buying into it. The emotions around the dog can be as neotenized as the animal itself.

Rather than an end, kitsch can be a starting point. … Much as I'd like to think that kitsch has no purchase in my world, it's found its way in – and it's sleeping on my rug.

Beautifully written and absolutely engrossing, What's a Dog For? goes on to examine such fascinating fringes of canine culture as how dogs served as Darwin's muse, why they were instrumental in the birth of empathy, and what they might reveal about the future of evolution.

* * * MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK * * *

* * * SEE FULL LIST * * *